Anemias-General Approach

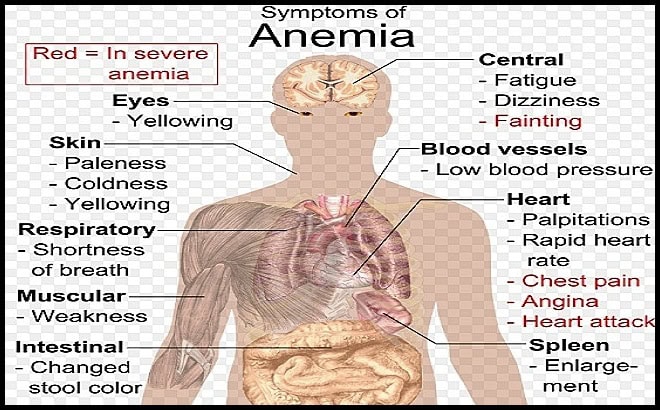

Common anemia symptoms including fatigue, weakness, reduced concentration, and dizziness due to impaired oxygen delivery to body tissues.

Anemia is a common hematological condition characterized by a reduction in circulating red blood cells or hemoglobin (Hb), resulting in impaired oxygen delivery to body tissues. It is not a diagnosis in itself but rather a clinical manifestation of an underlying disorder; therefore, even mild or asymptomatic anemia warrants proper evaluation to identify and treat the primary cause.

When anemia develops gradually, symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific, commonly including fatigue, generalized weakness, reduced exercise tolerance, and exertional dyspnea. In contrast, acute-onset anemia is typically associated with more pronounced manifestations such as dizziness, confusion, presyncope or syncope, loss of consciousness, and increased thirst, reflecting rapid compromise in oxygen delivery. Clinical pallor usually becomes evident only when anemia is moderate to severe, and additional symptoms may arise depending on the underlying etiology, highlighting the importance of a systematic diagnostic approach.

Diagram illustrating common systemic symptoms and clinical features of anemia affecting the central nervous system, cardiovascular system, skin, respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, muscles, and spleen.

Anemia may be acute or chronic and can range in severity from mild to life-threatening. Because anemia is often a marker of underlying pathology, medical evaluation is essential whenever it is suspected, as it may indicate serious systemic disease.

