Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria

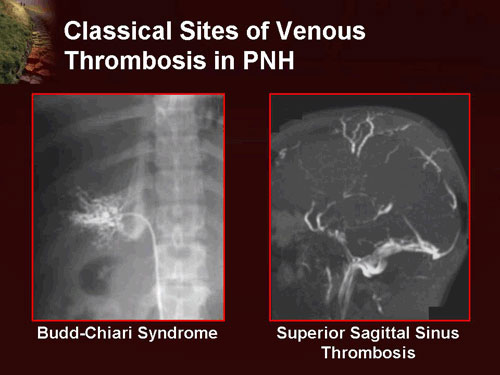

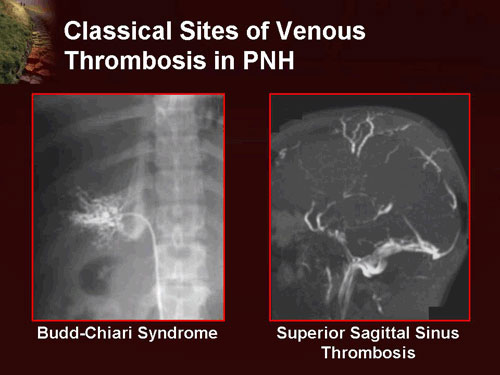

Classical venous thrombosis sites in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), including Budd–Chiari syndrome and superior sagittal sinus thrombosis.

Introduction:

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare, acquired, life-threatening hematologic disorder characterized by complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis, a marked tendency for thrombosis, and varying degrees of bone marrow failure. It is the only form of hemolytic anemia caused by an acquired intrinsic defect of the red blood cell membrane rather than an inherited abnormality. This defect results from a mutation in the PIG-A gene, leading to deficiency of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protective proteins on blood cells. As a consequence, red blood cells become abnormally sensitive to complement-induced destruction.

PNH affects approximately 1–1.5 individuals per million worldwide and predominantly presents in young adulthood, with a median age at diagnosis between 35 and 40 years, although pediatric cases do occur. The disease has a well-established association with aplastic anemia, with up to 30% of newly diagnosed PNH cases evolving from aplastic anemia, and a similar proportion of patients developing PNH following immunosuppressive therapy for aplastic anemia. The defective stem cell clone in PNH gives rise to all affected blood cell lines, including red cells, white cells, and platelets, leading to the clinical triad of hemolysis, thrombosis, and infection risk. Although the PIG-A gene is located on the X chromosome and both sexes may be affected, the disorder is not inherited. With modern targeted complement inhibitor therapies, long-term survival has significantly improved, and many patients now live for decades with effective disease control.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) commonly presents with fatigue, dark or cola-colored urine, abdominal pain, dysphagia, erectile dysfunction, and life-threatening venous thrombosis, particularly in unusual sites such as hepatic, portal, and cerebral veins. Diagnosis is confirmed by flow cytometry demonstrating deficiency of CD55 and CD59 on blood cells. Modern treatment of PNH is centered on targeted complement inhibition using agents such as eculizumab, ravulizumab, and newer proximal complement inhibitors, which dramatically reduce hemolysis, transfusion dependence, and thrombotic risk.

Clinical features:

Due to the wide spectrum of symptoms associated with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), it is not unusual for months or even years to pass before the correct diagnosis is established. Overall, the most common clinical features of PNH include:

- Mild anemia of gradual onset with persistent fatigue or generalized weakness.

- Recurring infections and/or flu-like symptoms related to bone marrow dysfunction.

- Frequent urinary tract infections.

- Severe or recurrent headaches.

- Mild jaundice due to chronic intravascular hemolysis.

- Hepatosplenomegaly is common.

- Bleeding problems and easy bruising may occur secondary to thrombocytopenia.

- Abdominal pain crises and back pain.

The classic symptom of bright red blood in the urine (hemoglobinuria) occurs in 50% or fewer of patients with PNH. More commonly, patients notice that their urine becomes dark or tea-colored. Typically, hemoglobinuria is most noticeable in the morning and clears as the day progresses. Attacks of hemoglobinuria may be precipitated by infections, alcohol intake, physical exertion, emotional stress, or certain medications. Many patients experience profound fatigue that may be disabling during periods of active hemolysis. This excessive fatigue does not correlate directly with the degree of anemia and often improves as hemoglobinuria subsides.

