Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a condition characterized by peripheral blood eosinophilia with manifestations of organ system involvement or dysfunction directly related to eosinophilia in the absence of parasitic, allergic, or other secondary causes of eosinophilia. The ICD 10 code for Hypereosinophilic syndrome [HES] is D72.119.

Secondary eosinophilia is a cytokine-derived (interleukin-5 [IL-5]) reactive phenomenon. Worldwide, parasitic diseases are the most common cause, whereas, in developed countries, allergic diseases are the most common cause.

Other causes of eosinophilia include the following:

- Malignancies – Metastatic cancer, T-cell lymphoma, colon cancer

- Pulmonary eosinophilia – Loffler syndrome, Churg-Strauss syndrome, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Connective tissue disorders – Scleroderma, polyarteritis nodosa

- Skin diseases – Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Addison disease

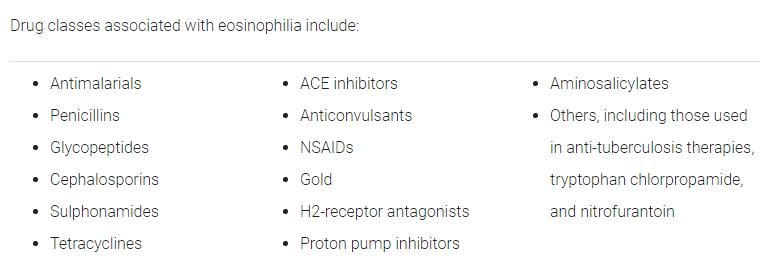

- Drug-induced eosinophilia

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia that is associated with damage to multiple organs.

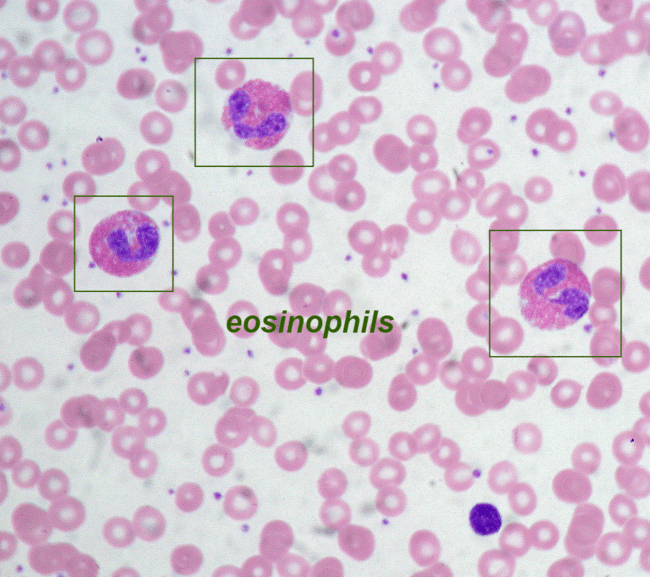

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is traditionally defined as peripheral blood eosinophilia > 1500/mcL (> 1.5 × 109/L) persisting ≥ 6 months.

In 1975, Chusid et al defined the three features required for a diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome:

- A sustained absolute eosinophil count (AEC) greater than >1500/µl, which persists for longer than 6 months

- No identifiable etiology for eosinophilia

- Signs and symptoms of organ involvement

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) was previously considered to be idiopathic but is now known to result from various disorders, some of which have known causes. One limitation of the traditional definition is that it does not include those patients with some of the same abnormalities (eg, chromosomal defects) that are known causes of HES but who do not fulfill the traditional HES definition for degree or duration of eosinophilia. Another limitation is that some patients with eosinophilia and organ damage that characterize hypereosinophilic syndrome require treatment earlier than the 6 months necessary to confirm the traditional diagnostic criteria. Eosinophilia of any etiology can cause the same types of tissue damage.