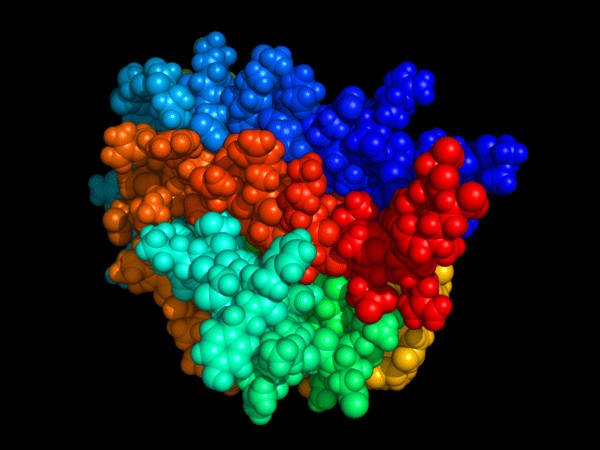

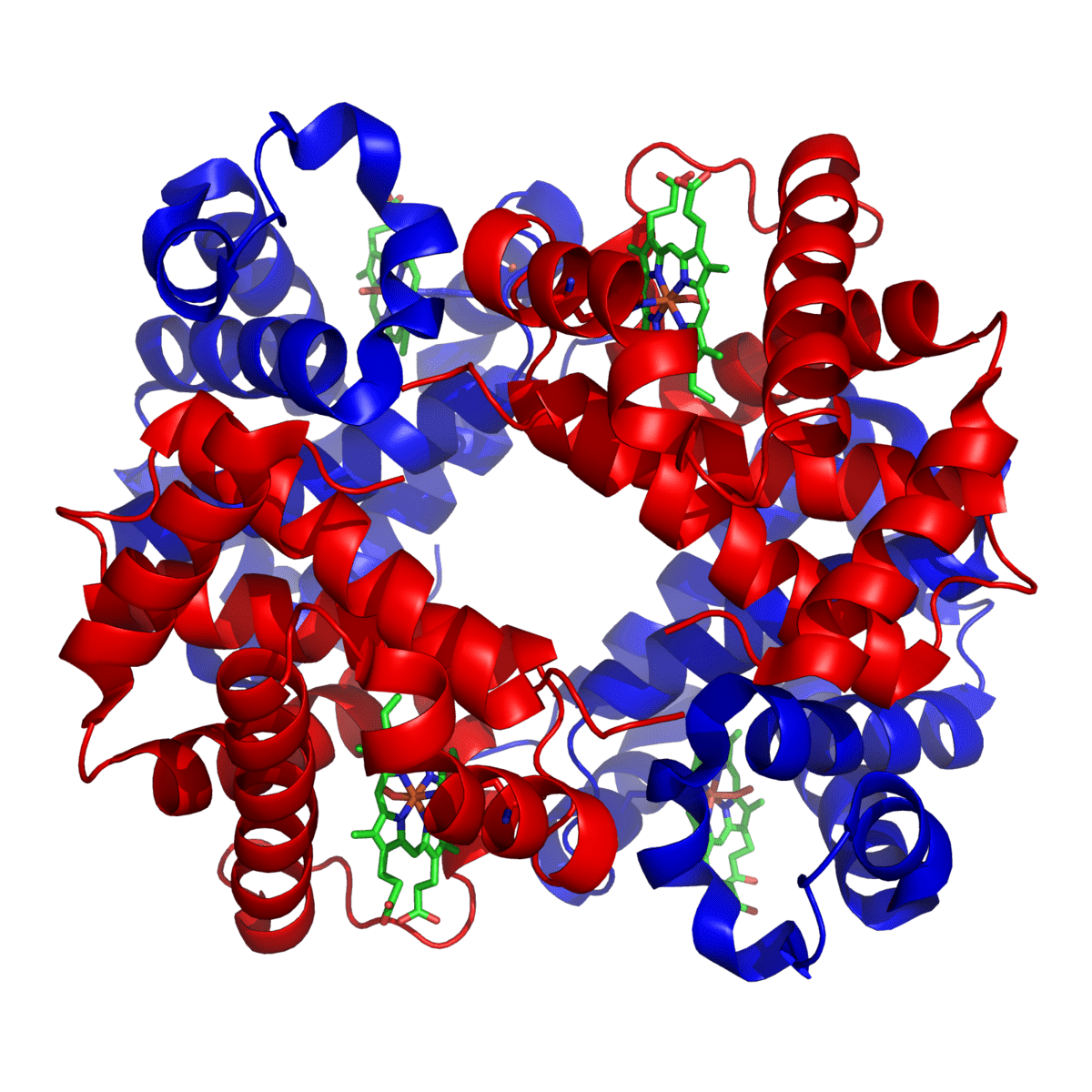

From a pathophysiological perspective, anemia is broadly classified into three main categories: anemia due to blood loss, anemia due to decreased red blood cell production by the bone marrow, and anemia due to increased red blood cell destruction (hemolysis). Causes of blood loss include trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, menorrhagia, and other sources of acute or chronic hemorrhage. Reduced red blood cell production commonly results from iron deficiency, vitamin B12 and/or folate deficiency, thalassemia syndromes, anemia of chronic disease, and bone marrow disorders including hematologic malignancies. Increased red blood cell destruction may occur in inherited hemolytic anemias such as sickle cell disease, in infectious conditions such as malaria, and in immune-mediated hemolytic processes.

Anemia can also be classified morphologically based on red blood cell size and hemoglobin content into microcytic, normocytic, and macrocytic anemia, a distinction that provides important diagnostic clues. Serum iron levels are typically reduced in iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic inflammation but are normal or elevated in thalassemia syndromes, hemoglobin E disorders, and lead toxicity.

