Abnormal Hemoglobins

Abnormal hemoglobins are also known as Hemoglobinopathy, Hemoglobin Variants, Hemoglobin S, Sickle Cell Disease, Hemoglobin C Disease, Hemoglobin E Disease, Thalassemia, Hemoglobin Barts, Hereditary Persistence of Fetal Hemoglobin HPFH.

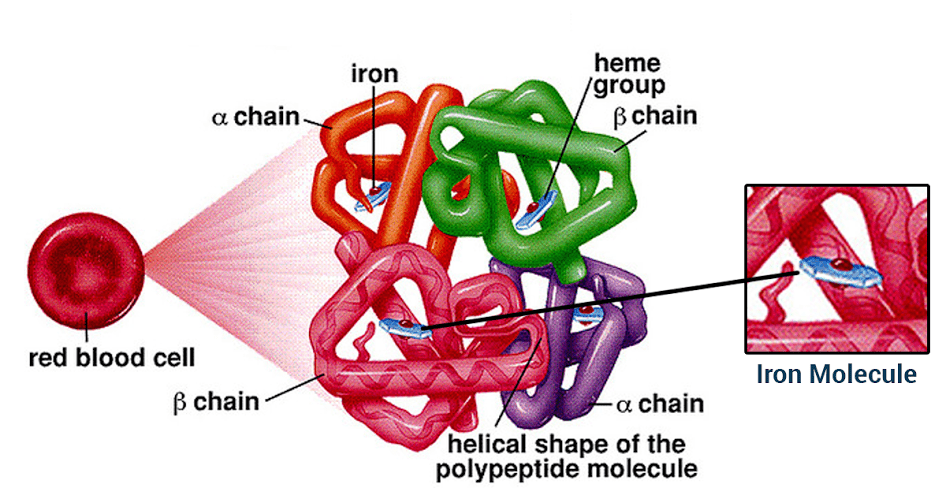

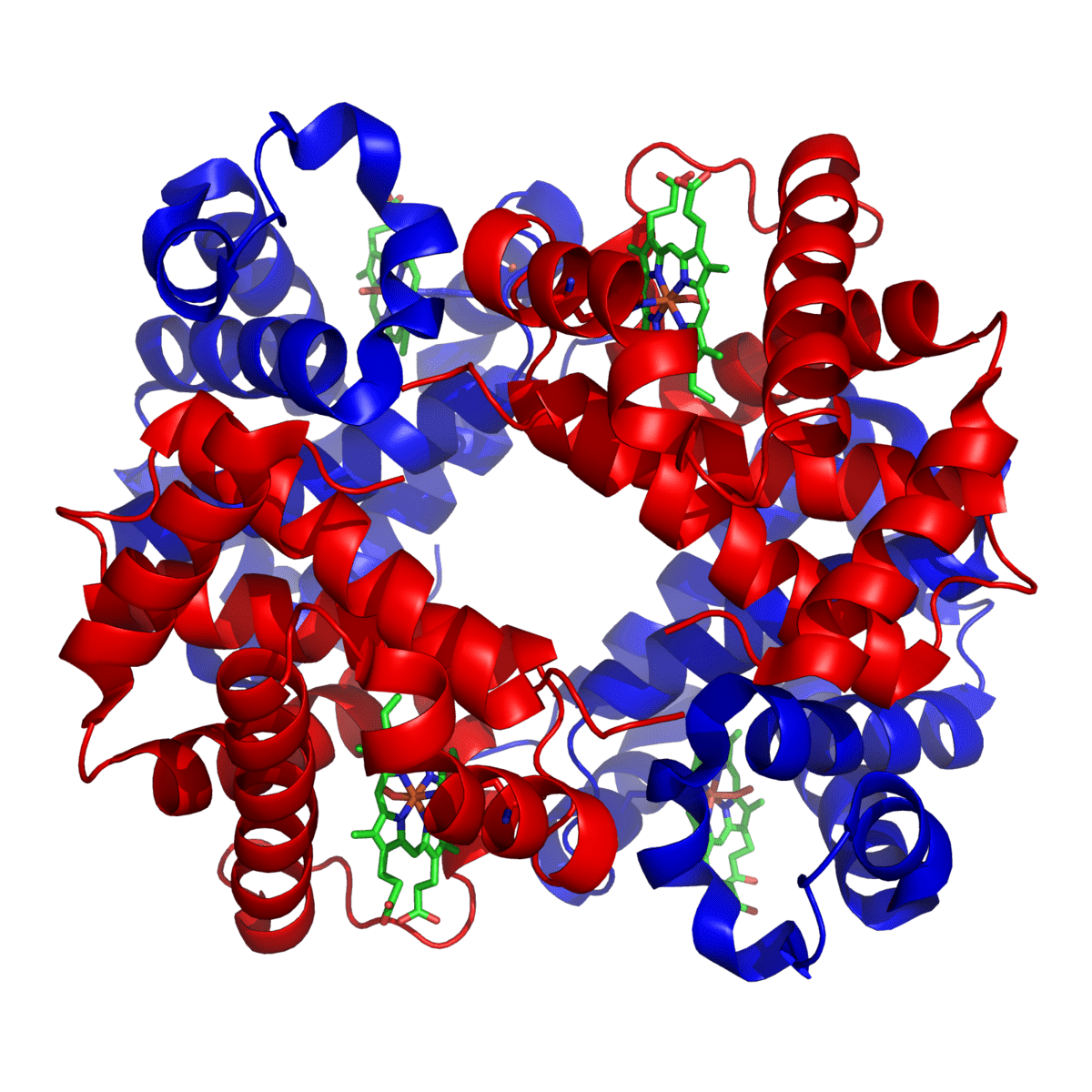

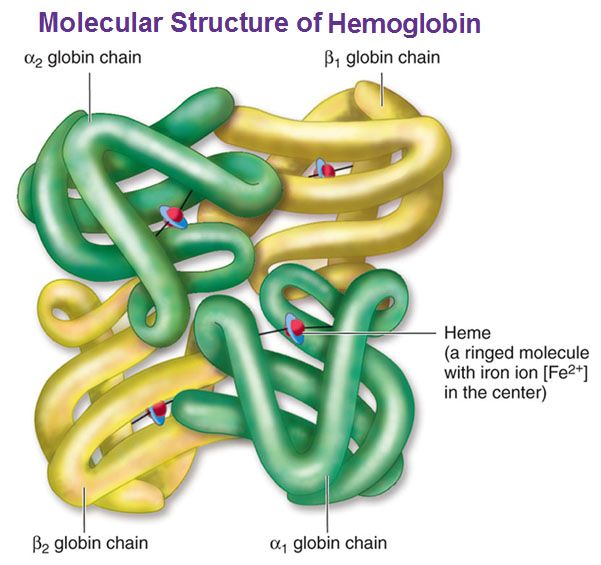

Hemoglobin is a carrier for oxygen from the lungs to the various tissues and carbon dioxide from other parts of the body to the lungs. About 70% of the body’s iron is present in the red blood cells in the form of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is an iron-protein complex that gives red blood cells its red color. It is made up of heme, which is the iron-containing portion, and globin chains, which are proteins. The globin protein consists of chains of amino acids, the “building blocks” of proteins.

There are several different types of globin chains, named alpha, beta, delta, and gamma.

Normal hemoglobin types include:

- Hemoglobin A1 (Hb A1 or Hb A): makes up about 95%-98% of hemoglobin found in adults; it contains two alpha (α) chains and two beta (β) protein chains.

- Hemoglobin A2 (Hb A2 ): makes up about 2%-3% of hemoglobin found in adults; it has two alpha (α) and two delta (δ) protein chains.

- Hemoglobin F (Hb F, fetal hemoglobin): makes up to 1%-2% of hemoglobin found in adults; it has two alpha (α) and two gamma (γ) protein chains. It is the primary hemoglobin produced by the fetus during pregnancy; its production usually falls shortly after birth and reaches adult level within 1-2 years.