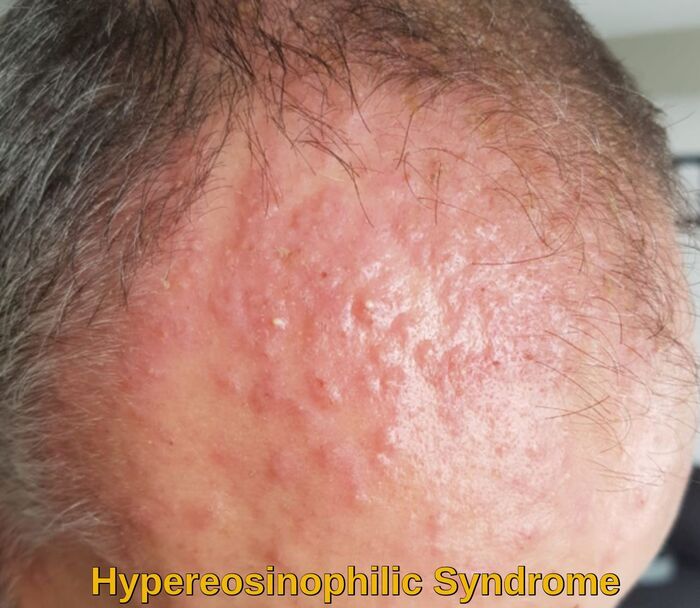

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is rare, has an unknown prevalence, and most often affects people aged 20 through 50. Only some patients with prolonged eosinophilia develop organ dysfunction that characterizes hypereosinophilic syndrome. Although any organ may be involved, the heart, lungs, spleen, skin, and nervous system are typically affected. Cardiac involvement can cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Symptoms of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES):

The signs and symptoms of HES can vary significantly depending on which part(s) of the body are affected. Frequent symptoms listed by body system include:

- Skin – rashes, itching, and edema.

- Lung – asthma, cough, difficulty breathing, recurrent upper respiratory infections, and pleural effusion.

- Gastrointestinal – abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Musculoskeletal – arthritis, muscle inflammation, muscle aches, and joint pain.

- Nervous system – vertigo, paresthesia, speech impairment, and visual disturbances.

- Heart – congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, pericardial effusion, and myocarditis.

- Blood – deep venous thrombosis, and anemia.

Affected people can also experience a variety of non-specific symptoms such as fever, weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue.

Occasionally, patients with very severe eosinophilia (eg, eosinophil counts of > 100,000/mcL [> 100 × 109/L]) develop complications of hyperleukocytosis, such as manifestations of brain or lung hypoxia (eg, encephalopathy, dyspnea, respiratory failure). Other thrombotic manifestations (eg, cardiac mural thrombi) may also occur.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome with cardiac involvement marked by a myocardial thickening (A, arrows), which resolved after corticosteroid treatment (B, arrows).

Subtypes of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES):

There are two broad subtypes of HES:

- Myeloproliferative variant

- Lymphoproliferative variant

The myeloproliferative variant is often associated with a small interstitial deletion in chromosome 4 at the CHIC2 site that causes the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene (which has tyrosine kinase activity that can transform hematopoietic cells). Patients often have:

- Splenomegaly

- Thrombocytopenia

- Anemia

- Elevated serum vitamin B12 levels

- Hypogranular or vacuolated eosinophils

- Myelofibrosis

Patients with the myeloproliferative subtype often develop endomyocardial fibrosis and may rarely develop acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Patients with the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene are more often males and may be responsive to low-dose imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor).

A small proportion of patients with the myeloproliferative variant of the hypereosinophilic syndrome have cytogenetic changes involving platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) and may also be responsive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib. Other cytogenetic abnormalities include rearrangement of the gene for fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) or janus kinase 2 (PCM1-JAK2).

The lymphoproliferative variant is associated with a clonal population of T cells with an aberrant phenotype. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) shows a clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement. Patients more often have:

- Angioedema, skin abnormalities, or both

- Hypergammaglobulinemia (especially high IgE)

- Circulating immune complexes (sometimes with serum sickness)

Patients with the lymphoproliferative variant also more often respond favorably to corticosteroids and occasionally develop T-cell lymphoma.

Other HES variants include chronic eosinophilic leukemia, Gleich syndrome (cyclical eosinophilia and angioedema), familial hypereosinophilic syndrome mapped to 5q 31-33, and other organ-specific syndromes. In organ-specific eosinophilic syndromes, eosinophilic infiltration is confined to a single organ (eg, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia).

Hyperleukocytosis may occur in patients with eosinophilic leukemia and very high eosinophil counts (eg, > 100,000 cells/mcL [> 100 × 109/L]). Eosinophils can form aggregates that occlude small blood vessels, causing tissue ischemia and microinfarctions. Common manifestations include brain or lung hypoxia (eg, encephalopathy, dyspnea, or respiratory failure).

Diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES):

Symptoms of HES are also common in many other medical problems, making an initial diagnosis more difficult. The first step is to rule out other conditions with similar symptoms. These include parasitic infection, allergic disease, cancers, autoimmune diseases, and drug reactions.

An allergist/immunologist has specialized training to effectively diagnose the problem and, if HES is present, to work collaboratively with other specialists such as a hematologist or cardiologist in the treatment and monitoring of HES.

