Hemolytic Anemias

Introduction:

Red blood cells (RBCs) are made in the bone marrow—a sponge-like tissue inside the bones. They live for about 120 days in the bloodstream and then die. Hemolysis involves premature destruction and hence a shortened RBCs life span (< 120 days). When RBCs die, the body’s bone marrow makes more blood cells to replace them. However, in hemolytic anemias, the bone marrow can’t make red blood cells fast enough to meet the body’s needs.

Anemia results when bone marrow production can no longer compensate for the shortened RBCs survival; this condition is termed uncompensated hemolytic anemia. If the marrow can compensate, the condition is termed compensated hemolytic anemia.

Clinical features:

- Features of anemia (feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath on exertion or a poor ability to exercise).

- Mild jaundice.

- Variable degrees of splenomegaly.

- Occasional leg ulcers in chronic cases.

- Occasional biliary colic in chronic cases (pigment gallstones).

Aetiology:

The potential causes of hemolysis are enormous.

Many diseases, conditions, and factors can cause the body to destroy its red blood cells. These causes can be inherited or acquired.

Sometimes, the cause of hemolytic anemia isn’t known.

Inherited Hemolytic Anemias:

In inherited hemolytic anemias, the genes that control how red blood cells are made are faulty.

Different types of faulty genes cause different types of inherited hemolytic anemia. However, in each type, the body makes abnormal red blood cells. The problem with the red blood cells may involve the hemoglobin, cell membrane, or enzymes that maintain healthy red blood cells.

The abnormal cells may be fragile and break down while moving through the bloodstream. If this happens, the spleen may remove the cell debris from the bloodstream.

Inherited hemolytic anemias can be due to :

- Defects of red blood cell membrane production (as in hereditary spherocytosis and hereditary elliptocytosis).

- Defects in hemoglobin production (as in thalassemia, sickle-cell disease, and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia).

- Defective red cell metabolism (as in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and pyruvate kinase deficiency).

Acquired Hemolytic Anemias:

In acquired hemolytic anemias, the body makes normal red blood cells. However, a disease, condition, or other factor destroys the cells. Examples of conditions that can destroy the red blood cells include:

- Immune disorders e.g. SLE.

- Infections which may be viral or bacterial e.g. Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Hepatitis, HIV.

- Malignancy e.g. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and other blood cancers.

- Reactions to medicines or blood transfusions. Drugs that can cause immune hemolytic anemia include: Cephalosporins, Dapsone, Levodopa, Levofloxacin, Methyldopa, Nitrofurantoin, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), Penicillin and its derivatives, Quinidine.

- Hypersplenism.

A careful history, examination, and study of the peripheral blood film provide essential clues in most cases.

The Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) = Direct Coombs Test (DCT) to detect the presence of antibody on the red cells (immune hemolysis) is the next step.

In cases of DAT – negative hemolysis with no obvious clues from the history, examination or blood film, an empirical approach to investigations must be adopted, bearing in mind which disorders are relatively common, e.g. G6PD deficiency.

Investigations:

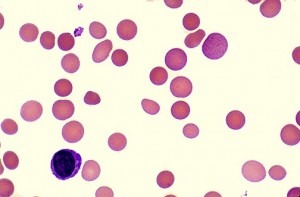

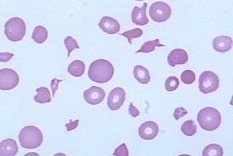

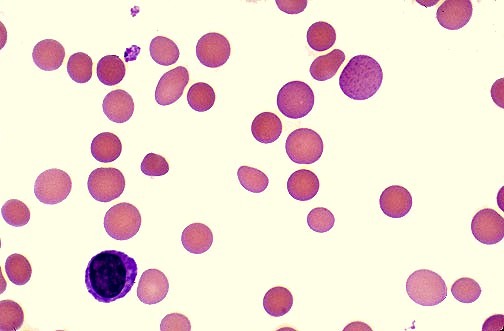

- Blood Smear: evidence of red cell destruction.

- Reduced Hb.

- MCV may be normal or raised.

- Reticulocytosis.

- The blood film may show abnormal red cells, e.g. sickle cells, spherocytes, schistocytes, irregularly contracted cells, nucleated red blood cells (NRBCs).

- Raised serum Hb (intravascular hemolysis).

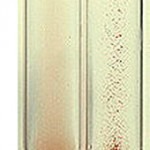

- Hemoglobinuria (intravascular hemolysis) and hemosiderinuria in chronic cases.

- Raised unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin.

- Raised serum LDH.

- Low serum haptoglobin.

- Serum folate could be low.

- Serum Mycoplasma pneumoniae and EBV antibodies (IgM & IgG).

- Hb electrophoresis.

- CXR.

- Abdominal USS.

Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA)

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a relatively uncommon disorder caused by autoantibodies directed against self-red blood cells.

It can be idiopathic or secondary, and classified as warm, cold (cold hemagglutinin disease (CHAD) and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria) or mixed, according to the thermal range of the autoantibody.

AIHA may develop gradually, or have a fulminant onset with life-threatening anemia.

The clinical features, etiology, and investigations are similar to those outlined above.

The first-line therapy for warm AIHA is Corticosteroids, which are effective in 70–85% of patients and should be slowly tapered over a time period of 6–12 months.

Corticosteroids, usually prednisone, are given at the initial dose of 1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day for 1–3 weeks until hemoglobin levels greater than 10 g/dL are reached. Response occurs mainly during the second week, and if none or minimal improvement is observed in the third week, this therapy is assumed to be ineffective. After stabilization of hemoglobin, prednisone should be gradually and slowly tapered off at 10–15 mg weekly to a daily dose of 20–30 mg, then by 5 mg every 1–2 weeks until a dose of 15 mg, and subsequently by 2.5 mg every two weeks with the aim of withdrawing the drug. Although one might be tempted to discontinue steroids more rapidly, AIHA patients should be treated for a minimum of three or four months with low doses of prednisone (≤10 mg/day).

For refractory/relapsed cases, Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen expressed on B cells, has been shown to be effective. Recent reviews reported that rituximab (375 mg/m2 weekly for a median of 4 weeks) is effective in treating both warm AIHA and CHAD, with a median response rate higher in the warm forms. Rituximab has been shown to be effective both in idiopathic and secondary AIHA, including those associated with autoimmune and lymphoproliferative disorders, and bone marrow transplant. In CHAD, rituximab is now recommended as first-line treatment.

Splenectomy is commonly thought to be the most effective conventional third-line treatment of warm AIHA to be proposed to patients unresponsive or intolerant to corticosteroids and Rituximab, in those that require a daily maintenance dose of prednisone greater than 10 mg, and in those with multiple relapses.

Patients who are still refractory or relapsed in spite of the above measures should be considered for immunosuppressive drugs e.g. azathioprine (Imuran), cyclophosphamide, cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil.

Additional therapies are intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), danazol, plasma-exchange, and alemtuzumab as last resort option.

References:

Gehrs BC, Friedberg RC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:258-271.

Hoffman PC. Immune hemolytic anemia – selected topics. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:13-18.

Arndt PA, Garratty G. The changing spectrum of drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:137-144.

What Causes Hemolytic Anemia? – NHLBI, NIH https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ha/causes

Michel M. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Orphanet. August 2010; http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=13392.

Types of Hemolytic Anemia. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). March 21, 2014; http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ha/types.html.