Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), also known as acute myelogenous leukemia, is an aggressive hematologic malignancy characterized by clonal proliferation of immature myeloid precursor cells in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and occasionally extramedullary tissues. This uncontrolled expansion results in suppression of normal hematopoiesis due to maturation arrest at an early stage of myeloid differentiation. AML is typically diagnosed when myeloblasts constitute 20% or more of nucleated cells in the bone marrow or peripheral blood, distinguishing it from myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative neoplasms. The disease predominantly affects middle-aged and older adults, although it can occur at any age. Given its rapid clinical progression, early recognition and prompt initiation of appropriate, risk-adapted therapy are essential to improve survival outcomes. The ICD-10 code for acute myeloid leukemia (C92.00) is used for accurate diagnosis, classification, treatment planning, and reimbursement.

Clinical Features:

Although the onset is usually acute there is a smouldering or “preleukemic” phase in about 15% of cases.

The presenting features of AML, as in ALL, are generally those of bone marrow failure:

Anemia with weakness and lethargy.

Leucopenia with recurrent infections.

Thrombocytopenia with purpura and bleeding. Bleeding may be particularly severe in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL/M3) in which disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a feature.

Hepatosplenomegaly but not lymphadenopathy is common.

Infiltration of the gums and perineum is a feature of AML, particularly M4 and M5.

Investigations:

- FBC & Blood film.

- Coagulation profile.

- Biochemistry profile including U&Es, LFTs, Bone, LDH, Uric Acid and hematinics.

- CXR.

- CT scan neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis.

- ECG.

- Echocardiogram.

- Cultures, in particular blood cultures.

- Bone marrow aspirate, trephine, cell markers and cytogenetics.

Anemia is usually present. Anisocytosis and poikilocytosis are common.

The total leucocyte count is usually raised with myeloblasts the predominant cell type. The neutrophil count is usually reduced.

The platelet count is usually low.

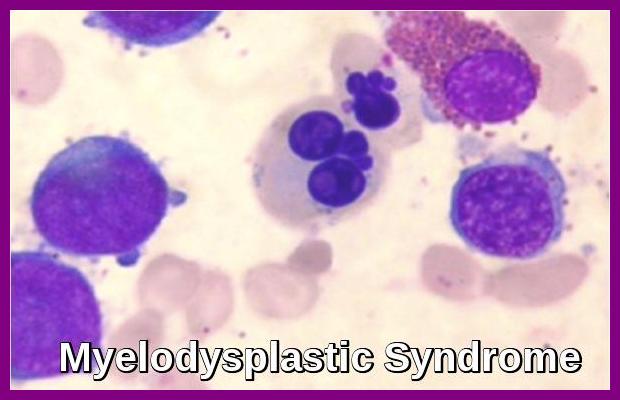

The bone marrow is hypercellular and aspiration may be difficult. Blast cells predominate. Features of dyserythropoiesis and dysgranulopoiesis are seen.

In the “preleukemic phase” there is depression of one or more cell lines in the blood with few if any blast cells present. In the marrow, there is usually marked dyshematopoiesis and there may or may not be a modest increase in blast cells. Ringed sideroblasts may be seen on iron stains.

Diagnosis:

