Castleman Disease

What is Castleman Disease?

Castleman disease (CD) is a rare disease of lymph nodes and related tissues. It was first described by Dr. Benjamin Castleman in the 1950s. It is also known as Castleman’s disease, giant lymph node hyperplasia, and angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (AFH).

Castleman disease is not cancer. Instead, it is called a nonclonal lymphoproliferative disorder. This means there is an abnormal overgrowth of cells of the lymphatic system that is similar in many ways to lymphomas (cancers of lymph nodes).

Even though CD is not officially cancer, one form of this disease (known as Multicentric Castleman Disease) acts very much like lymphoma. In fact, many people with this disease eventually develop lymphomas. And like lymphoma, CD is often treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy. This is why it is included in the American Cancer Society’s cancer information.

Castleman disease is first classified based on the number of regions of enlarged lymph nodes that demonstrate these abnormal features. Unicentric Castleman Disease (UCD) involves a single enlarged lymph node or a single region of enlarged lymph nodes whereas Multicentric Castleman Disease (MCD) involves multiple regions of enlarged lymph nodes.

There are two sub-types of MCD. A subset of MCD is caused by human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8; also known as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus). These cases are called HHV-8-associated MCD. There are also MCD patients who are negative for the HHV-8 virus, and the cause is unknown. These cases are called HHV-8 negative or “idiopathic” MCD (iMCD). Castleman disease can also be described as hyaline-vascular, plasmacytic, mixed, and plasmablastic. based on the microscopic appearance. The usefulness of this sub-typing is unclear.

Castleman Disease Causes:

It’s not clear what causes Castleman disease. However, infection by a virus called human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is associated with multicentric Castleman disease.

The HHV-8 virus has also been linked to the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancerous tumor that can be a complication of HIV/AIDS. Studies have found that HHV-8 is present in nearly all HIV-positive people who have Castleman disease, and in about half of HIV-negative people with Castleman disease.

If a patient has multiple regions of enlarged lymph nodes with CD features identified by a pathologist under the microscope AND is HIV-negative and his/her lymph node and blood sample are HHV-8-negative, he/she may have HHV-8-negative or idiopathic MCD (iMCD).

Castleman disease can affect people of any age. But the average age of people diagnosed with unicentric Castleman disease is 35. Most people with the multicentric form are in their 50s and 60s. The multicentric form is also slightly more common in men than in women.

The risk of developing multicentric Castleman disease is higher in people who are infected with HHV-8 virus.

Castleman Disease Signs & Symptoms:

Interleukin 6 (IL6) plays an important role in the pathophysiology of the disease, symptomatology, and as a potential therapeutic target. CD occurs at a relatively younger age with the highest incidence in mid-thirties to forties.

Many people with unicentric Castleman disease don’t notice any signs or symptoms. The enlarged lymph node may be detected during a physical exam or an imaging test for some unrelated problem.

Some people with unicentric Castleman disease might experience signs and symptoms more common to multicentric Castleman disease, which may include:

- Fever

- Unintended weight loss

- Fatigue

- Night Sweats

- Nausea

- Enlarged liver or spleen

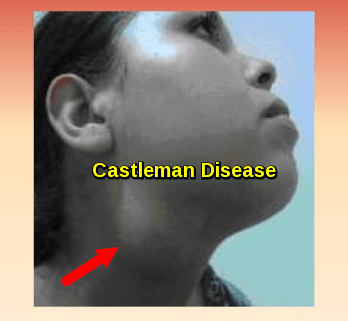

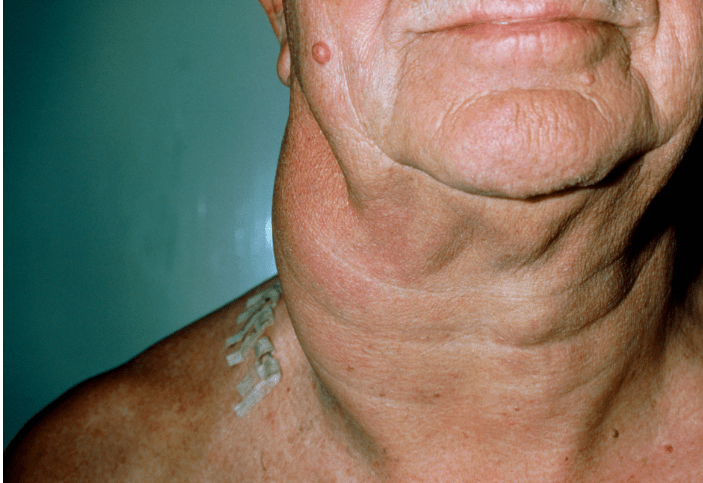

The enlarged lymph nodes associated with multicentric Castleman disease are most commonly located in the neck, collarbone, underarm and groin areas.

