Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Paraneoplastic syndromes are symptoms that occur at sites distant from a tumor or its metastasis. They are rare disorders that are triggered by an altered immune system response to a neoplasm.

Recent medical advances have improved the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of paraneoplastic syndromes. These disorders arise from tumor secretion of hormones, peptides, or cytokines or immune cross-reactivity between malignant and normal tissues.

Paraneoplastic syndromes may affect diverse organ systems, most notably the endocrine, neurologic, dermatologic, rheumatologic, and hematologic systems.

Up to 20% of cancer patients experience paraneoplastic syndromes, but often these syndromes are unrecognized. In some instances, the timely diagnosis of these conditions may lead to the detection of an otherwise clinically occult tumor at an early and highly treatable stage.

Because paraneoplastic syndromes often cause considerable morbidity, effective treatment can improve patient quality of life, enhance the delivery of cancer therapy, and prolong survival.

The most common cancers associated with paraneoplastic syndromes include:

- Lung carcinoma, especially small cell lung cancer (most common)

- Renal carcinoma

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Leukemias

- Lymphomas

- Breast tumors

- Ovarian tumors

- Neural cancers

- Gastric cancers

- Pancreatic cancers

Successful treatment is best obtained by controlling underlying cancer, but some symptoms can be controlled with specific drugs (eg, cyproheptadine or somatostatin analogues for carcinoid syndrome, bisphosphonates and corticosteroids for hypercalcemia).

General paraneoplastic symptoms:

Patients with cancer often experience fever, night sweats, anorexia, and cachexia. These symptoms may arise from the release of cytokines involved in the inflammatory or immune response or from mediators involved in tumor cell death, such as tumor necrosis factor-αlpha. Alterations in liver function and steroidogenesis may also contribute.

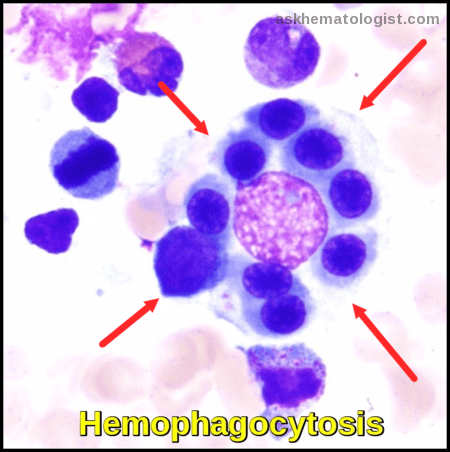

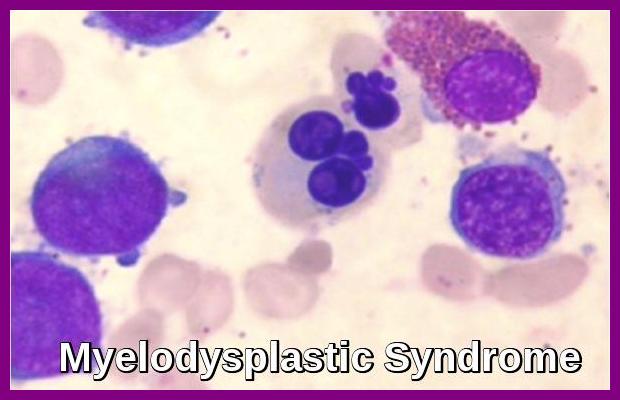

Hematologic paraneoplastic syndromes:

