Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Lupus anticoagulant is a key antiphospholipid antibody involved in the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome and thrombotic risk assessment

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS), also known as Hughes Syndrome, is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) that promote abnormal blood clot formation (thrombosis) in both arterial and venous circulation. APS may occur as a primary condition or develop secondary to other autoimmune diseases, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Clinically, patients may present with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), stroke, pulmonary embolism, or recurrent pregnancy loss due to placental thrombosis. Persistent detection of lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies—confirmed on two or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart—forms the cornerstone of laboratory diagnosis. Early recognition and appropriate anticoagulation therapy are essential to prevent recurrent thrombotic events and improve long-term outcomes in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

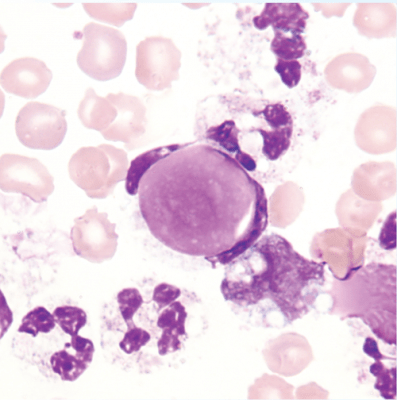

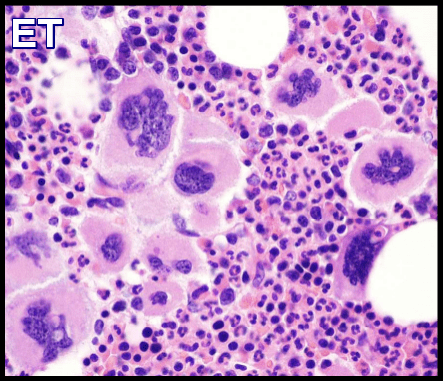

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) is an acquired, treatable autoimmune thrombophilia characterized by antiphospholipid antibodies that attack phospholipid-binding proteins such as β2-glycoprotein I, prothrombin, and annexin A5. These antibodies disrupt normal hemostasis, leading to arterial and venous thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and recurrent pregnancy loss.

APS can affect multiple organ systems, making it relevant to hematology, rheumatology, obstetrics, and cardiology. Pathophysiology involves loss of protective annexin A5 from cell membranes, exposing procoagulant surfaces that promote clot formation. In severe cases, catastrophic APS (CAPS) causes widespread microvascular thrombosis and multiorgan failure, resembling DIC, HIT, or TMA. Management includes anticoagulation, high-dose corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and biologic agents such as rituximab or eculizumab to prevent life-threatening complications.

Clinical manifestations of APS:

- Superficial and deep vein thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis, retinal vein thrombosis.

- Signs and symptoms of intracranial hypertension, pulmonary emboli, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

- Livedo reticularis.

- Arterial thrombosis – migraines, cognitive dysfunction, transient ischemic attacks, stroke, myocardial infarction, ischemic leg ulcers, digital gangrene, avascular necrosis of bone, retinal artery occlusion, renal artery stenosis, and, infarcts of spleen, pancreas, and adrenals.

- Premature atherosclerosis – a rare feature of APS.

- Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.

- Libman-Sacks endocarditis.

- The fetal loss does not appear to be explained by thrombosis, but rather seems to stem from antibody-mediated interference with the growth and differentiation of trophoblasts, leading to a failure of placentation.

- Discontinuation of therapy, major surgery, infection, and trauma may trigger Catastrophic APS.

Diagnosis:

One clinical + one laboratory criterion:

Clinical criteria:

- Vascular thrombosis in any tissue or organ.

- Pregnancy morbidity: One or more unexplained deaths of a morphologically normal fetus at or beyond the tenth week of gestation, One or more premature births of a morphologically normal neonate before the thirty-fourth week of gestation because of eclampsia, severe preeclampsia, or placental insufficiency, A 3 or more unexplained consecutive spontaneous abortions before the 10th week of gestation.

Laboratory criteria:

Characteristic laboratory abnormalities in APS include persistently elevated levels of IgG and IgM antibodies directed against membrane anionic phospholipids or their associated plasma proteins or evidence of a circulating anticoagulant.

The confirmed presence of a repeated antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies – at intermediate or high titres on two or more occasions, 12 weeks apart is a required criterion for the diagnosis of APS:

- Antibodies against cardiolipin – ACL.

- Antibodies against beta 2 glycoprotein I – B2GPI.

- Lupus anticoagulant – LA.