Genetic changes (mutations) in the globin genes cause alterations in the globin protein, resulting in structurally altered hemoglobin, such as hemoglobin S, which causes sickle cell, or a decrease in globin chain production (thalassemia). In thalassemia, the reduced production of one of the globin chains upsets the balance of alpha to beta chains and causes abnormal hemoglobin to form (alpha thalassemia) or causes an increase of minor hemoglobin components, such as Hb A2 or Hb F (beta thalassemia).

Four genes code for the alpha globin chains, and two genes (each) code for the beta, delta, and gamma globin chains. Mutations may occur in either the alpha or beta globin genes. The most common alpha-chain-related condition is alpha thalassemia. The severity of this condition depends on the number of genes affected.

Mutations in the beta gene are mostly inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. This means that the person must have two altered gene copies, one from each parent, to have a hemoglobin variant-related disease. If one normal beta gene and one abnormal beta gene are inherited, the person is heterozygous for the abnormal hemoglobin, known as a carrier. The abnormal gene can be passed on to any children, but it generally does not cause symptoms or significant health concerns in the carrier.

If two abnormal beta genes of the same type are inherited, the person is homozygous. The person would produce the associated hemoglobin variant and may have some associated symptoms and potential for complications. The severity of the condition depends on the genetic mutation and varies from person to person. A copy of the abnormal beta gene would be passed on to any children.

If two abnormal beta genes of different types are inherited, the person is “doubly heterozygous” or “compound heterozygous”. The affected person would typically have symptoms related to one or both of the hemoglobin variants that he or she produces. One of the abnormal beta genes would be passed on to children.

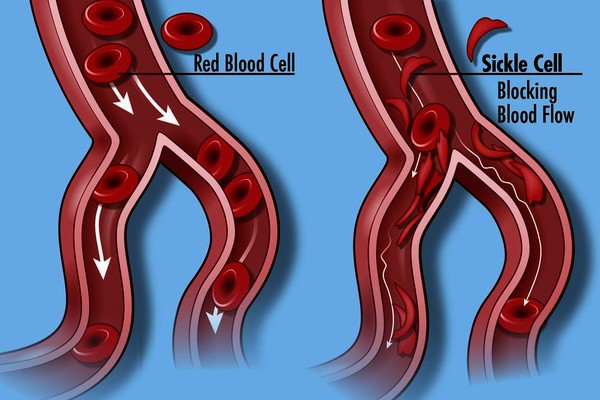

Red blood cells containing abnormal hemoglobin may not carry oxygen efficiently and may be broken down by the body sooner than usual (a shortened survival), resulting in hemolytic anemia. Several hundred hemoglobin variants have been documented, but only a few are common and clinically significant. Some of the most common hemoglobin variants include hemoglobin S, the primary hemoglobin in people with sickle cell disease that causes the red blood cell to become misshapen (sickle), decreasing the cell’s survival; hemoglobin C, which can cause a minor amount of hemolytic anemia; and hemoglobin E, which may cause no symptoms or generally mild symptoms.

A hemoglobin abnormality is a variant form of hemoglobin that is often inherited and may cause a blood disorder (hemoglobinopathy).

Hemoglobin Variants:

Several hundred abnormal forms of hemoglobin (variants) have been identified, but only a few are common and clinically significant.

Common hemoglobin variants

- Hemoglobin S: this is the primary hemoglobin in people with sickle cell disease (also known as sickle cell anemia). Approximately 1 in 375 African American babies are born with sickle cell disease, and about 100,000 Americans live with the disorder, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those with Hb S disease have two abnormal beta chains and two normal alpha chains. The presence of hemoglobin S causes the red blood cell to deform and assume a sickle shape when exposed to decreased amounts of oxygen (such as might happen when someone exercises or has an infection in the lungs). Sickled red blood cells are rigid and can block small blood vessels, causing pain, impaired circulation, and decreased oxygen delivery, as well as shortened red cell survival. A single beta (βS) copy (known as sickle cell trait, which is present in approximately 8% of African Americans) typically does not cause significant symptoms unless it is combined with another hemoglobin mutation, such as that causing Hb C or beta-thalassemia.