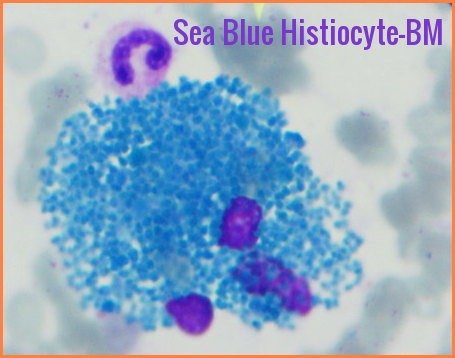

Testing is individualized according to symptoms and may include stool evaluation to detect parasitic infection, allergy testing to diagnose environmental or food allergies, biopsies of the skin or other organs, blood tests to screen for autoimmunity, CT imaging of affected organs, molecular genetic studies to detect FIP1L1-PDGFRA or other mutations to help determine, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy with flow cytometry, cytogenetic testing, and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is done to identify the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene and other possible causes of eosinophilia.

When diagnosed with HES, it is important to determine the extent of organ damage. A chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests, and echocardiogram are routinely performed to evaluate the heart and lungs. Other tests often performed in HES patients include liver and kidney function, creatine kinase, troponin, serum vitamin B12 levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and serum tryptase levels.

Treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES):

The goal of HES treatment is to reduce eosinophil levels in the blood and tissues, thereby preventing tissue damage–especially in the heart. Standard HES treatment includes glucocorticosteroid medications such as prednisone for hypereosinophilia and often for ongoing treatment of organ damage, and chemotherapeutic agents such as hydroxyurea, chlorambucil, etoposide, cladribine, and vincristine to control eosinophil counts. Interferon-alpha may also be used as a treatment. This medication must be administered by frequent injections.

Research is uncovering new therapies for HES. One new approach for controlling malignant cell growth is the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as GleevecTM (imatinib) for patients with the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene or other similar gene fusions. Monoclonal antibody therapy, such as alemtuzumab (anti-CD52) has also shown promise for the treatment of HES. In fact, based on a recent phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the monoclonal antibody Nucala or mepolizumab (anti-IL-5) has just received approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of adults and children aged 12 years and older with HES for six months or longer without another identifiable non-blood-related cause of the disease.

Treatments include immediate therapy, definitive therapies (treatments directed at the disorder itself), and supportive therapies.

Immediate therapy:

For patients with very severe eosinophilia, complications of hyperleukocytosis, or both (usually patients with eosinophilic leukemia), high-dose IV corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg or equivalent) should be initiated as soon as possible. If the eosinophil count is much lower (eg, by ≥ 50%) after 24 hours, the corticosteroid dose can be repeated daily; if not, an alternative treatment (eg, hydroxyurea) is begun. Once the eosinophil count begins to decline and is under better control, additional drugs may be started.

Definitive therapy:

Patients with the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene (or similar fusion genes) are usually treated with imatinib and, particularly if heart damage is suspected, corticosteroids. If imatinib is ineffective or poorly tolerated, another tyrosine kinase inhibitor (eg, dasatinib, nilotinib, sorafenib) can be used, or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can be used.

Patients without the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene, even if asymptomatic, are often given one dose of prednisone 60 mg (or 1 mg/kg) orally to determine corticosteroid responsiveness (ie, a decrease in the eosinophil count). In patients with symptoms or organ damage, prednisone is continued at the same dose for 2 weeks, then tapered. Patients without symptoms and organ damage are monitored for at least 6 months for these complications. If corticosteroids cannot be easily tapered, a corticosteroid-sparing drug (eg, hydroxyurea, interferon alfa) can be used.

Supportive care:

Supportive drug therapy and surgery may be required for cardiac manifestations (eg, infiltrative cardiomyopathy, valvular lesions, heart failure). Thrombotic complications may require the use of antiplatelet drugs (eg, aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine); anticoagulation is indicated if a left ventricular mural thrombus is present or if transient ischemic attacks persist despite the use of aspirin.

Investigational therapy:

Mepolizumab and other anti‐interleukin‐5 antibodies are investigational treatments for hypereosinophilic syndrome. Mepolizumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody against interleukin 5 (a regulator of eosinophil production). Mepolizumab decreases eosinophilia and the need for high-dose corticosteroid therapy and is currently available for compassionate use in the US for patients with refractory hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Prognosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES):

The prognosis of HES depends upon the extent of any organ damage. In very severe cases, HES may be fatal, but there is hope. Survival rates have improved greatly. In 1975, only 12% of HES patients survived three years. Today, more than 80% of HES patients survive five years or more.

Death usually results from an organ, particularly the heart, dysfunction. Cardiac involvement is not predicted by the degree or duration of eosinophilia. The prognosis varies depending on the response to therapy. Response to imatinib improves the prognosis among patients with the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene and other responsive gene fusions. Current therapy has improved the prognosis.

Summary:

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia, which is the presence of high levels of eosinophils in the blood. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that play a role in the immune system’s response to parasitic infections and allergies. When eosinophil levels are elevated for an extended period of time without an apparent cause, it can indicate HES.