Thromboses occur almost exclusively in veins rather than arteries and represent the leading cause of mortality in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. These thrombotic events frequently occur at unusual sites, such as the hepatic vein (causing Budd–Chiari syndrome), the portal vein (causing portal vein thrombosis), the superior or inferior mesenteric veins (causing mesenteric ischemia), and the veins of the skin. Cerebral venous thrombosis, particularly superior sagittal sinus thrombosis, is significantly more common in patients with PNH than in the general population.

Classification:

PNH is classified by the context under which it is diagnosed:

- Classical PNH: Evidence of PNH in the absence of another bone marrow disorder.

- PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder such as aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

- Subclinical PNH: in which patients have small PNH clones on flow cytometry but no clinical or laboratory evidence of hemolysis or thrombosis.

Diagnosis:

Mechanism of complement-mediated hemolysis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and inhibition by eculizumab (Soliris).

Today, the gold standard diagnostic test for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is flow cytometry analysis for CD55 and CD59 expression on both red and white blood cells. Based on the degree of deficiency of these GPI-anchored proteins, erythrocytes are classified into three populations: type I PNH cells with normal CD55 and CD59 expression, type II PNH cells with partial deficiency, and type III PNH cells with complete absence of these surface proteins. The proportion of type II and type III cells correlates with disease severity and thrombotic risk.

Fluorescein-labeled proaerolysin (FLAER testing) is now used more frequently and is considered more sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of PNH. FLAER binds directly to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor and is more accurate in detecting GPI-deficient cells than CD59 or CD55 analysis alone, particularly for identifying small PNH clones.

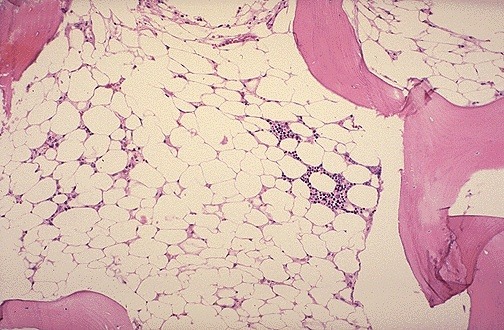

There is usually normocytic or macrocytic anemia, and neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are commonly present, especially in patients with associated bone marrow failure syndromes such as aplastic anemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

Iron deficiency is common due to chronic urinary iron loss from hemoglobinuria.

Hemoglobin and hemosiderin may be detected in the urine as a result of ongoing intravascular hemolysis.

The neutrophil alkaline phosphatase (NAP) score is typically low (as in chronic myeloid leukemia). There is increased sensitivity of red blood cells to complement-mediated lysis in acidified serum (Ham’s test), which is now of historical interest and has been largely replaced by flow cytometry and FLAER testing.

Treatment:

The appropriate treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) depends on the severity of symptoms, clone size, degree of hemolysis, thrombotic risk, and associated bone marrow failure. Some patients experience few or no symptoms and may not require specific PNH-directed therapy, aside from folic acid and occasionally iron supplementation to support red blood cell production. Over time, the disease may progress, and more aggressive supportive or targeted therapy may become necessary based on clinical evolution.

Acute attacks:

There is ongoing debate regarding the role of corticosteroids (such as prednisolone) in reducing the severity of acute hemolytic crises, and they are generally reserved for selected severe cases.

Transfusion therapy may be required for symptomatic or severe anemia; in addition to correcting anemia, transfusions may transiently suppress endogenous erythropoiesis and reduce hemolysis.

Iron deficiency commonly develops over time due to chronic urinary iron loss from hemoglobinuria and should be treated when present. However, iron replacement may paradoxically increase hemolysis by stimulating production of new GPI-deficient red cells.

Long-term treatment:

PNH is a chronic clonal stem cell disorder. In patients with small PNH clones and minimal symptoms, regular monitoring with flow cytometry every six months provides information on disease burden and thrombotic risk.

Because of the markedly increased risk of venous thrombosis in PNH, primary thromboprophylaxis with warfarin has been shown to reduce thrombotic events in selected high-risk patients, especially those with large PNH clones (≥50% type III white blood cells). Established thrombotic episodes are managed according to standard anticoagulation protocols; however, given the persistent underlying prothrombotic state in PNH, long-term or lifelong anticoagulation is often required.