- Hemoglobin C: about 2-3% of African Americans in the United States are heterozygotes for hemoglobin C (have one copy, known as hemoglobin C trait) and are often asymptomatic. Hemoglobin C disease (seen in homozygotes, those with two copies) is rare (0.02% of African Americans) and relatively mild. It usually causes a minor amount of hemolytic anemia and a mild to moderate enlargement of the spleen.

- Hemoglobin E: Hemoglobin E is one of the most common beta chain hemoglobin variants in the world. It is very prevalent in Southeast Asia, especially in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, and in individuals of Southeast Asian descent. People who are homozygous for Hb E (have two copies of βE) generally have mild hemolytic anemia, microcytic red blood cells, and mild enlargement of the spleen. A single copy of the hemoglobin E gene does not cause symptoms unless it is combined with another mutation, such as the one for beta-thalassemia trait.

Less common hemoglobin variants

There are many other variants. Some are silent – causing no signs or symptoms – while others affect the functionality and/or stability of the hemoglobin molecule. Examples of other variants include Hemoglobin D, Hemoglobin G, Hemoglobin J, Hemoglobin M, and Hemoglobin Constant Spring caused by a mutation in the alpha globin gene that results in an abnormally long alpha (α) chain and an unstable hemoglobin molecule. Additional examples include:

- Hemoglobin F: Hb F is the primary hemoglobin produced by the fetus, and its role is to transport oxygen efficiently in a low oxygen environment. Production of Hb F decreases sharply after birth and reaches adult levels by 1-2 years of age. Hb F may be elevated in several congenital disorders. Levels can be normal to significantly increased in beta-thalassemia and are frequently increased in individuals with sickle cell anemia and in sickle cell-beta thalassemia. Individuals with sickle cell disease and increased Hb F often have a milder disease, as the F hemoglobin inhibits sickling of the red cells. Hb F levels are also increased in a rare condition called hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH). This is a group of inherited disorders in which Hb F levels are increased without the signs or clinical features of thalassemia. Different ethnic groups have different mutations causing HPFH. Hb F can also be increased in some acquired conditions involving impaired red blood cell production. Some leukemias and other myeloproliferative neoplasms are also associated with mild elevation in Hb F.

- Hemoglobin H: Hb H is an abnormal hemoglobin that occurs in some cases of alpha thalassemia. It is composed of four beta (β) globin chains and is produced due to a severe shortage of alpha (α) chains. Although each of the beta (β) globin chains is normal, the tetramer of 4 beta chains does not function normally. It has an increased affinity for oxygen, holding onto it instead of releasing it to the tissues and cells. Hemoglobin H is also associated with a significant breakdown of red blood cells (hemolysis) as it is unstable and tends to form solid structures within red blood cells. Serious medical problems are not common in people with hemoglobin H disease, though they often have anemia.

- Hemoglobin Barts: Hb Barts develops in fetuses with alpha thalassemia. It is formed of four gamma (γ) protein chains when there is a shortage of alpha chains, in a manner similar to the formation of Hemoglobin H. If a small amount of Hb Barts is detected, it usually disappears shortly after birth due to dwindling gamma chain production. These children have one or two alpha gene deletions and are silent carriers or have the alpha thalassemia trait. If a child has a large amount of Hb Barts, he or she usually has hemoglobin H disease and a three-gene deletion. Fetuses with four-gene deletions have hydrops fetalis and usually do not survive without blood transfusions and bone marrow transplants.

A person can also inherit two different abnormal genes, one from each parent. This is known as being compound heterozygous or doubly heterozygous. Several different clinically significant combinations are listed below.