The lupus anticoagulant (LA) is suspected if the APTT is prolonged and does not correct immediately upon 1:1 mixing with normal plasma but does return to normal upon the addition of an excessive quantity of phospholipids (done in the clinical pathology laboratory). Antiphospholipid antibodies in patient plasma are then directly measured by immunoassays of IgG and IgM antibodies that bind to phospholipid/beta2-glycoprotein I complexes on microtiter plates.

Treatment:

The management of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is individualized and depends on the patient’s thrombotic history, antiphospholipid antibody profile, pregnancy status, and bleeding risk.

Thrombotic APS:

Patients with APS who experience a first venous thromboembolic event should receive long-term anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist, most commonly warfarin, targeting an INR of 2.0–3.0. Lifelong anticoagulation is generally recommended due to the high risk of recurrence. In patients with arterial thrombosis or recurrent thrombotic events despite standard-intensity anticoagulation, treatment may be intensified by increasing the INR target or combining warfarin with low-dose aspirin, provided bleeding risk is acceptable.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs):

Direct oral anticoagulants are not recommended in high-risk APS, particularly in patients with triple-positive antiphospholipid antibodies or those with arterial thrombosis, as studies have demonstrated higher rates of recurrent events compared with warfarin. Their use should be avoided in these groups and considered only with caution in carefully selected low-risk patients when vitamin K antagonists are unsuitable.

Obstetric APS:

Pregnancy morbidity associated with APS is best prevented using a combination of low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg daily) and prophylactic or therapeutic low-molecular-weight heparin, such as enoxaparin, throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period. Warfarin is contraindicated in pregnancy due to placental transfer and the risk of fetal bleeding, pregnancy loss, congenital anomalies, and adverse neonatal outcomes. Intravenous immunoglobulin may be considered in refractory or high-risk obstetric cases, while glucocorticoids are not routinely effective unless required for active underlying autoimmune disease.

Primary thrombosis prevention:

Low-dose aspirin may be considered in asymptomatic individuals with persistent antiphospholipid antibodies who have a high-risk antibody profile, particularly those with systemic lupus erythematosus, to reduce the risk of a first thrombotic event.

Adjunctive therapy:

Hydroxychloroquine is commonly used in patients with coexisting systemic lupus erythematosus and may provide additional antithrombotic and vascular protective benefits in APS. Management of cardiovascular risk factors, avoidance of estrogen-containing therapies, and patient education are essential components of long-term care.

Overall, treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome requires lifelong risk stratification, regular monitoring, and close collaboration between hematology, rheumatology, obstetric, and primary care teams to optimize outcomes and minimize complications.

Summary:

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), also known as Hughes syndrome or “sticky blood syndrome,” is an acquired autoimmune thrombophilia characterized by persistent antiphospholipid antibodies that promote abnormal blood clot formation. These antibodies—most commonly lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I—interfere with normal coagulation pathways, leading to arterial and venous thrombosis as well as pregnancy-related complications. Clinically, antiphospholipid syndrome is associated with deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, recurrent pregnancy loss, pre-eclampsia, and placental insufficiency. APS may occur as a primary condition or secondary to autoimmune diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus. First described in the 1980s by Dr. Graham Hughes, antiphospholipid syndrome has no definitive cure; however, long-term management with anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy significantly reduces thrombotic risk and improves clinical outcomes when appropriately monitored.

Questions and Answers:

What is antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)?

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by persistent antiphospholipid antibodies that increase the risk of abnormal blood clot formation in veins and arteries, leading to thrombosis and pregnancy complications.

What antibodies are involved in antiphospholipid syndrome?

The main antibodies involved in antiphospholipid syndrome are lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies, which interfere with normal coagulation mechanisms.

What is lupus anticoagulant and why is it important in APS?

Lupus anticoagulant is an antiphospholipid antibody that paradoxically prolongs clotting tests in vitro while increasing the risk of thrombosis in vivo, making it a key marker for diagnosing high-risk antiphospholipid syndrome.

What are the common symptoms of antiphospholipid syndrome?

Common manifestations include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, recurrent miscarriages, livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia, and heart valve abnormalities.

What causes livedo reticularis in antiphospholipid syndrome?

Livedo reticularis in antiphospholipid syndrome results from impaired blood flow in small dermal vessels due to antibody-mediated thrombosis and vascular dysfunction, producing a characteristic mottled skin pattern.

What is Libman-Sacks endocarditis and how is it related to APS?

Libman-Sacks endocarditis is a form of non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis characterized by sterile valvular vegetations, commonly associated with antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus.

How is antiphospholipid syndrome diagnosed?

Diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome requires both clinical criteria, such as thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity, and persistent laboratory positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies on two occasions at least 12 weeks apart.

Can antiphospholipid syndrome cause recurrent miscarriage?