IMCD involves multicentric lymphadenopathy with characteristic “CD-like” lymph node histopathology and a number of signs and symptoms as defined by the 2017 International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria of iMCD, which may progress or remit/relapse over time:

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Renal dysfunction and/or proteinuria

- Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia

- Flulike symptoms (night sweats, fever, weight loss, fatigue) which are related to high serum IL6 level.

- Large liver and/or spleen

- Fluid accumulation (edema, anasarca, ascites, pleural effusion)

- Eruptive cherry hemangiomatosis or violaceous papules

- Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis

Diagnosis:

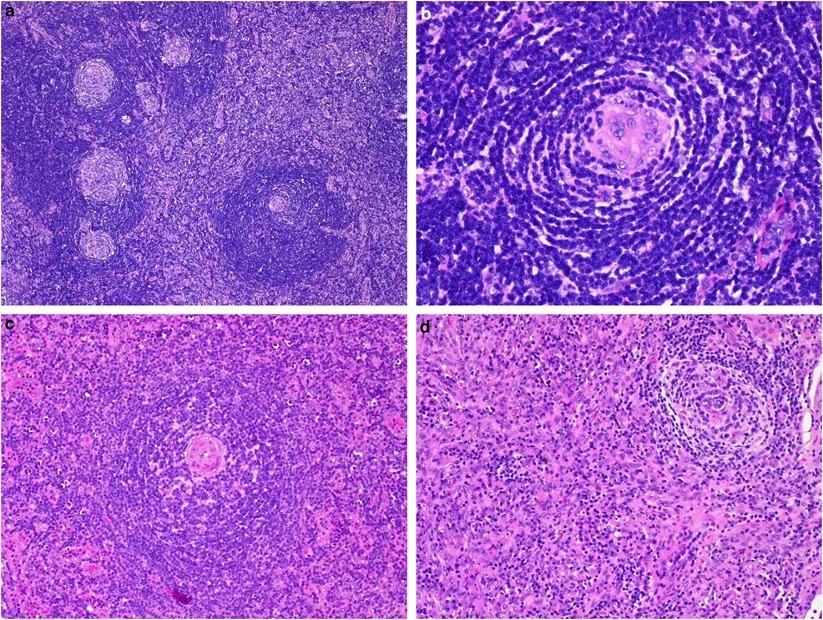

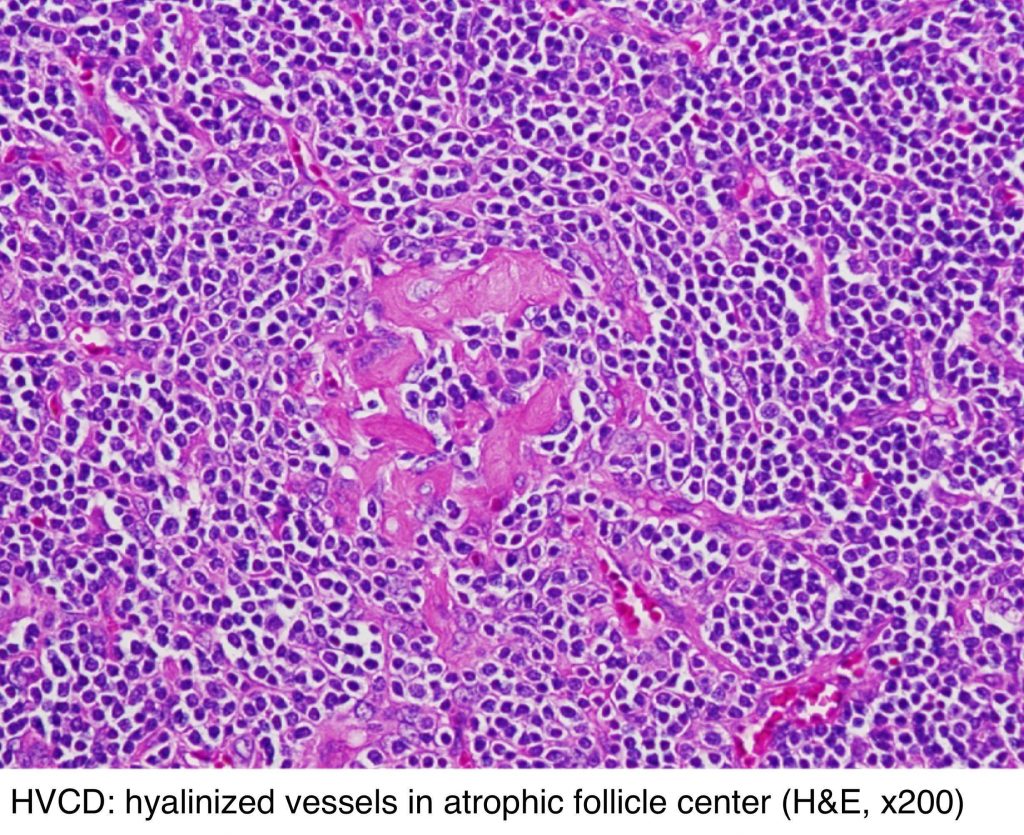

Pathologic evaluation of lymph node biopsy is essential for diagnosis. There are two basic types: hyaline-vascular type, and plasmacytic variant, with occasional cases having a mixed picture. In the hyaline-vascular type of the CD, lymph node biopsy shows angiofollicular hyperplasia with depleted germinal center cells and concentric expansion of mantle zones with small lymphocytes (onion skin appearance). The pathology shows hyalinized blood vessels as well as the presence of follicular dendritic cells, but lack of plasma cells. The increased blood vessels are considered to be related to the production of VEGF, which is produced in the presence of and by elevated IL6. Follicular cells seen in hyaline vascular CD express CD20 and CD5 but are not clonal.

Pathologic features of Castleman disease. The classical type of hyaline-vascular Castleman disease shows lymphoid hyperplasia with a broad mantle zone and interfollicular vascular hyperplasia.

The plasmacytic variant of CD shows an interfollicular increase in polyclonal plasma cells. The lymphoid architecture is relatively preserved but there are hyperplastic follicles. The mixed type of CD shows features representing both hyaline-vascular type and plasmacytic type.

Castleman disease, plasma cell variant. Lymph node biopsy with reactive follicle, hyperplastic germinal center, interfollicular plasma cell infiltrate and lack of vascular proliferation. Original magnification ×200.

Ninety percent of the unicentric CD is hyaline vascular; while 80 to 90% of the multicentric CD is either plasmacytic or mixed type.

A very small number of patients, usually multicentric plasmacytic variant, may evolve into lymphoma.

The diagnosis of Castleman’s disease should be expected in patients with a localized lymph node enlargement or a generalized lymphadenopathy with typical IL6 related symptoms including fever, night sweats, fatigue, and weight loss.

