Pure Red Cell Aplasia

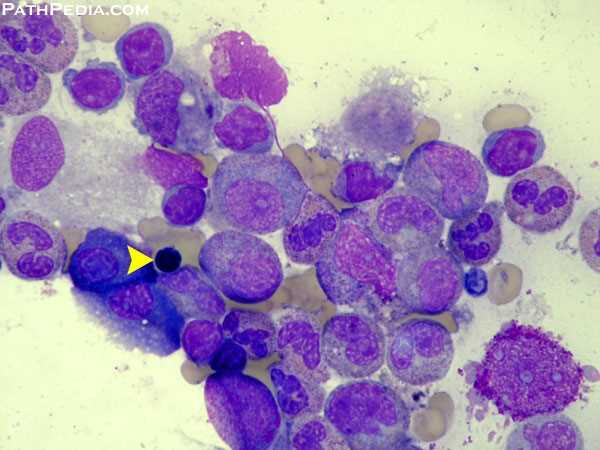

Bone marrow aspirate in Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA) demonstrating severe erythroid hypoplasia; the yellow arrow marks a single late erythroblast in an otherwise markedly depleted erythroid series.

Introduction:

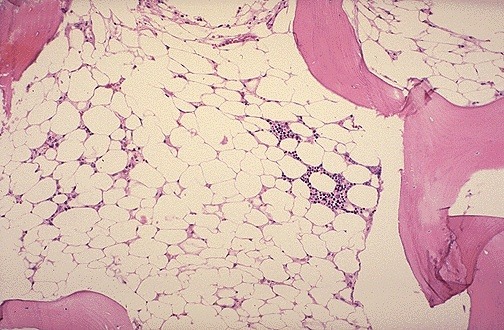

Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA) is a rare hematologic disorder characterized by a selective failure of erythropoiesis, resulting in profound anemia with markedly reduced or absent reticulocytes. Although erythroblasts are virtually absent in the bone marrow, granulopoiesis and thrombopoiesis remain intact, allowing white blood cell and platelet counts to stay within normal limits. The anemia is typically normocytic but may occasionally present as macrocytic.

Diagnostic hallmarks include severe anemia, a reticulocyte count below 1%, and fewer than 0.5% mature erythroblasts in an otherwise normocellular marrow. PRCA may be acute or chronic, acquired or congenital, and can appear as a transient, reversible condition in specific clinical contexts.

Transient erythroblastopenia of childhood (TEC) commonly follows viral infections, while PRCA associated with medications, infections, or immune-mediated mechanisms often resolves once the underlying trigger is addressed.

Understanding the causes, clinical features, and diagnostic approach is essential for guiding targeted therapy and improving patient outcomes.

Classification of PRCA:

PRCA can be broadly categorised into acute and chronic forms, with chronic PRCA further subdivided into congenital and acquired types. Understanding these categories is essential for guiding diagnosis, identifying underlying causes, and tailoring management.

Acute PRCA:

Parvovirus B19–related Pure Red Cell Aplasia

Acute PRCA most commonly results from parvovirus B19 infection, particularly in patients with underlying congenital hemolytic anemias such as hereditary spherocytosis or sickle cell disease. The virus directly targets erythroid progenitors, leading to abrupt erythroid maturation arrest and a transient aplastic crisis.

- Typically self-limiting, resolving as viral replication ceases.

- Known cause of Fifth disease in the general population.

- Characterised by sudden severe anemia and near-absent reticulocytes.