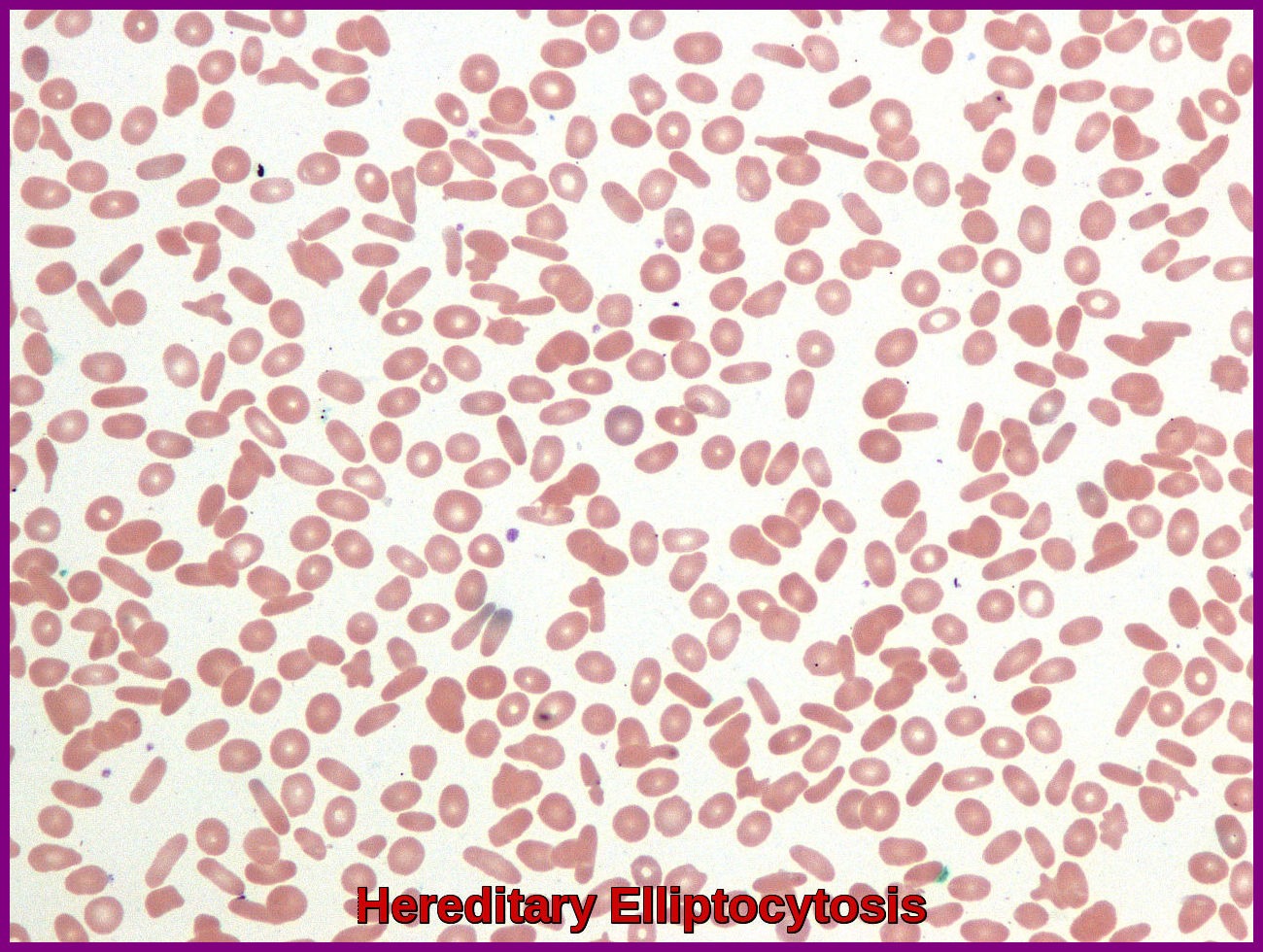

Patients with cancer may develop pure RBC aplasia, anemia of chronic disease, leukocytosis (leukemoid reaction), thrombocytosis, eosinophilia, basophilia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

In addition, immune thrombocytopenia and a Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia can complicate the course of lymphoid cancers and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Erythrocytosis may occur in various cancers, especially renal cancers and hepatomas, due to ectopic production of erythropoietin or erythropoietin-like substances, and monoclonal gammopathies may sometimes be present.

Demonstrated mechanisms of hematologic abnormalities include tumor-generated substances that mimic or block normal endocrine signals for hematologic line development and generation of antibodies that cross-react with receptors or cell lines.

Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes:

Skin changes can often be the first sign of a deeper problem including an internal malignancy. Signs of skin disease may precede, occur with, or follow the detection of an associated cancer. These skin diseases can be a feature of an undiagnosed cancer and may be the prompt for a thorough examination in patients. Or in a patient whose cancer is in remission, these skin diseases may be the initial sign of the cancer recurring.

Patients may experience many skin symptoms.

Itching is the most common cutaneous symptom experienced by patients with cancer (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma) and may result from hypereosinophilia.

Flushing may also occur and is likely related to tumor-generated circulating vasoactive substances (e.g., prostaglandins).