Additional symptoms as described above may include those due to localized mass or due to the production of cytokines (VEGF). The physical examination will mainly demonstrate the presence of either localized or generalized lymphadenopathy. Also, patients may present with dermatological or neurological manifestations of the disease, or with signs and symptoms associated with autoimmune disorders and/or anemia, if present.

In general, the signs and symptoms associated with CD are non-specific and are not sufficient to establish the diagnosis. There is no single pathognomonic presenting feature, and biopsy of the lymph node and histological confirmation remains the only absolute test for diagnosis. In a number of situations, the investigations are performed to exclude other conditions, especially malignant diseases.

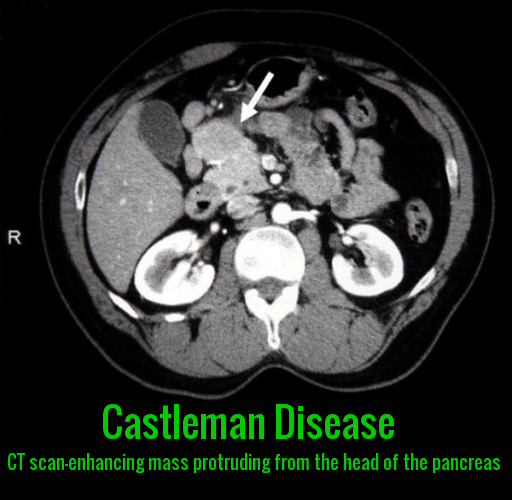

Computed tomography (CT) scan of neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis is essential for both diagnosing CD and to stage it between unicentric versus multicentric disease. The CT scan will also help identify the presence of hepatosplenomegaly.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET – CT) is also helpful as lymph nodes from CD are positive with low SUV (Standard Uptake Value). It helps differentiate between lymphoma and other malignancies, where the lymph nodes have a much higher SUV.

Differential Diagnosis:

The differential diagnosis of CD is broad and includes disorders that are overlapping with lymphadenopathy, as well as pathological findings.

All the possible causes of localized or generalized lymphadenopathy should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis of CD. The first and the foremost conditions to be excluded are the malignant disorders, specifically non-Hodgkin’s or Hodgkin’s lymphoma, as these diseases require a different and specific therapeutic intervention. None of the laboratory studies are able to differentiate malignant conditions from CD, and lymph node biopsy with appropriate histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis is essential for diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and connective tissue diseases. Their diagnosis would also depend on both clinical differentiation, as well as various serological testing.

The pathological evaluation and differential diagnosis include most importantly identification and differentiation of reactive lymphadenopathy observed in a number of diseases. This again includes autoimmune diseases such as connective tissue disorders and collagen vascular diseases, HIV and other immunodeficiency related lymphadenopathy, as well as infection etiologies.