Treatment for HES depends on the severity of the condition and the organs affected. The primary goal of treatment is to reduce eosinophil levels and prevent organ damage. This may involve medications such as corticosteroids, immunomodulators, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and chemotherapy drugs. In severe cases, stem cell transplantation may be necessary.

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome can be challenging to diagnose and treat. Medical professionals should be aware of the symptoms of HES and consider it as a potential diagnosis in patients with unexplained eosinophilia. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving outcomes in people with HES.

References:

Jane Liesveld and James P. Wilmot. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome – Hematology and Oncology – MSD Manual Professional Edition https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/eosinophilic-disorders/hypereosinophilic-syndrome?query=Hypereosinophilic%20Syndrome

Apperley JF, Gardembas M, Melo JV, et al: Response to imatinib mesylate in patients with chronic myeloproliferative diseases with rearrangements of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. N Engl J Med 347:481–487, 2002.

Gotlib J: World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 92:1243–1259, 2017.

Ogbogu PU, Bochener BS, Butterfield HJ, et al: Hypereosinophilic syndromes: A multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124:1319–1325, 2009.

Cortes J, Ault P, Koller C, et al: Efficacy of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood 101:4714–4716, 2003.

Rothenberg ME, Klion AD, Roufosse FE, et al: Treatment of patients with the hypereosinophilic syndrome with mepolizumab. N Engl J Med 358:1215–28, 2008.

What causes secondary eosinophilia? https://www.medscape.com/answers/202030-115250/what-causes-secondary-eosinophilia?

Eosinophilia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eosinophilia

Hypereosinophilic syndrome. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/2804/hypereosinophilic-syndrome

Noh HR, Magpantay GG. Hypereosinophilic syndrome. Allergy Asthma Proc. January 2017; 38(1):78-81.

Curtis C, Ogbogu P. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. April 2016; 50(2):240-251.

Fiona Larsen. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/hypereosinophilic-syndrome

Venkata Anuradha Samavedi, MBBS, MD. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. Medscape Reference. March 2017; http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/202030-overview.

Idiopathic Hypereosinophilic Syndrome with Löeffler’s Endocarditis – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Hypereosinophilic-syndrome-with-cardiac-involvement-in-our-patient-was-marked-by-a_fig2_263282480 [accessed 12 Oct, 2021]

Andrew Moore, MD – The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) – Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. https://www.aaaai.org/Conditions-Treatments/Related-Conditions/hypereosinophilic-syndrome

Drug-Induced Eosinophilia. https://diseasesandconditions.net/drug-induced-eosinophilia/

Roufosse F, Kahn J-E, Rothenberg ME, Wardlaw AJ, Klion AD, Kirby SY, Gilson MJ, Bentley JH, Bradford ES, Yancey SW, Steinfeld J, Gleich GJ. Efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in hypereosinophilic syndrome: a Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.037

Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(11):1077-89.

Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37.

Keywords:

hypereosinophilic syndrome symptoms, hypereosinophilic syndrome treatment, hypereosinophilic syndrome life expectancy, hypereosinophilic syndrome icd 10, hypereosinophilic syndrome criteria, hypereosinophilic syndrome skin, hypereosinophilic syndrome b12, hypereosinophilic syndrome rash, hypereosinophilic syndrome diagnosis, what is HES, is hypereosinophilic syndrome fatal.

I am a 37 year old female. I have been regularly donating plasma for almost two months now, but yesterday I was deferred because my hematocrit was at 35%. The nurse told me that this is still a healthy level, just too low to donate, but I am a little bewildered that this happened after I have donated at least a dozen times without incident. I was not currently on my period, and I had donated just two days prior just fine. Is there anything else besides an obvious injury that would cause a sudden drop in hematocrit? How can I reliably raise my levels before my next appointment?

Hi Erin,

Thank you for your comment.

As long as your other blood indices e.g. white cell count, hemoglobin, MCV, MCH, and platelets are fine, the low hematocrit could be caused by depleted iron stores.

I would suggest to check your serum iron, ferritin, B12, and folate.

BW,

If HES is a prothrombotic state which may get worse by corticosteroids,TKIs,So what is the pathobiology,clinical spectrum? Also;is there any role for Herdidary thrombophilia testing to guide primary or secondary thromboprohylaxis in HES?

Hi Sabry,

Thank you for your comment.

Yes, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) has been associated with a prothrombotic tendency. The increased levels of eosinophils in the blood can lead to endothelial damage and activation of clotting factors, contributing to a higher risk of thrombotic events. Additionally, eosinophils release various proinflammatory mediators that can further promote a prothrombotic state. Monitoring for thrombotic complications is important in the management of patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome, and anticoagulation may be considered in certain cases.

BW,

Dr M Abdou