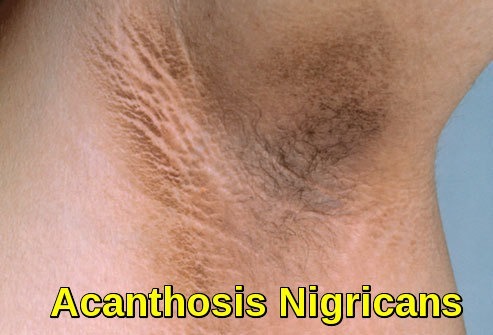

Pigmented skin lesions, or keratoses, may appear, including acanthosis nigricans (GI cancer), generalized dermic melanosis (lymphoma, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma), Bowen disease (lung, GI, GU cancer), and large multiple seborrheic keratoses, ie, Leser-Trélat signs (lymphoma, GI cancer).

Pigmented skin lesions, or keratoses, may appear, including acanthosis nigricans (GI cancer), generalized dermic melanosis (lymphoma, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma), Bowen disease (lung, GI, GU cancer), and large multiple seborrheic keratoses, ie, Leser-Trélat signs (lymphoma, GI cancer).

Herpes zoster may result from reactivation of latent virus in patients with immune system depression or dysfunction.

Acquired ichthyosis, dermatomyositis and paraneoplastic pemphigus could be also cutaneous manifestations of occult malignancy.

Dermatomyositis presenting as a paraneoplastic syndrome due to underlying breast cancer | BMJ Case Reports

Paraneoplastic endocrine syndromes:

Paraneoplastic endocrine syndromes result from the ectopic production of hormones by different tumors.

Hypercalcemia of malignancy is the most common, mostly caused

by ectopic parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) production from squamous cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, bladder cancer which increases bone resorption. Other causes include the rare ectopic parathyroid hormone (PTH) production, ectopic production of 1, 25-(OH)2 vitamin D by the tumor and its adjacent macrophages and bone metastasis which by itself in addition to the local production of PTHrP at the level of the bone lead to bone resorption and thus hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia symptoms include polyuria, dehydration, constipation, and muscle weakness. Treatment includes extracellular fluid volume repletion, bisphosphonates or denosumab and calcitonin.

Ectopic Cushing’s syndrome caused by ectopic ACTH production or ACTH-like molecules, most often with small cell cancer of the lung results in hypokalemia, proximal muscle weakness, easy bruisability, central obesity, moon facies, hypertension, diabetes and psychiatric abnormalities including depression and mood disorders. Different diagnostic measures help to differentiate Cushing’s disease from ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Treatment includes surgical resection of tumor and medical therapy to suppress excess cortisol production.

Ectopic secretion of ADH causes abnormalities in water and electrolyte balance, including hyponatremia, most often from small cell and non–small cell lung cancer. The best treatment options include removal of the underlying tumor, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy in addition to free water restriction, demeclocycline and vaptans.

Ectopic growth hormone-releasing hormone secretion has been identified with carcinoids, pheochromocytoma and other tumors. Surgery is the mainstay of therapy with systemic therapy used in metastatic disease.

Hypoglycemia may result from the production of insulin-like growth factors or insulin production by pancreatic islet cell tumors or hemangiopericytomas.

Refractory hyperglycemia may be due to glucagon-producing pancreatic tumors.

Hypertension may result from abnormal epinephrine and norepinephrine secretion (pheochromocytomas) or from cortisol excess (ACTH-secreting tumors).

Ectopic calcitonin production (from breast cancer, small cell lung cancer, and medullary thyroid carcinoma) causes a fall in the serum Ca level, leading to muscle twitching and cardiac arrhythmias.

Other rare ectopic hormone syndromes have also been identified including

ectopic prolactin, ectopic erythropoietin, ectopic thyroid-stimulating hormone (from gestational choriocarcinoma), and thrombopoietin in addition to others.

Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes:

Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes (PNS) are a group of conditions that affect the nervous system (brain, spinal cord, nerves and/or muscles) in patients with cancer.

The term “paraneoplastic” means that the neurological syndrome is not caused by the tumor itself, but by the immunological reactions that the tumor produces.

It is believed that the body’s normal immunological system interprets the tumor as an invasion. When this occurs, the immunological system mounts an immune response, utilizing antibodies and lymphocytes to fight the tumor. The end result is that the patient’s own immune system can cause collateral damage to the nervous system, which can sometimes be severe. In many patients, the immune response can cause nervous system damage that far exceeds the damage done to the tumor.

The effects of PNS can remit entirely, although there can also be permanent effects.

Several types of peripheral neuropathy are among the neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes. Cerebellar syndromes and other central neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes also occur.

Peripheral neuropathy is the most common neurologic paraneoplastic syndrome. It is usually a distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy that causes mild motor weakness, sensory loss, and absent distal reflexes. The syndrome is indistinguishable from that accompanying many chronic illnesses.