Yes, antiphospholipid syndrome is a leading treatable cause of recurrent pregnancy loss due to placental thrombosis and impaired placental blood flow.

What is the best treatment for antiphospholipid syndrome?

Treatment depends on clinical presentation but typically involves long-term anticoagulation with warfarin for thrombotic APS and a combination of low-dose aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin during pregnancy.

Are direct oral anticoagulants safe in antiphospholipid syndrome?

Direct oral anticoagulants are not recommended in high-risk antiphospholipid syndrome, particularly in patients with triple-positive antibodies or arterial thrombosis, due to increased recurrence rates compared with warfarin.

Is antiphospholipid syndrome curable?

Antiphospholipid syndrome has no definitive cure, but appropriate long-term treatment and risk factor control significantly reduce thrombotic complications and improve long-term outcomes.

References:

Moake JL. Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (APS). MSD Manual Professional Edition. Available at: https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/hematology-and-oncology/thrombotic-disorders/antiphospholipid-antibody-syndrome-aps

Nayfe R, Uthman I, Aoun J, et al. Seronegative antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(8):1358–1367. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/52/8/1358/1790830

El-Gaby O. Are there evidence-based strategies in the treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy? MSc Dissertation, Rheumatology Department, Hammersmith Hospital, University of London; 2010.

Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, Indiveri F, Puppo F. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16(4):395–408. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0425-7

Better Health Channel. Hughes syndrome (Antiphospholipid Syndrome). Victorian State Government. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/hughes-syndrome

Khamashta MA, Cuadrado MJ, Mujic F, Taub NA, Hunt BJ, Hughes GRV. The management of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(15):993–997. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504133321504

Crowther MA, Ginsberg JS, Julian J, et al. A comparison of two intensities of warfarin for the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1133–1138. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035241

Pengo V, Denas G, Zoppellaro G, et al. Rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (TRAPS trial). Blood. 2018;132(13):1365–1371. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-04-848333

Devreese KMJ, Ortel TL, Pengo V, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(10):1296–1304. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

Erkan D, Lockshin MD. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. Last updated 2024.

StatPearls Publishing. Antiphospholipid Syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430980/

Mayo Clinic. Antiphospholipid syndrome: symptoms and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/antiphospholipid-syndrome

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Antiphospholipid Syndrome. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/antiphospholipid-syndrome

Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77(3):195–207. doi:10.1097/00005792-199805000-00003

Erkan D, Vega J, Ramón G, Kozora E, Lockshin MD. Rituximab for non-criteria manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):464–471. doi:10.1002/art.37796

Keywords:

antiphospholipid syndrome, APS, Hughes syndrome, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I, β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, APS diagnosis, APS diagnostic criteria, APS laboratory tests, APS treatment, APS management guidelines, APS anticoagulation therapy, APS warfarin treatment, APS INR target, APS direct oral anticoagulants, APS DOACs risk, APS rivaroxaban trial, APS pregnancy complications, obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome, APS recurrent miscarriage, APS placental thrombosis, APS and pregnancy treatment, APS thrombosis, APS venous thrombosis, APS arterial thrombosis, APS stroke, APS myocardial infarction, APS deep vein thrombosis, APS pulmonary embolism, APS thrombocytopenia, APS livedo reticularis, APS Libman-Sacks endocarditis, APS cardiac involvement, APS and lupus, APS secondary to SLE, primary antiphospholipid syndrome, seronegative antiphospholipid syndrome, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, CAPS management, APS hydroxychloroquine, APS biologic therapy, rituximab antiphospholipid syndrome, APS prognosis, APS long-term management, APS patient education, EULAR antiphospholipid syndrome guidelines, Ask Hematologist antiphospholipid syndrome, Dr Moustafa Abdou hematology articles

Hello,

My daughter is 15. She is constantly tired and sleeps 13-14 hours a day. She gets headache, dizziness sometimes, also chest pains and shortness of breath.

She is slightly low on iron but not anemic.

My concern is her APTT is 34.4 (22.1-27.6), platelets are 444 (150-400). She has not been tested for lupus anticoagulant or other factor deficiency. Anticardiolipin IgG and IGM were negative. I’m really concern. Please help if you can.

Hi Sangita,

Thank you for your comment.

I would suggest checking her Lupus Anticoagulant, Factor 8, CRP, and liver functions.

BW,

Hello Doctor,

Thank you for your reply. We checked and she has lupus anticoagulant detected in her blood. She also has DRVVT test ratio 1.43 (0.80-1.20), Ratio correction 27.3 (0-10.0),DRVVT corrected ratio 1.23 (0.80-1.20) APTT 30.5 (22.1-27.6), platelets were 444, calcium 2.61(2.20-2.60), albumin 53(32-45).