Diagnostic thresholds for anemia vary by sex and age: in adult men, anemia is defined as hemoglobin < 14 g/dL, hematocrit < 42%, or red blood cell count < 4.5 million/μL, while in adult women it is defined as hemoglobin < 12 g/dL, hematocrit < 37%, or red blood cell count < 4 million/μL; in infants and children, normal values are age-dependent and must be interpreted using appropriate reference ranges.

| Age group | Hemoglobin (g/dL) | Hematocrit (%) | RBC (×1012/L) | MCV (fL) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn 0–24 hours |

14–22 | 45–65 | 4.0–6.6 | 98–118 | Higher Hb/Hct at birth; falls physiologically over weeks. |

| Neonate 1 week |

13–20 | 42–60 | 3.9–6.3 | 95–115 | Transition period; interpret with local neonatal ranges. |

| Infant 1 month |

10–18 | 31–55 | 3.2–5.4 | 85–105 | Physiologic anemia of infancy may be seen around 6–12 weeks. |

| Infant 2 months |

9–14 | 28–42 | 3.1–4.8 | 77–95 | Expected Hb nadir in many infants (timing varies). |

| Infant 3–6 months |

10–14 | 30–40 | 3.5–5.0 | 74–90 | Iron status becomes increasingly important after ~4–6 months. |

| Toddler 6–24 months |

10.5–13.5 | 33–39 | 3.7–5.3 | 70–86 | Common age for iron deficiency; consider ferritin/CRP when indicated. |

| Child 2–6 years |

11.5–13.5 | 34–40 | 3.9–5.3 | 75–87 | Use age-adjusted thresholds rather than adult cutoffs. |

| Child 6–12 years |

11.5–15.5 | 35–45 | 4.0–5.4 | 77–95 | Broader “normal” range; interpret in clinical context. |

| Adolescent 12–18 years |

♀ 12–16 ♂ 13–17 |

♀ 36–46 ♂ 38–50 |

♀ 4.0–5.2 ♂ 4.2–5.8 |

78–98 | Sex-specific differences emerge after puberty. |

Note: These are typical pediatric reference intervals for educational use. Always use your local laboratory’s age- and sex-specific reference ranges (and consider prematurity, altitude, and assay methodology).

Once anemia is identified, further targeted investigations are required to establish the underlying cause and guide appropriate management.

Diagnosis:

The initial evaluation of anemia relies on a set of basic blood investigations aimed at defining the severity, mechanism, and underlying cause. These include a complete blood count (CBC) with white blood cell and platelet counts, red blood cell indices and morphology, reticulocyte count, and peripheral blood smear examination.

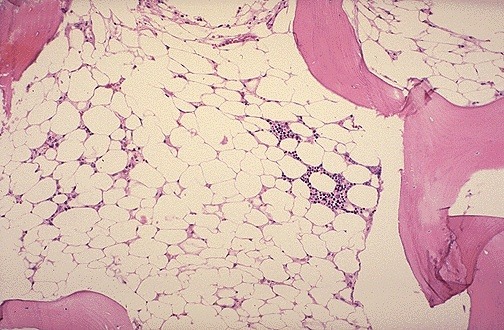

Biochemical tests commonly include serum iron studies (serum iron and ferritin), vitamin B12 and folate levels, serum bilirubin (total and direct), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to assess for hemolysis. In selected cases, particularly when bone marrow failure, infiltrative disease, or unexplained cytopenias are suspected, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis.

Preventive supplementation with iron and folic acid is beneficial in specific high-risk groups, such as pregnant women, where deficiency is common; however, empirical dietary supplementation without identifying the underlying cause of anemia is generally discouraged. Management decisions, particularly regarding blood transfusion, are guided primarily by clinical symptoms and hemodynamic status rather than hemoglobin levels alone. In asymptomatic individuals, red blood cell transfusion is usually not indicated unless hemoglobin levels fall below approximately 6–8 g/dL, whereas transfusion may be warranted at higher levels in the setting of acute blood loss or cardiovascular compromise. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents are reserved for selected patients with severe chronic anemia and specific indications.

Globally, anemia remains the most common hematologic disorder, affecting nearly one quarter of the world’s population, with iron-deficiency anemia alone impacting close to one billion individuals. Each major type of anemia will be addressed individually in subsequent sections to provide a focused and detailed discussion of their diagnosis and management.

Educational Video: Hematology Mnemonics for Anemia

Questions and Answers:

What is anemia in simple terms?

Anemia is a condition in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to low hemoglobin levels or a decreased number of red blood cells, leading to symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

Why is anemia considered a sign rather than a diagnosis?