Subacute sensory neuropathy is a more specific but rare peripheral neuropathy. Dorsal root ganglia degeneration and progressive sensory loss with ataxia but little motor weakness develop; the disorder may be disabling. Anti-Hu, an autoantibody, is found in the serum of some patients with lung cancer. There is no treatment.

Guillain-Barré syndrome, another ascending peripheral neuropathy, is a rare finding in the general population and probably more common in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Eaton-Lambert syndrome is an immune-mediated, myasthenia-like syndrome with weakness usually affecting the limbs and sparing ocular and bulbar muscles. It is presynaptic, resulting from the impaired release of acetylcholine from nerve terminals. An IgG antibody is involved. The syndrome can precede, occur with, or develop after the diagnosis of cancer. It occurs most commonly in men with intrathoracic tumors (70% have small or oat cell lung carcinoma). Symptoms and signs include fatigability, weakness, pain in proximal limb muscles, peripheral paresthesias, dry mouth, erectile dysfunction, and ptosis. Deep tendon reflexes are reduced or lost. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding an incremental response to repetitive nerve stimulation: Amplitude of the compound muscle action potential increases > 200% at rates > 10 Hz. Treatment is first directed at the underlying cancer and sometimes induces remission. Guanidine (initially 125 mg po qid, gradually increased to a maximum of 35 mg/kg), which facilitates acetylcholine release, often lessens symptoms but may depress bone marrow and liver function. Corticosteroids and plasma exchange benefit some patients.

Subacute cerebellar degeneration causes progressive bilateral leg and arm ataxia, dysarthria, and sometimes vertigo and diplopia. Neurologic signs may include dementia with or without brain stem signs, ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, and extensor plantar signs, with prominent dysarthria and arm involvement. Cerebellar degeneration usually progresses over weeks to months, often causing profound disability. Cerebellar degeneration may precede the discovery of the cancer by weeks to years. Anti-Yo, a circulating autoantibody, is found in the serum or CSF of some patients, especially women with breast or ovarian cancer. MRI or CT may show cerebellar atrophy, especially late in the disease. Characteristic pathologic changes include widespread loss of Purkinje cells and lymphocytic cuffing of deep blood vessels. CSF occasionally has mild lymphocytic pleocytosis. Treatment is nonspecific, but some improvement may follow successful cancer therapy.

Opsoclonus (spontaneous chaotic eye movements) is a rare cerebellar syndrome that may accompany childhood neuroblastoma. It is associated with cerebellar ataxia and myoclonus of the trunk and extremities. Anti-Ri, a circulating autoantibody, may be present. The syndrome often responds to corticosteroids and treatment of the cancer.

Subacute motor neuronopathy is a rare disorder causing painless lower motor neuron weakness of upper and lower extremities, usually in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma or other lymphomas. Anterior horn cells degenerate. Spontaneous improvement usually occurs.

Subacute necrotizing myelopathy is a rare syndrome in which rapid ascending sensory and motor loss occurs in gray and white matter of the spinal cord, leading to paraplegia. MRI helps rule out epidural compression from metastatic tumor—a much more common cause of rapidly progressive spinal cord dysfunction in patients with cancer. MRI may show necrosis in the spinal cord.

Encephalitis may occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome, taking several different forms, depending on the area of the brain involved. Global encephalitis has been proposed to explain the encephalopathy that occurs most commonly in small cell lung cancer. Limbic encephalitis is characterized by anxiety and depression, leading to memory loss, agitation, confusion, hallucinations, and behavioral abnormalities. Anti-Hu antibodies, directed against RNA binding proteins, may be present in the serum and spinal fluid. MRI may disclose areas of increased contrast uptake and edema.

Anti-Yo Syndrome: Seen in gynecological cancers, this syndrome manifests as cerebellar degeneration, leading to ataxia and other neurological deficits.

Stiff Person Syndrome: This rare disorder involves muscle stiffness and spasms and is often associated with breast cancer. Anti-amphiphysin antibodies may be present.

GI paraneoplastic syndromes:

Watery diarrhea with subsequent dehydration and electrolyte imbalances may result from tumor-related secretion of prostaglandins or vasoactive intestinal peptide. Implicated tumors include pancreatic islet cell tumors and others.

Carcinoid tumors produce serotonin degradation products that lead to flushing, diarrhea, and breathing difficulty.

Protein-losing enteropathies may result from tumor mass inflammation, particularly with lymphomas.

Renal paraneoplastic syndrome:

Membranous glomerulonephritis may occur in patients with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and lymphoma as a result of circulating immune complexes.

