Malaria

Malaria is due to infection with specific protozoa of the Plasmodium genus. It is transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles mosquito. The malaria parasite undergoes a single sexual cycle in the mosquito and recurrent asexual cycles, with the production of sexual forms (gametocytes) in man.

Clinical features:

- The initial incubation period of malaria is 9-11 days.

- Malaria symptoms include fever, shaking chills, body aches, cough, headache, anemia, fatigue, malaise, and splenomegaly. The fever is often periodic, the frequency in part reflecting the species of Plasmodium.

- In severe cases especially of the malignant tertian form (P. falciparum), there may be hemolysis, thromboses, shock, and cerebral complications.

It was demonstrated in the late eighties and early nineties that those with O type blood group are protected from severe or fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria compared with non-O blood groups (A, B, and AB) by the mechanism of inducing high levels of anti-malarial IgG antibodies.

Investigations:

During an acute episode of malaria, there may be anemia and plasmodial forms can be detected in the peripheral blood especially on thick and thin blood films. Differentiation of the different species require considerable expertise but is important as together with the geographical source of origin, this will influence the choice of therapy. Note that 1 negative smear does not exclude malaria as a diagnosis; several more smears should be examined over a 36-hour period.

Specific tests for malaria infection should be also carried out e.g. Microhematocrit centrifugation and Fluorescent dyes/ultraviolet indicator tests.

Fewer than 5% of malaria patients have leucocytosis; thus, if leucocytosis is present, the differential diagnosis should be broadened!

If the patient is to be treated with primaquine, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) level should be checked.

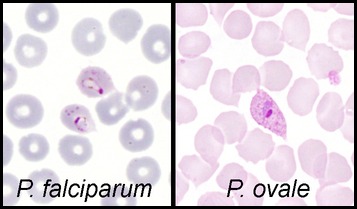

Plasmodium Falciparum

Parasites may be scanty, but red cells super-infected with trophozoites may be seen. Infected RBCs are round, of normal size and Schuffner’s dots are not seen. The gametocytes are typically elongated or banana-shaped.

Plasmodium Vivax

Ring forms (trophozoites) and segmented schizonts may be seen. The schizonts may develop into free merozoites or into round sexual forms (gametocytes).

The invaded red cells are increased in size and contain Schuffner’s dots.

Plasmodium Ovale

The appearances in the blood are similar to Plasmodium Vivax except that the gametocytes and infected red cells are often oval with fimbriated edges. Schuffner’s dots are conspicuous.

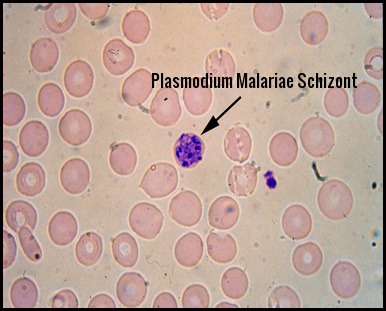

Plasmodium Malariae

In this form, the trophozoites are often band-shaped. The infested red cells are not enlarged and there are no Schuffner’s dots.

N.B. It should be noted that mixed infections can occur.

Prophylaxis:

Blood type, metabolism, exercise, shirt color and even drinking beer can make individuals especially delicious to mosquitoes! Mosquitoes bite us to harvest proteins from our blood—research shows that they find certain blood types more appetizing than others. One study found that in a controlled setting, mosquitoes landed on people with Type O blood nearly twice as often as those with Type A. People with Type B blood fell somewhere in the middle of this itchy spectrum. Additionally, based on other genes, about 85 percent of people secrete a chemical signal through their skin that indicates which blood type they have, while 15 percent do not, and mosquitoes are also more attracted to secretors than nonsecretors regardless of which type they are.

Prophylaxis involves mosquito control, avoidance of bites and appropriate prophylactic drug therapy. Avoid mosquitoes by limiting exposure during times of typical blood meals (ie, dawn, dusk). Wearing long-sleeved clothing and using insect repellants may also prevent infection. Avoid wearing perfumes and colognes.

Considerations when choosing a drug for malaria prophylaxis:

- Recommendations for drugs to prevent malaria differ by country of travel and can be found in the country-specific tables of the Yellow Book. Recommended drugs for each country are listed in alphabetical order and have comparable efficacy in that country.

- No antimalarial drug is 100% protective and must be combined with the use of personal protective measures, (i.e., insect repellent, long sleeves, long pants, sleeping in a mosquito-free setting or using an insecticide-treated bednet).

- For all medicines, also consider the possibility of drug-drug interactions with other medicines that the person might be taking as well as other medical contraindications, such as drug allergies.

- When several different drugs are recommended for an area, the following information might help in the decision process:

Atovaquone/Proguanil (Malarone):

Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Some people prefer to take daily medicine.

Good choice for shorter trips because you only have to take the medicine for 7 days after traveling rather than 4 weeks. Very well-tolerated medicine – side effects uncommon.