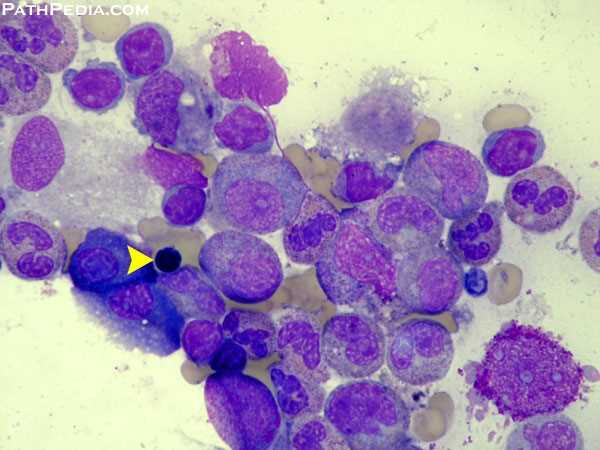

Bone marrow smear showing a giant proerythroblast with a central intranuclear viral inclusion, a classic feature of parvovirus B19–induced Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA).

Chronic PRCA:

Chronic PRCA may be congenital or acquired, with clinical severity and long-term treatment needs varying substantially.

A. Congenital PRCA – Diamond–Blackfan Anemia (DBA)

Diamond–Blackfan anemia is a rare congenital form of PRCA caused by defects in ribosomal protein genes.

- Usually inherited, though the precise inheritance pattern varies.

- Often associated with congenital anomalies, particularly craniofacial, cardiac, or upper limb abnormalities.

- Anemia typically presents in early infancy, although later onset is possible.

- Bone marrow shows marked erythroid hypoplasia with very few normoblasts.

- Hemoglobin F (HbF) is frequently elevated.

- Many patients respond to corticosteroids, while others require long-term red cell transfusion support, and selected cases may benefit from stem cell transplantation.

B. Acquired Chronic PRCA

Acquired PRCA is far more common in adults and may be idiopathic or secondary to an identifiable condition.

Idiopathic PRCA:

Represents the majority of adult cases with no identifiable underlying cause; immune-mediated suppression of erythropoiesis is frequently implicated.

Secondary PRCA:

Occurs in association with a range of clinical conditions, including:

- Thymoma (often detected via CT scanning of the anterior mediastinum)

- Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis

- Lymphoproliferative disorders and other hematologic malignancies

- Solid tumors

- Drugs, infections (other than parvovirus), and post-transplant immune dysregulation

CT chest demonstrating a well-defined anterior mediastinal mass consistent with thymoma, a recognised cause of secondary Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA).

Recognition of secondary causes is crucial, as targeted treatment of the underlying disorder often leads to remission.

Treatment:

Management of PRCA depends on the underlying etiology and the severity of anemia. Treatment aims to correct the red cell aplasia, address reversible triggers, and manage complications associated with chronic transfusion therapy.

1. Supportive Care

Patients with severe symptomatic anemia should receive red blood cell transfusions as initial stabilising therapy. Anemia tends to be more profound in PRCA cases with concurrent hemolysis, such as parvovirus-induced aplastic crises in congenital hemolytic anemias.

2. Removal of Reversible Causes

Medications implicated in PRCA should be immediately discontinued.

In children, treatment is generally conservative: PRCA is often transient and self-limited, and corticosteroids should be avoided when possible to prevent growth retardation. Transfusion support is provided if clinically indicated.

3. Treatment of Infections

Underlying infections should be managed appropriately.

For parvovirus B19–related PRCA, high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is the treatment of choice and often results in rapid correction of the aplasia.

PRCA due to infections or medications typically resolves within weeks to months once the trigger is eliminated.

4. Management of Secondary PRCA

Treatment should target the underlying disease, including:

- Thymoma – Consider surgical resection or gamma irradiation of the thymus. Improvement in PRCA may occur following tumour removal.

- Autoimmune diseases such as SLE or rheumatoid arthritis

- Hematologic malignancies, including T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia

- Solid tumors

Addressing these conditions often leads to improvement or resolution of PRCA.

5. Immunosuppressive Therapy

For idiopathic or autoimmune PRCA, first-line treatment typically involves corticosteroids, with expected responses in approximately 45% of patients within 4–6 weeks. Corticosteroids must be used cautiously in children due to growth concerns.