Treatment:

For localized (unicentric) disease, surgical removal of the affected lymph node(s) usually results in a cure. However, recurrences of UCD have been reported. In some cases, ionizing radiation (radiotherapy) has proven effective.

For iMCD, chemotherapy had been the cornerstone of treatment but has been largely supplanted by newer, more directed therapies. These include drugs which target and neutralize IL-6 (siltuximab or Sylvant) or the receptor for IL-6 (tocilizumab or Actemra). In 2014, Sylvant (siltuximab) was approved to treat patients with iMCD. This is the first and only FDA-approved drug to treat patients with iMCD. Approximately half of the iMCD patients do not improve with IL-6 neutralization. These patients are often treated with chemotherapy or newer treatment options such as rituximab, sirolimus, or anakinra.

Additional symptomatic and supportive therapy may include corticosteroids or autologous bone marrow transplantation (used most frequently for severe disease or iMCD associated with POEMS syndrome).

For HHV-8-associated MCD, rituximab to eliminate the B lymphocyte is often used. It is highly effective for HHV-8-associated MCD, but occasionally antivirals and/or cytotoxic chemotherapies are needed.

Tocilizumab (Actemra), manufactured by Roche Pharmaceuticals in the United States, showed substantial efficacy in the treatment of iMCD in a small study from Japan. The drug was approved by the FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and can be prescribed “off-label” for the treatment of Castleman. Treatment requires monthly intravenous injections.

Prognosis:

The prognosis of CD varies depending on the type and severity of the disease. UCD has an excellent prognosis with surgical excision alone. MCD has a more variable prognosis and can be fatal if left untreated or if there is organ dysfunction.

Summary:

Castleman disease is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder that can affect individuals of any age, gender, or ethnicity. It can be classified into two major types: unicentric CD and multicentric CD. The diagnosis of CD is based on a combination of clinical presentation, imaging studies, and biopsy of the affected tissue. The treatment of CD depends on the type and severity of the disease, and targeted therapies have shown promise in treating MCD. CD has a variable prognosis depending on the subtype and severity of the disease.

References:

Nikhil Munshi. Castleman’s disease https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/hematology/castlemans-disease-2/

Castleman Disease – NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders) https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/castlemans-disease/

What Is Castleman Disease? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/castleman-disease/about/what-is-castleman-disease.html

David Fajgenbaum, MD, MBA, MSc. Castleman disease. National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/castlemans-disease/

Castleman disease – Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/castleman-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20370735

About Castleman Disease. Castleman Disease Collaborative Network. https://www.cdcn.org/about-castleman-disease

Neetu Radhakrishnan, MD. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2219018-overview Castleman Disease: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology

Kung-Chao Chang et al. Monoclonality and cytogenetic abnormalities in hyaline vascular Castleman disease – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Pathologic-features-of-Castleman-disease-The-classical-type-of-hyaline-vascular_fig2_258347640 [accessed 26 Jun, 2019]

Jaya Balakrishna, M.D. Lymph nodes – not lymphoma. Inflammatory disorders (noninfectious)- Castleman disease. http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphnodescastleman.html

Ibrahiem Saeed and Ali M Al-Amri. Castleman disease. The Korean journal of hematology 47(3):163-77 · September 2012

Castleman Disease (CD). https://www.dovemed.com/diseases-conditions/castleman-disease-cd/

Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, et al. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2017;129(12):1646-1657.

van Rhee F, Stone K, Szmania S, Barlogie B, Singh Z. Castleman disease in the 21st century: an update on diagnosis, assessment, and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018;16(7):482-498.

El-Osta HE, Kurzrock R. Castleman’s disease: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics. Oncologist. 2011;16(4):497-511.

report says exactly mentioned below while investigating an incidental finding of gamma globulinemia.High resolution protein electrophoresis shows densely staining monoclonal gammopathy (M spike) in gamma globulin region.Immunofixation shows IgA and lambda.Polyclonal gamma globulin to mainly consists of IgG,kappa,lambda and fair amount of IgA.

Now patient details is Age 78, Hypertriglyceridaemia with Diffuse fatty liver and border line diabetic controlled by diet and discipline.Patients recent complain vertigo only.He had high ESR above 100 and slight anaemia Hb 10.9 with creatinine 1.4.So i went for skeletal survey with normal findings but protein electrophoresis found abnormal gammopathy.So sent for immunofixation that gave the above mentioned report.

So can i get some guidance regarding this patients management?My D/D is MGUS or MGRS.

Hello,

Thank you for your message.

How much the paraprotein quantitation and serum calcium level?

I would recommend bone marrow examination to out rule myeloma.

Best wishes,