Secondary amyloidosis may occur with myeloma, lymphomas, or renal cell carcinomas.

Rheumatologic paraneoplastic syndromes:

Rheumatologic disorders mediated by autoimmune reactions can also be a manifestation of paraneoplastic syndromes.

Arthropathies (rheumatic polyarthritis, polymyalgia) or systemic sclerosis may develop in patients with hematologic cancers or with cancers of the colon, pancreas, or prostate. Systemic sclerosis or SLE may also develop in patients with lung and gynecologic cancers.

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy is prominent with certain lung cancers and manifests as painful swelling of the joints (knees, ankles, wrists, elbows, metacarpophalangeal joints) with effusion and sometimes fingertip clubbing.

Dermatomyositis and, to a lesser degree, polymyositis are thought to be more common in patients with cancer, especially in those > 50 years. Typically, proximal muscle weakness is progressive with pathologically demonstrable muscle inflammation and necrosis. A dusky, erythematous butterfly rash with a heliotrope hue may develop on the cheeks with periorbital edema. Corticosteroids may be helpful.

Summary:

Paraneoplastic syndromes are diverse and can manifest in a variety of ways. They are often associated with malignancies such as lung, breast, ovarian, and hematologic cancers. The underlying pathophysiology involves the immune system mistakenly attacking normal tissues in response to tumor-associated antigens. Due to their rarity and diverse clinical presentations, paraneoplastic syndromes pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. A high index of suspicion, coupled with collaborative efforts among medical specialists, is essential for timely diagnosis and management.

References:

Bilynsky BT, Dzhus MB, Litvinyak RI (2015). The conceptual and clinical problems of paraneoplastic syndrome in oncology and internal medicine. Exp Oncol. 2015 Jun. 37 (2):82-8.

Luigi Santacroce, MD; Wafik S El-Deiry, MD, PhD (2017). Paraneoplastic syndromes https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/280744-overview

Bruce A. Chabner, MD (2013). Paraneoplastic Syndromes – Hematology and Oncology – MSD Manual Professional Edition http://www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/hematology-and-oncology/overview-of-cancer/paraneoplastic-syndromes

Höftberger R, Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J. Update on neurological paraneoplastic syndromes. Curr Opin Oncol. 2015 Sep 1.

Ahmadieh H, Arabi A (2015). Endocrine Paraneoplastic Syndromes: A Review. Endocrinol Metab Int J 1(1): 00004. DOI: 10.15406/emij.2015.01.00004.

Metz S (1975). Ectopic Hormones from Tumors. Ann Intern Med 83(1): 117-118.

M. Catalano (2016). Amiloidosi http://medmedicine.it/articoli/anatomia-patologica/amiloidosi

Darnell, R. B. (1996). Onconeural antigens and the paraneoplastic neurologic disorders: at the intersection of cancer, immunity, and the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(10), 4529-4536.

Graus, F., Delattre, J. Y., Antoine, J. C., Dalmau, J., Giometto, B., Grisold, W., … & Posner, J. B. (2004). Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 75(8), 1135-1140.

Anderson, N. E., & Rosenblum, M. K. (2011). Autoimmune neuropathology of the central nervous system. Current Opinion in Neurology, 24(5), 484-490.

Shilpa Manupati and Farazmand Paymaneh. Paraneoplastic pemphigus https://dermnetnz.org/topics/paraneoplastic-pemphigus

Keywords:

what is paraneoplastic syndrome, paraneoplastic syndromes definition, paraneoplastic syndromes examples, paraneoplastic syndromes lung cancer, paraneoplastic syndromes sclc, paraneoplastic syndromes symptoms, paraneoplastic syndromes of the nervous system, paraneoplastic syndromes renal cell carcinoma, paraneoplastic syndromes associated with breast cancer, paraneoplastic syndrome nervous system symptoms, what is paraneoplastic neurological syndrome, what is the most common paraneoplastic syndrome, paraneoplastic syndrome lung cancer life expectancy, paraneoplastic syndrome lung cancer treatment, paraneoplastic syndrome symptoms lung cancer, paraneoplastic syndrome symptoms treatment, paraneoplastic syndrome psychiatric symptoms, paraneoplastic syndrome cardiac symptoms, paraneoplastic syndrome eye symptoms, paraneoplastic syndrome early symptoms, paraneoplastic syndromes meaning, what cancers cause paraneoplastic syndrome, paraneoplastic syndromes in rheumatology, paraneoplastic syndromes skin.