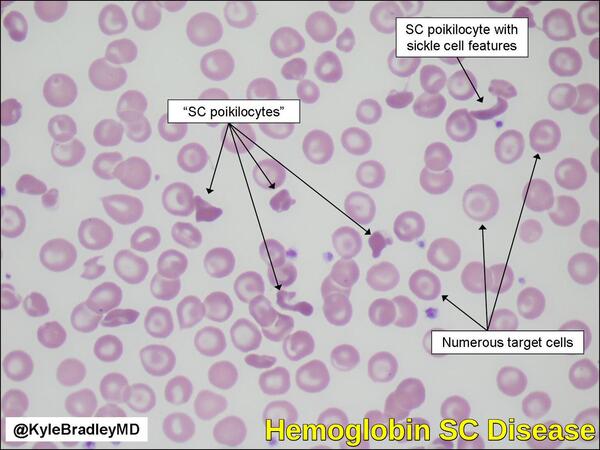

- Hemoglobin SC disease: inheritance of one beta S gene and one beta C gene results in Hemoglobin SC disease. These individuals have a mild hemolytic anemia and moderate enlargement of the spleen. Persons with Hb SC disease may develop the same vaso-occlusive (blood vessel-blocking) complications as seen in sickle cell anemia, but most cases are less severe.

- Sickle Cell – Hemoglobin D disease: individuals with sickle cell – Hb D disease have inherited one copy of hemoglobin S and one of hemoglobin D-Los Angeles (or D-Punjab) genes. These people may have occasional sickle crises and moderate hemolytic anemia.

- Hemoglobin E – beta thalassemia: individuals who are doubly heterozygous for hemoglobin E and beta thalassemia have an anemia that can vary in severity, from mild (or asymptomatic) to severe, dependent on the beta thalassemia mutation(s) present.

- Hemoglobin S – beta thalassemia: sickle cell – beta thalassemia varies in severity, depending on the beta thalassemia mutation inherited. Some mutations result in decreased beta globin production (beta+) while others completely eliminate it (beta0). Sickle cell – beta+ thalassemia tends to be less severe than sickle cell – beta0 thalassemia. People with sickle cell – beta0 thalassemia tend to have more irreversibly sickled cells, more frequent vaso-occlusive problems, and more severe anemia than those with sickle cell – beta+ thalassemia. It is often difficult to distinguish between sickle cell disease and sickle cell – beta0 thalassemia.

Signs and Symptoms:

Signs and symptoms associated with hemoglobin variants can vary in type and severity depending on the variant present and whether an individual has one variant or a combination. Some are the result of an increase in the breakdown (hemolysis) of red blood cells and a shortened RBC survival, leading to anemia. Some examples include:

- Weakness, fatigue

- Lack of energy

- Jaundice

- Pale skin (pallor)

Some serious signs and symptoms include:

- Episodes of severe pain e.g. sickle cell anemia

- Shortness of breath

- Enlarged spleen

- Growth problems in children

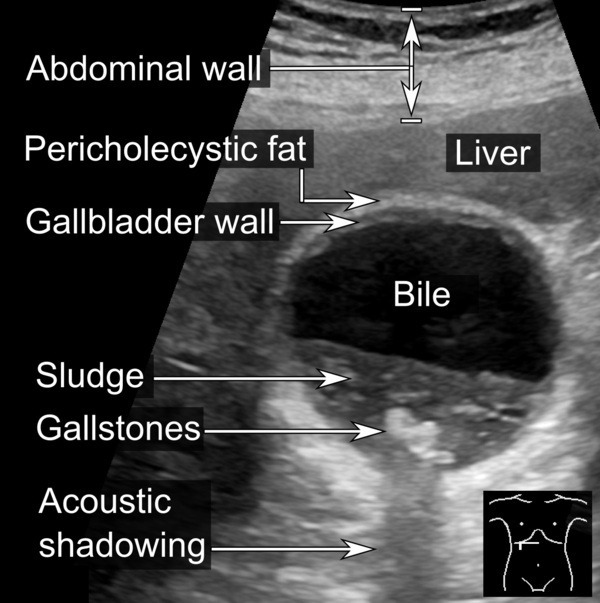

- Upper abdomen pain (due to stone formation in the gallbladder)

Investigations:

Testing for hemoglobin abnormalities (variants) is done:

- To screen for common and clinically significant hemoglobin variants in newborns. In all states, this has become a standard part of newborn screening. Infants with variants such as Hb S can benefit from early detection and treatment.