N.B. Heparin may exacerbate thrombosis in some patients, possibly through complement activation. This effect can be partially mitigated by cyclooxygenase inhibitors such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and sulfinpyrazone. Medications that increase thrombotic risk, including estrogen-containing oral contraceptive pills, should be strictly avoided.

In selected cases with significant immune-mediated marrow failure, patients may respond to anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), although many will continue to require red cell and/or platelet transfusions.

Eculizumab (Soliris):

Eculizumab is a terminal complement inhibitor and a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against complement protein C5. It has revolutionized the treatment of PNH by effectively suppressing intravascular hemolysis. Eculizumab is administered intravenously at a dose of 900 mg every 2 weeks following an induction phase.

Eculizumab significantly improves quality of life, reduces transfusion requirements, decreases lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and markedly lowers the risk of thrombosis, which is now considered its most important survival benefit.

However, eculizumab does not eradicate the PNH clone and does not eliminate the long-term risk of myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, or aplastic anemia.

Eculizumab (Soliris) was the first drug approved by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European regulatory authorities for the treatment of PNH.

Eculizumab remains among the most expensive pharmaceuticals worldwide and requires meningococcal vaccination prior to initiation due to the increased risk of Neisseria infections.

Ravulizumab and newer complement inhibitors:

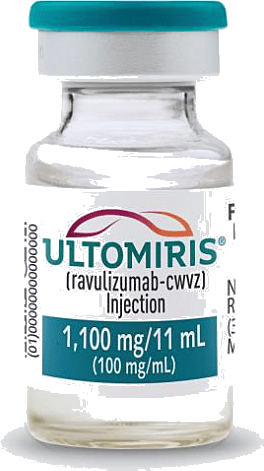

Ravulizumab is a long-acting C5 inhibitor that provides equivalent disease control to eculizumab with extended dosing intervals of every 8 weeks, improving convenience and adherence. Newer proximal complement inhibitors targeting C3, factor B, and factor D are emerging therapies and show promise in patients with extravascular hemolysis or suboptimal response to C5 blockade.

Ravulizumab (Ultomiris), a long-acting C5 complement inhibitor for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

Bone marrow transplantation:

Allogeneic (donor-derived) bone marrow transplantation (BMT) remains the only curative therapy for PNH. BMT replaces the patient’s defective stem cells with healthy donor cells, most commonly from a matched sibling donor. It is generally reserved for younger patients with severe marrow failure, transfusion-dependent cytopenias, or those who fail or cannot access complement inhibitor therapy, due to the significant morbidity and mortality associated with transplantation.

Questions and Answers:

What is paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)?

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a rare acquired clonal stem cell disorder characterized by complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis, venous thrombosis at unusual sites, and varying degrees of bone marrow failure.

What causes paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria?

PNH is caused by an acquired mutation in the PIG-A gene within a hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in deficiency of GPI-anchored protective proteins such as CD55 and CD59 on blood cells.

What are the main symptoms of PNH?

The most common symptoms of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria include chronic fatigue, dark or tea-colored urine, abdominal pain, recurrent infections, headaches, jaundice, easy bruising, and life-threatening venous thrombosis.

Why does hemoglobinuria occur in PNH?

Hemoglobinuria in PNH occurs due to uncontrolled complement activation causing intravascular destruction of red blood cells, leading to the release of free hemoglobin that is excreted in the urine.

How is paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria diagnosed?

PNH is diagnosed using flow cytometry to detect deficiency of CD55 and CD59 on red and white blood cells and by the FLAER test, which directly binds GPI-anchored proteins with high sensitivity.

What is the FLAER test in PNH?

The FLAER test is a highly sensitive flow cytometry technique that detects GPI-anchor deficiency on blood cells and is used to confirm the diagnosis of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Why is thrombosis common in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria?

Thrombosis in PNH occurs due to complement-mediated platelet activation, free hemoglobin-induced nitric oxide depletion, and endothelial dysfunction, making it the leading cause of mortality in this disease.

What are the classical sites of thrombosis in PNH?