Additional immunosuppressive agents have demonstrated efficacy, including:

- Cyclosporine A (high response rate and commonly used)

- Cyclophosphamide

- Azathioprine

- 6-Mercaptopurine

- Rituximab (particularly in B-cell–mediated PRCA)

- Antithymocyte globulin (ATG)

- Danazol (effective in some adults but contraindicated in children)

- Plasmapheresis to remove pathogenic autoantibodies in select refractory cases

Immunotherapy may also be required for erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA)–induced PRCA to reverse anti-EPO antibody–mediated marrow suppression.

6. Stem Cell Transplantation

Both autologous and non-myeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation have been used in refractory PRCA, particularly in younger patients with persistent transfusion dependence.

7. Management of Iron Overload

Patients receiving chronic transfusions should be monitored for iron loading.

Iron chelation therapy, such as deferasirox (Exjade), is recommended when iron overload is confirmed to prevent cardiac, hepatic, and endocrine complications.

Prognosis:

The prognosis of Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA) varies widely and is determined largely by the underlying cause and response to therapy. Patients with transient PRCA, particularly parvovirus B19–related cases or drug-induced erythroid suppression, generally experience complete recovery within weeks to months once the trigger is addressed. In contrast, individuals with chronic acquired or idiopathic autoimmune PRCA often require long-term immunosuppressive therapy, though many achieve partial or complete remission with corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or other agents. PRCA associated with thymoma, autoimmune diseases, or hematologic malignancies has a more variable course and improves when the primary condition is effectively treated. Long-standing PRCA may lead to transfusion dependence and secondary iron overload, necessitating iron chelation. With appropriate evaluation and tailored management, most patients can achieve sustained hematologic stability, although relapse may occur and ongoing monitoring is essential.

Summary:

Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA) is a rare hematologic syndrome characterised by normocytic, normochromic anemia, severe reticulocytopenia, and a marked reduction or complete absence of erythroid precursors in an otherwise normal bone marrow. PRCA may be congenital, as in Diamond–Blackfan anemia, or acquired, which can occur as a primary autoimmune disorder or secondary to a wide range of systemic conditions. Primary acquired PRCA is most often antibody-mediated, whereas secondary PRCA may arise in association with autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), lymphoproliferative disorders (such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia or T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia), myelodysplastic syndromes, solid tumors, thymoma, drug toxicity, or infections, particularly parvovirus B19.

Management is guided by the underlying etiology. While some cases resolve with removal of the precipitating factor or treatment of infection, many patients require targeted immunosuppressive therapy. Among available options, cyclosporine A, alone or in combination with corticosteroids, has demonstrated the highest response rates and remains the cornerstone of therapy in idiopathic and immune-mediated forms of PRCA. Recognition of the specific pathogenic subtype is essential for selecting the most effective treatment and achieving sustained hematologic remission.

Questions and Answers:

What is Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA)?

PRCA is a rare bone marrow disorder characterized by severe reticulocytopenia, normocytic anemia, and a marked reduction or absence of erythroid precursors while white cell and platelet production remain normal.

What causes Pure Red Cell Aplasia?

PRCA can be congenital, autoimmune, infection-related, medication-induced, or secondary to conditions such as thymoma, lymphoproliferative disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, or myelodysplastic syndromes.

How does parvovirus B19 lead to PRCA?

Parvovirus B19 infects erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, producing giant proerythroblasts with viral inclusions and causing a sudden maturation arrest that results in severe anemia and very low reticulocyte counts.

What does a giant proerythroblast with viral inclusions indicate?

A giant proerythroblast containing central intranuclear inclusions is considered pathognomonic for parvovirus B19-associated Pure Red Cell Aplasia.

What is the relationship between thymoma and PRCA?

Thymoma is a well-recognized cause of secondary PRCA. Removal or treatment of the thymoma may lead to improvement or remission of PRCA in some patients.