INR 0.97(0.9-1.2)

With her symptoms of shortness of breath and chest pain, palpitations, some headaches and dizziness. I’m very sure her symptoms are from antiphospholipid syndrome. Paediatrician was not concerned and says she is clinical stable, but I am a pharmacist and I know these symptoms , however intermittent, can not be ignored and she is far from stable.

Would you please let me know your thought.

Many Thanks in advance

I just tested positive for lupus anticoagulant and I also have Lupus SLE. I asked my rheumatologist to run the test after a left hip AVN as I suspect a blood clotting disorder may be the culprit. My rheumatologist advises I simply take a low dose baby aspirin. Should I follow up with my hematologist for further testing and treatment?

Hi Lisa,

Thank you for your comment.

You haven’t mentioned if you had any previous blood clots and/or miscarriages or not?

However, I would agree with your rheumatologist to keep on a low dose Aspirin (75mg once daily) and to check your blood for:

*Antibodies against Cardiolipin – ACL.

*Antibodies against beta 2 glycoprotein I – B2GPI.

* And to repeat the Lupus anticoagulant test – LA.

BW,

Hello Doctor,

I was diagnosed with APS 13 yrs ago when I had a stillbirth. I am concerned if the COVID vaccines (which utilize the spike protein) would put me at risk for clotting from the vaccine. Many papers are pointing to activation of ACL from covid with clotting as a result. I know the spike protein elicits the immune response but will it elicit clotting with APS. the EU is investigating the Astrazeneca vaccine due to morbidities in some with clotting. Not sure where to go from here. I don’t have a hematologist and have been healthy since my APS was transient. Please advise.

thank you

Hi Rebecca,

Thanks for your comment.

The dilemma around COVID 19 vaccines and their possible side effects are still ongoing and no one can tell you with confidence their long-term sequences. However, if you don’t have any previous thromboembolic events and you are on Aspirin it would be logical to get vaccinated.

BW,

Dr. Abdou:

This site is a great resource, thank you!

Coincidentally a couple days after my first Covid-19 vaccine (Moderna), I saw a rheumatologist to investigate my ongoing chronic myalgia. He did a comprehensive workup that included tests for antiphospholid antibodies – my B2GP1 IGG antibodies were very elevated (196 CU), all other antibodies normal. Follow-up testing 3 months later (2 months after my second vaccine) showed these antibodies had fallen back to reference range (<6 CU).

The rheumatologist brushed off my question about the vaccine possibly being responsible, but given the timing and known instances of certain vaccines and some illnesses (including Covid-19) causing transient increases in antiphospholid antibodies, I find it hard to believe this was just a coincidence. I've also seen a couple of recent articles in the literature acknowledging a possible link and calling for further research (Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;60:52-60. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.05.001 and Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021;5(3):rkab096. Published 2021 Dec 1. doi:10.1093/rap/rkab096).

Even though I didn't have any known events at that time, my understanding is that a high-level of those antibodies is in and of itself a risk factor for developing clots. I'm far from an antivaxxer, but this certainly gives me pause when considering whether or not to get a booster shot.

Hi Jordan,

Many thanks for your comment and your kind words on my website.

It is not clear from your comment whether you had a full antiphospholipid screen including the lupus anticoagulant and cardiolipin antibodies or just the B2GP1 IgG and IgM antibodies? We still don’t know too much about the short and long-term complications of the Coronavirus and the available vaccinations for it but blood clots are mainly linked to the AstraZeneca Vaccine rather than to Moderna. I agree with you that your first high B2GP1 IgG reading could be reactive but I would suggest having another full antiphospholipid screen as part of investigating your ongoing chronic myalgia and going ahead with your booster dose of COVID-19 vaccination (likely Pfizer) regardless of the result of the antiphospholipid screen in view of the rapidly spreading Omicron variant.

BW,

I tested positive 12 weeks apart for the antiphospholipid antibody. My rheumatologist said unless an event occurs to not take baby aspirin or get on a blood thinner. I had 2 miscarriages about 14 years ago I believe they were before 10 weeks. Is this the best course of action or should I see a hematologist about taking something. Thanks!

Hi Jenni,

Thank you for reaching out.

Have you experienced any thromboembolic events before or do you have a family history of blood clots?

If you are considering having a baby, it is important to discuss with your treating doctor regarding your Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) treatment plan.

Treatment during pregnancy typically includes daily doses of baby aspirin and low molecular weight heparin.

I recommend consulting with a hematologist for further guidance.

Best regards,

Dr. M Abdou