- As part of prenatal screening, on high-risk women including those with an ethnic background associated with a higher prevalence of hemoglobin variants (such as those of African descent) and those with affected family members. Screening may also be done in conjunction with genetic counseling prior to pregnancy to determine possible carrier status of potential parents.

- To identify variants in asymptomatic parents with an affected child.

- To identify hemoglobin variants in those with symptoms of unexplained anemia, with red blood cells (RBCs) that are small and/or paler than normal (microcytosis and hypochromia). It may also be ordered as part of an anemia investigation, or when someone has signs and symptoms associated with hemoglobin variants.

A stillborn fetus with alpha thalassemia major has the appearance on peripheral blood smear shown here. Note that predominantly hemoglobin Bart’s results in marked anisocytosis and poikilocytosis of RBC’s, with expansion of erythropoiesis and presence of many immature RBC’s in the peripheral blood, as evidenced by polychromasia, nucleated RBC’s and even erythroblasts seen here.

Laboratory tests

- CBC (complete blood count): The CBC is a snapshot of the cells circulating in the blood. Among other things, the CBC will tell the doctor how many red blood cells are present, how much hemoglobin is in them, and give the doctor an evaluation of the average size of the red blood cells present. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is a measurement of the size of the red blood cells. A low MCV is often the first indication of thalassemia. If the MCV is low and iron-deficiency has been ruled out, the person may be a carrier of the thalassemia trait or have a hemoglobin variant that results in smaller than normal RBCs (for example, Hb E).

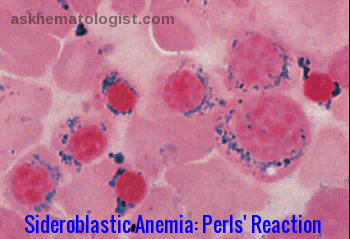

- Blood smear (also called a peripheral smear): In this test, a trained laboratorian looks under the microscope at a thin layer of blood on a slide treated with a special stain. The number and type of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets can be evaluated to see if they are normal and mature. With a hemoglobinopathy, the red blood cells may be:

- Smaller than normal (microcytic)

- Paler than normal (hypochromic)

- Varying in size (anisocytosis) and shape (poikilocytosis, e.g., sickle-shaped cells)

- Having a nucleus (nucleated red blood cell, not normal in a mature RBC) or crystal (e.g., C crystal)

- Having uneven hemoglobin distribution (producing “target cells” that look like a bull’s-eye under the microscope).

The greater the percentage of abnormal-looking red blood cells, the greater the likelihood of an underlying disorder.

- Hemoglobinopathy evaluation: These tests identify the type, and measure the relative amount of the different types of hemoglobin present in an individual’s red blood cells. Most of the common variants can be identified using one of these tests or a combination. The relative amounts of any variant hemoglobin detected can help diagnose combinations of hemoglobin variants and thalassemia (compound heterozygotes).

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis is used as a screening test to identify normal and abnormal hemoglobins and assess their quantity. Hemoglobin types include hemoglobin A1 (HbA1), hemoglobin A2 (HbA2), hemoglobin F (HbF; fetal hemoglobin), hemoglobin C (HbC), and hemoglobin S (HbS). Hemoglobin reference ranges are as follows.

Adult/elderly: Percentage of total Hb:

- HbA1: 95-98%

- HbA2: 2-3%

- HbF: 0.8-2%

- HbS: 0%

- HbC: 0%

- HbE: 0%

Children: HbF:

- Newborn: 50-80%

- < 6 months: < 8%

- >6 months: 1-2%

- Genetic testing: These tests are used to investigate deletions and mutations in the alpha and beta globin-producing genes. Family studies can be done to evaluate carrier status and the types of mutations present in other family members. Genetic testing is not routinely done but can be used to help confirm hemoglobin variants, thalassemia, and to determine carrier status.

Treatment:

Hemoglobin variants are rarely cured. The main goals in treating hemoglobin variants include relieving pain, minimizing complications and organ damage, and preventing infections. Children with sickle cell disease should have regular childhood vaccinations and influenza vaccination.

