Lymphatic Filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis, considered globally as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), is a parasitic disease caused by microscopic, thread-like worms. The adult worms only live in the human lymph system. The lymph system maintains the body’s fluid balance and fights infections. Lymphatic filariasis is spread from person to person by mosquitoes.

People with the disease can suffer from lymphedema and elephantiasis and in men, swelling of the scrotum, called hydrocele. Lymphatic filariasis is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide. Communities frequently shun and reject women and men disfigured by the disease. Affected people frequently are unable to work because of their disability, and this harms their families and their communities.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified lymphatic filariasis as the second leading cause of permanent and long-term disability in the world, after leprosy.

The WHO acknowledges the achievement of the Republic of Yemen for eliminating lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem, making it the second country, after Egypt, in WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region to achieve the criteria.

Lymphatic Filariasis is caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori.

Transmission is by mosquitoes. Infective larvae from the mosquito migrate to the lymphatics, where they develop into threadlike adult worms within 6 to 12 mo. Females are 80 to 100 mm long; males are about 40 mm long. Gravid adult females produce microfilariae that circulate in the blood.

Current estimates suggest that about 120 million people are infected.

Clinical features:

Infection can result in microfilaremia without overt clinical manifestations. Symptoms and signs are caused primarily by adult worms. Microfilaremia gradually disappears after people leave the endemic area.

Acute inflammatory filariasis

Consists of recurrent episodes of fever and inflammation of lymph nodes with lymphangitis or acute epididymitis and spermatic cord inflammation. Localized involvement of a limb may cause an abscess that drains externally and leaves a scar. ADL is often associated with secondary bacterial infections. ADL episodes usually precede

Localized involvement of a limb may cause an abscess that drains externally and leaves a scar. Acute adenolymphangitis is often associated with secondary bacterial infections.

Acute filariasis is more severe in previously unexposed immigrants to endemic areas than in native residents.

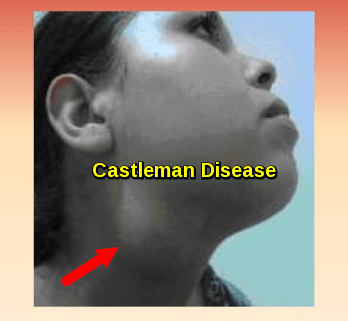

Chronic filarial disease

Develops insidiously after many years. In most patients, asymptomatic lymphatic dilation occurs, but chronic inflammatory responses to adult worms and secondary bacterial infections may result in chronic lymphedema of the affected body area. Increased local susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections further contributes to its development.

Chronic pitting lymphedema of a lower extremity can progress to elephantiasis (chronic lymphatic obstruction).

W. bancrofti can cause hydrocele and scrotal elephantiasis. Other forms of the chronic filarial disease may lead to chyluria and chyloceles.

Extralymphatic signs

Include chronic microscopic hematuria and proteinuria and mild polyarthritis, all presumed to result from immune complex deposition.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia

Uncommon manifestation with recurrent bronchospasm, transitory lung infiltrates, low-grade fever, and marked eosinophilia. It is most likely due to hypersensitivity reactions to microfilariae. It can lead to pulmonary fibrosis.

Diagnosis:

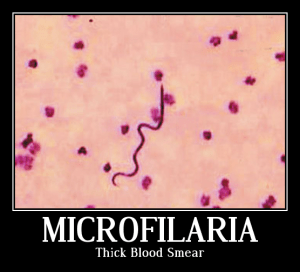

The traditional diagnostic method for filariasis is to demonstrate microfilariae in the peripheral blood or skin.

Blood samples must be obtained when microfilaremia peaks (at night where W. bancrofti is endemic, but during the day where B. malayi and B. timori occur).

Left: Microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti in thick blood smear stained with Giemsa. Right: Microfilaria of Brugia malayi in a thick blood smear, stained with Giemsa. Center: Photograph of a female Aedes aegypti mosquito as she was in the process of obtaining a “blood meal.”

Several blood tests are available:

Antigen detection: A rapid-format immunochromatographic test for W. bancrofti antigens

Molecular diagnosis: Polymerase chain reaction assays for W. bancrofti and B. malayi

Antibody detection: Alternatively, enzyme immunoassay tests for antifilarial IgG1 and IgG4

Patients with active filarial infection typically have elevated levels of antifilarial IgG4 in the blood.

Microfilariae may also be observed in chylous urine and hydrocele fluid. If lymphatic filariasis is suspected, urine should be examined macroscopically for chyluria and then concentrated to examine for microfilariae.

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) kills microfilariae and a variable proportion of adult worms. DEC 2 mg/kg po tid for 12 days is typically given; 6 mg/kg po once is an alternative.

Adverse effects with DEC are usually limited and depend on the number of microfilariae in the blood. The most common are dizziness, nausea, fever, headache, and pain in muscles or joints, which are thought to be related to release of filarial antigens.

Before treatment, patients should be assessed for coinfection with Loa loa and Onchocerca volvulus because DEC can cause serious reactions in patients with those infections.

A single dose of albendazole 400 mg po plus either ivermectin (200 mcg/kg po) in areas where onchocerciasis is co-endemic or DEC (6 mg/kg) in areas without onchocerciasis and loiasis rapidly reduces microfilaremia levels, but ivermectin does not kill adult worms. A number of drug combinations and regimens have been used in mass treatment programs.

Also, doxycycline has been given long-term (eg, 100 mg po bid for 4 to 8 wk). Doxycycline kills certain bacteria within filaria, leading to the death of the worms.

Chronic lymphedema requires meticulous skincare, including the use of systemic antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections; these antibiotics may slow or prevent progression to elephantiasis. Whether DEC therapy prevents or lessens chronic lymphedema remains controversial. Conservative measures such as elastic bandaging of the affected limb reduce swelling. Surgical decompression using nodal-venous shunts to improve lymphatic drainage offers some long-term benefit in extreme cases of elephantiasis. Massive hydroceles can also be managed surgically.

Prevention:

Fifteen countries are now acknowledged for achieving elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem.

Avoiding mosquito bites in endemic areas is the best protection.

Chemoprophylaxis with DEC or combinations of antifilarial drugs can suppress microfilaremia and thereby reduce transmission of the parasite by mosquitoes in endemic communities.

DEC has even been used as an additive to table salt in some endemic areas.

References:

CDC – Lymphatic Filariasis https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/index.html

Despite challenges, Yemen eliminates lymphatic filariasis https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/news/yemen-eliminates-lymphatic-filariasis/en/