Pediatric tablets are available and may be more convenient. However, cannot be used by women who are pregnant or breastfeeding a child less than 5 kg, cannot be taken by people with severe renal impairment, tends to be more expensive than some of the other options (especially for trips of long duration). Some people (including children) would rather not take medicine every day.

Chloroquine:

Some people would rather take medicine weekly. Good choice for long trips because it is taken only weekly. Some people are already taking hydroxychloroquine chronically for rheumatologic conditions. In those instances, they may not have to take additional medicine. Can be used in all trimesters of pregnancy. However, cannot be used in areas with chloroquine or mefloquine resistance, may exacerbate psoriasis. Some people would rather not take a weekly medication. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel. Not a good choice for last-minute travelers because drug needs to be started 1-2 weeks prior to travel.

Doxycycline:

Some people prefer to take daily medicine. Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Tends to be the least expensive antimalarial. Some people are already taking doxycycline chronically for prevention of acne. In those instances, they do not have to take additional medicine. Doxycycline also can prevent some additional infections (e.g., Rickettsiae and leptospirosis) and so it may be preferred by people planning to do lots of hiking, camping, and wading and swimming in freshwater. However, cannot be used by pregnant women and children <8 years old. Some people would rather not take medicine every day. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel. Women prone to getting vaginal yeast infections when taking antibiotics may prefer taking a different medicine. Persons planning on considerable sun exposure may want to avoid the increased risk of sun sensitivity. Some people are concerned about the potential of getting an upset stomach from doxycycline.

Mefloquine (Lariam):

Some people would rather take medicine weekly. Good choice for long trips because it is taken only weekly. Can be used during pregnancy. However, cannot be used in areas with mefloquine resistance. Cannot be used in patients with certain psychiatric conditions. Cannot be used in patients with a seizure disorder. Not recommended for persons with cardiac conduction abnormalities. Not a good choice for last-minute travelers because the drug needs to be started at least 2 weeks prior to travel. Some people would rather not take a weekly medication. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel.

Primaquine:

It is the most effective medicine for preventing P. vivax and so it is a good choice for travel to places with > 90% P. vivax. Good choice for shorter trips because you only have to take the medicine for 7 days after traveling rather than 4 weeks. Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Some people prefer to take daily medicine. However, cannot be used in patients with glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Cannot be used in patients who have not been tested for G6PD deficiency. There are costs and delays associated with getting a G6PD test done; however, it only has to be done once. Once a normal G6PD level is verified and documented, the test does not have to be repeated the next time primaquine is considered. Cannot be used by pregnant women. Cannot be used by women who are breastfeeding unless the infant has also been tested for G6PD deficiency. Some people (including children) would rather not take medicine every day. Some people are concerned about the potential of getting an upset stomach from primaquine.

Treatment:

Consider malaria in every febrile patient returning from a malaria-endemic area within the last year, especially in the previous three months, regardless of whether they have taken chemoprophylaxis, as prompt recognition and appropriate treatment will improve prognosis and prevent deaths. Failure to consider malaria in the differential diagnosis of febrile illness in a patient who has traveled to an area where malaria is endemic can result in significant morbidity or mortality, especially in children and in pregnant or immunocompromised patients.

Malaria treatment:

- Rest and fluids are required during the acute phase.

- Drugs are given to eradicate the asexual blood-borne cycle and the exoerythrocytic (liver) parasites “doesn’t occur with P. falciparum”.

- Several groups of drugs are available and the correct drug should be chosen by an expert.

- Generally speaking, P. falciparum is resistant to Chloroquine treatment. Resistance is rare in P. vivax infection, and P. ovale and P. malariae remain sensitive to chloroquine. Primaquine is required in the treatment of P. ovale and P. vivax infection in order to eliminate the exoerythrocytic (liver) parasites.

References:

Kobayashi T, Gamboa D, Ndiaye D, et al; Malaria Diagnosis Across the International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research: Platforms, Performance, and Standardization. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Sep 93(3 Suppl):99-109. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0004. Epub 2015 Aug 10.

Smith AD, Bradley DJ, Smith V, et al; Imported malaria and high risk groups: observational study using UK surveillance data 1987-2006. BMJ. 2008 Jul 3 337:a120. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a120.

Day N (2008). Malaria. In M Eddleston et al., eds., Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine, 3rd ed., pp. 31-65. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE (2010). Plasmodium species (malaria). In GL Mandell et al., eds., Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 7th ed., vol. 2, pp. 3437-3462. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

American Public Health Association (2008). Malaria. In DL Heymann, ed., Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, 19th ed., pp. 373-393. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

Choosing a Drug to Prevent Malaria. Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and malaria. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/drugs.html reviewed: November 9, 2012.

Nasr A, Eltoum M, Yassin A, ElGhazali G. Blood group O protects against complicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria by the mechanism of inducing high levels of anti-malarial IgG antibodies – Saudi J Health Sci https://goo.gl/7SW1TJ

Joseph Stromberg. Why Do Mosquitoes Bite Some People More Than Others? https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-do-mosquitoes-bite-some-people-more-than-others-10255934/