Treatment during a sickle cell crisis may involve hospitalization and supportive care, including drinking lots of fluids and taking pain medication. Sometimes blood transfusions are needed to treat severe anemia. Antibiotics are needed if sickle crisis is triggered by infection (e.g., pneumonia).

Individuals with hemoglobin variants can minimize crises by avoiding or managing situations likely to trigger episodes. These situations include overexertion, dehydration, extreme temperatures, altitude changes, smoking, and stress.

Drugs that increase hemoglobin F are available. These drugs (e.g., hydroxyurea) relieve some symptoms, but research into safer and more effective therapy continues. L-glutamine has been approved for use to reduce severe complications of sickle cell anemia. Bone marrow or stem cell transplants from a family member with normal hemoglobin are known to cure sickle cell disease. These treatments are risky and have severe side effects, so they remain rare. Gene therapy to correct the mutated gene is beginning to show promise in small trials, but it will require much more research before it is considered for widespread use.

References:

Hemoglobin Abnormalities | Lab Tests Online https://labtestsonline.org/conditions/hemoglobin-abnormalities

Sickle cell disease – GeneticsHomeReference. https://go.usa.gov/x8VbM

Dr Pooja Chhawcharia – Hemoglobin levels and its significance. https://blog.ekincare.com/2016/07/20/hemoglobin-levels-and-its-significance

Kyle Bradley, MD. Classic example of hemoglobin SC disease. https://twitter.com/KyleBradleyMD/status/758044602297413633

Lin IH, Tsai YH, Ho JL, Kuok CM (2019) Hb Bart’s Hydrops Fetalis. J Urol Ren Dis 11: 1143.

Shaffer, E. A. (2001). “Gallbladder sludge: What is its clinical significance?”. Current gastroenterology reports. 3 (2): 166–73.

Hemoglobinopathies. http://ar.utmb.edu/webpath/tutorial/hgb/hgb40.htm

Teresa Scordino, MD. ASH Image Bank: https://imagebank.hematology.org/image/60269/hemoglobin-c-crystals-and-target-cells

Pagana KD, Pagana TJ, Pagana TN. Mosby’s Diagnostic & Laboratory Test Reference. 14th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier; 2019.

Bishnu Prasad Devkota, MD. Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: Reference Range, Interpretation, Collection and Panels https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2085637-overview

Hi i need a help my mother has history of on and off Gi bleed unknown reason. Now her hb is 7g/dl, wbc is 11.1 and plasma pro bnp is 953… Please guide can this be treated without transfusion… She had multiple transfusions in past 3 years

Hello,

I would suggest to initially check her serum iron, ferritin, B12, folate, the reticulocyte count, and Hb electrophoresis.

Correct any hematinic deficiency as appropriate. The cause of the GI bleeding should be assessed by a gastroenterologist.

If she is iron deficient and she couldn’t tolerate oral iron, parenteral iron infusion could help and reduce her requirements for blood transfusion.

BW,

I received test results that indicated normal red blood cell count but with high hemoglobin (17.3)

Every time I do a search for this scenario only high rbc count articles come up.

How is it possible to have normal rbc count but with high hemoglobin? And why would this happen?

Hi Jack,

Thank you for your comment.

This simply represents secondary (reactive or relative) polycythemia which could be secondary to smoking, lung disease, anabolic steroids, or dehydration.

Keep yourself well hydrated and repeat your CBC after 8 weeks.

BW,

Ok thank you. I got more bloodwork Tuesday and this test showed 16.7 instead of 17.3.

It fluctuates that rapidly?jck

Thanks for these information

Thanks for the information .I really benefited a lot

may Allah bless you with his blessings and reward you . Ameen

Hi Mona,

Many thanks for your comment.

Pleased that you found this article helpful.

BW,

My body have sickle

cell

Hi Dinesh,

Thank you for your comment.

You can read more about sickle cell disease through this link:

Sickle Cell Disease

Best wishes,

Dr M Abdou