Classical thrombotic sites in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria include the hepatic veins causing Budd–Chiari syndrome, portal vein, mesenteric veins, cerebral venous sinuses, and cutaneous veins.

What is the role of eculizumab in PNH treatment?

Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits terminal complement protein C5, effectively preventing intravascular hemolysis, reducing transfusion dependence, and lowering the risk of life-threatening thrombosis in PNH.

What is ravulizumab (Ultomiris) and how does it differ from eculizumab?

Ravulizumab is a long-acting C5 complement inhibitor that provides the same disease control as eculizumab but with extended dosing intervals every 8 weeks, improving convenience and adherence for patients with PNH.

Is paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria curable?

The only curative treatment for PNH is allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, but it is reserved for selected younger patients with severe marrow failure or refractory disease due to its high treatment-related risk.

Is PNH inherited or acquired?

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is an acquired disorder and is not inherited, despite the PIG-A gene being located on the X chromosome.

How is PNH related to aplastic anemia?

PNH has a strong association with aplastic anemia, with up to 30% of PNH cases evolving from aplastic anemia and a similar percentage developing PNH after immunosuppressive therapy.

Can patients with PNH live a normal life?

With modern complement inhibitor therapy such as eculizumab and ravulizumab, many patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria can achieve long-term disease control, improved quality of life, and significantly prolonged survival.

Why is vaccination required before starting eculizumab or ravulizumab?

Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis is mandatory before initiating complement inhibitor therapy because C5 blockade significantly increases the risk of life-threatening meningococcal infections.

References:

Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH). Available at: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/types_cancer/paroxysmal_nocturnal_hemoglobinuria_PNH.html

Hillmen, P., Young, N. S., Schubert, J., et al. (2006). The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. New England Journal of Medicine. 355: 1233–1243.

Parker, C. (2012). Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Current Opinion in Hematology. 19: 141–148.

Luzzatto, L. (2013). PNH from mutations of another PIG gene. Blood. 122(7): 1099–1100.

Martí-Carvajal, A. J., Anand, V., Cardona, A. F., Solà, I. (2014). Eculizumab for treating patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CD010340.

Hillmen, P., Kulasekararaj, A. G., Arnold, L., et al. (2019). Ravulizumab versus eculizumab in adult patients with PNH: 301 randomized phase 3 study. Blood. 133(6): 540–549.

Kulasekararaj, A. G., Hill, A., Rottinghaus, S. T., et al. (2019). Ravulizumab versus eculizumab in complement inhibitor–naïve patients with PNH: 302 randomized phase 3 study. Blood. 133(6): 530–539.

Brodsky, R. A. (2021). How I treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 137(10): 1304–1309.

Keywords:

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, PNH disease, PNH thrombosis, PNH hemoglobinuria, PNH diagnosis flow cytometry, CD55 CD59 deficiency, FLAER test PNH, complement mediated hemolysis, Budd Chiari syndrome PNH, sagittal sinus thrombosis PNH, PNH aplastic anemia, PNH treatment guidelines, eculizumab Soliris PNH, ravulizumab Ultomiris PNH, long acting C5 inhibitor, complement inhibitor therapy, PNH bone marrow failure, PNH iron deficiency, PNH transfusion dependence, PNH anticoagulation, PNH prognosis survival

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

I have a question:

Does PNH affect a man’s ability to reproduce? Specifically, his sperm?

Hello A.H.,

Thank you for reaching out.

While the condition itself does not impair sperm production or fertility, there are indirect factors to consider:

1- Medications: Some treatments for PNH, such as immunosuppressive drugs or other therapies, might have side effects that impact fertility or sexual health. For example, long-term immunosuppressive therapy can sometimes suppress overall health, which might affect reproductive capacity.

2- Anemia and Fatigue: Severe anemia, a hallmark of PNH, can cause fatigue, reduced libido, and overall weakness, which may indirectly affect sexual activity or reproductive capability.

3- Thrombosis: PNH increases the risk of thrombosis, which can impact overall vascular health. However, this is unlikely to directly impair sperm production or function unless it leads to complications affecting the reproductive organs.

4- Overall Health: If the disease is poorly managed or associated with bone marrow failure, general health and vitality might be compromised, which could indirectly influence reproductive health.

Best wishes,

Dr M Abdou