How is PRCA diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on bone marrow examination showing markedly reduced erythroid precursors, severe reticulocytopenia, normal myeloid and megakaryocytic lines, and appropriate testing for secondary causes such as parvovirus B19, thymoma, autoimmune disease, or malignancy.

What is the difference between congenital and acquired PRCA?

Congenital PRCA, such as Diamond–Blackfan anemia, presents early in life and may be associated with congenital anomalies, whereas acquired PRCA occurs later and is often autoimmune or secondary to infections, malignancies, or drugs.

Is Pure Red Cell Aplasia reversible?

Many forms of PRCA are reversible, especially when triggered by medications, infections, or transient parvovirus B19 suppression. Others, particularly autoimmune or idiopathic cases, may require long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

What treatments are used for PRCA?

Treatment depends on the cause and may include transfusions, removal of offending drugs, IVIG for parvovirus infection, surgical management of thymoma, and immunosuppression such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine A, rituximab, or ATG.

How effective is cyclosporine A in PRCA?

Cyclosporine A, alone or combined with corticosteroids, is considered the most effective immunosuppressive therapy for idiopathic or autoimmune PRCA, with high response rates and durable remissions.

What is the prognosis for patients with PRCA?

Prognosis varies by etiology. Parvovirus-related and drug-induced PRCA typically resolve completely, while autoimmune or thymoma-associated PRCA may require long-term therapy but often respond well to targeted treatment.

When should iron chelation be used in PRCA?

Patients who become transfusion-dependent may develop iron overload; iron chelation with agents like deferasirox (Exjade) is recommended once iron excess is documented.

References:

Means, R.T. Jr. Pure red cell aplasia. Blood. Available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/128/21/2504

Means, R.T. Jr. Pure red cell aplasia. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2016;2016(1):51–56. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.51. PMID: 27913462; PMCID: PMC6142432

Schick, P.; Besa, E.C. Pure Red Cell Aplasia: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology. Medscape. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/205695-overview

Hoffman, R.; Benz, E.J.; Silberstein, L.E.; Heslop, H.; Weitz, J.; Anastasi, J. Biology of Erythropoiesis, Erythroid Differentiation, and Maturation. In: Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2013.

Young, N.S. Pure Red Cell Aplasia. In: Williams Hematology. 9th ed. Kaushansky K, Lichtman M.A., Prchal J.T., Levi M.M., Press O.W., Burns L.J., Caligiuri M.A., editors. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:539–548.

Herbert, K.E.; Prince, H.M.; Westerman, D.A. Pure red-cell aplasia due to parvovirus B19 infection in a patient treated with alemtuzumab. Blood. 2003;101:1654.

Keywords:

pure red cell aplasia, PRCA, parvovirus B19 PRCA, giant proerythroblast inclusion, thymoma PRCA, autoimmune pure red cell aplasia, acquired PRCA, congenital PRCA, Diamond Blackfan anemia, idiopathic PRCA, secondary PRCA, erythroid aplasia, reticulocytopenia, erythroblast depletion, bone marrow erythroid hypoplasia, parvovirus B19 infection anemia, pure red cell aplasia treatment, cyclosporine PRCA therapy, IVIG parvovirus anemia, thymoma-associated PRCA, PRCA diagnosis, bone marrow smear PRCA, PRCA prognosis, refractory pure red cell aplasia, immunosuppressive therapy PRCA, erythropoietin antibody PRCA, PRCA differential diagnosis, aplastic crisis parvovirus, erythropoiesis suppression, hematologic disorders PRCA

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

May i have any contact information for appointment with the doctor. I have a 3-4 year old nephew who is right now suffering with the Pure Red Cell Aplasia.

Hi Jawad,

Thank you for your comment.

I would suggest sending me his CBC and any other previous investigations including bone marrow in a private message through our “contact us” form or our email in**@*************st.com to have a look and advise.

Regards,