Anemia reflects an underlying disorder such as nutritional deficiency, blood loss, bone marrow disease, or hemolysis, and identifying the cause is essential for appropriate treatment.

What are the main types of anemia based on mechanism?

Anemia is broadly classified into anemia due to blood loss, decreased red blood cell production by the bone marrow, and increased red blood cell destruction known as hemolysis.

How does MCV help in the classification of anemia?

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) classifies anemia into microcytic, normocytic, or macrocytic types, providing an important diagnostic framework to guide further investigations.

What are common causes of microcytic anemia?

Microcytic anemia is most commonly caused by iron deficiency but may also result from thalassemia, anemia of chronic disease, sideroblastic anemia, or lead toxicity.

What blood tests are essential in the initial evaluation of anemia?

Key investigations include a complete blood count with indices, reticulocyte count, peripheral blood smear, iron studies, vitamin B12 and folate levels, bilirubin, and LDH.

Why is the reticulocyte count important in anemia assessment?

The reticulocyte count indicates bone marrow response and helps differentiate between anemia caused by decreased production and anemia due to blood loss or hemolysis.

What is the Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) and when is it used in anemia investigations?

The Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT), also known as the direct Coombs test, detects antibodies or complement bound to red blood cells and is used when immune-mediated hemolysis is suspected, supporting the diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, drug-induced hemolysis, or transfusion reactions.

When is bone marrow examination required in anemia?

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are indicated when anemia is unexplained, associated with other cytopenias, or when bone marrow failure or infiltration is suspected.

How do anemia symptoms differ between acute and chronic cases?

Chronic anemia often presents with vague symptoms such as fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance, while acute anemia may cause dizziness, syncope, confusion, or hemodynamic instability.

At what hemoglobin level is blood transfusion recommended?

In asymptomatic patients, transfusion is generally not recommended unless hemoglobin levels fall below 6–8 g/dL, though higher thresholds may apply in acute bleeding or cardiovascular disease.

Why is empirical iron supplementation discouraged?

Empirical supplementation without identifying the cause of anemia may delay diagnosis of serious conditions and lead to inappropriate or harmful treatment.

Which populations benefit from preventive iron and folic acid supplementation?

Pregnant women and other high-risk groups may benefit from preventive supplementation due to increased physiological demands and higher risk of deficiency.

How common is anemia worldwide?

Anemia is the most common blood disorder globally, affecting approximately one quarter of the world’s population.

How prevalent is iron-deficiency anemia?

Iron-deficiency anemia affects nearly one billion people worldwide and remains the leading cause of anemia across all age groups.

How can mnemonics help in understanding anemia?

Hematology mnemonics simplify complex concepts, improve recall of anemia classifications and causes, and are particularly useful for medical students and clinicians during exams and clinical practice.

References:

Braunstein EM. Evaluation of Anemia. Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Hematology and Oncology.

Available at: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/approach-to-the-patient-with-anemia/evaluation-of-anemia

Brown RG. Determining the cause of anemia: General approach, with emphasis on microcytic hypochromic anemias. Postgraduate Medicine. 1990;87(1):135–142.

Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2020645/

Hillman RS, Ault KA, Rinder HM. Approach to the patient with anemia. In: Hematology in Clinical Practice. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Means RT Jr. Anemia: General considerations. In: Williams Hematology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

Hoffbrand AV, Moss PAH. Anemias. In: Essential Haematology. 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016.

World Health Organization (WHO). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005: WHO global database on anaemia. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

Keywords:

anemia general approach, anemia diagnosis, anemia evaluation, causes of anemia, types of anemia, anemia classification, microcytic anemia, macrocytic anemia, normocytic anemia, iron deficiency anemia, anemia of chronic disease, hemolytic anemia, anemia blood tests, CBC anemia interpretation, reticulocyte count anemia, peripheral blood smear anemia, DAT test anemia, direct antiglobulin test anemia, bone marrow biopsy anemia, anemia symptoms fatigue pallor, acute anemia vs chronic anemia, anemia transfusion threshold, erythropoiesis stimulating agents anemia, anemia in pregnancy, global prevalence of anemia, iron deficiency worldwide, hematology anemia guide, anemia for medical students, anemia mnemonics, anemia clinical approach