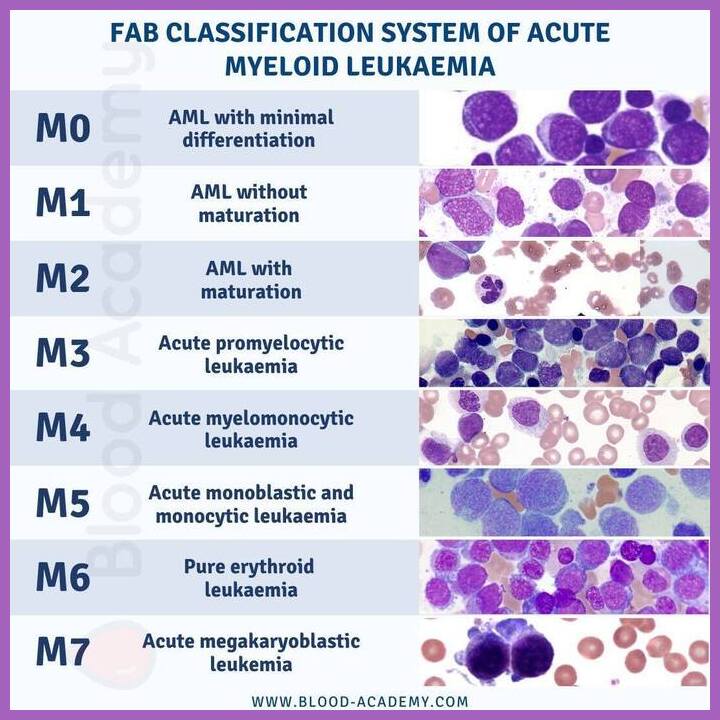

Morphology is the gold standard for blast enumeration with a blast percentage of 20% defining AML in the WHO classification system. Of note, a blast percentage of 30% was used by the FAB classification.

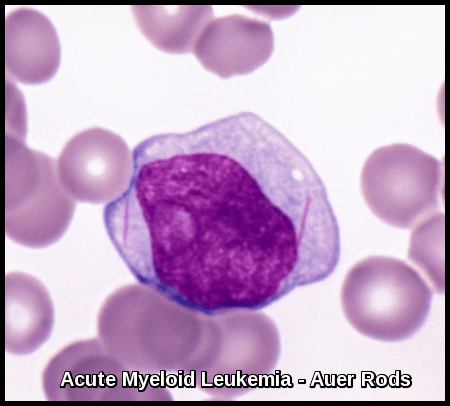

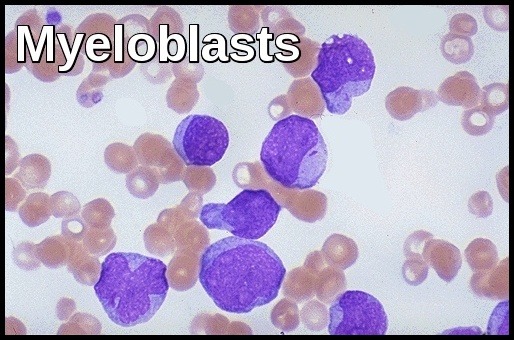

Myeloblasts vary in size but are usually intermediate or large cells with relatively abundant blue cytoplasm. The nuclear chromatin is finely dispersed with often more than two nucleoli per cell. The finding of “Auer Rods” is pathognomonic of AML.

Monoblasts are usually large cells with voluminous cytoplasm which may contain azurophil granules. The nucleus is often folded and contains 3-5 nucleoli.

It is difficult in some cases to differentiate myeloblasts from lymphoblasts and cytochemistry and immunophenotyping may then be helpful.

Myeloblasts are typically Sudan black and Myeloperoxidase positive and PAS negative. They are often diffusely positive for non-specific esterase (NSE).

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) illustrating the role and limitations of flow cytometry in blast enumeration.

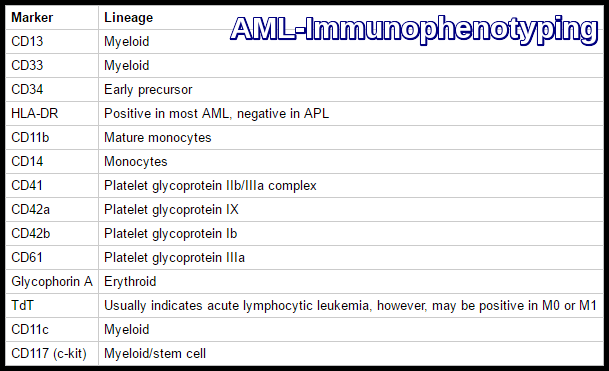

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) immunophenotyping markers used for lineage assignment and subtype classification.

Monoblasts are more strongly positive for NSE.

Classification:

Peripheral blood smear in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), hypogranular variant, showing bilobed promyelocytes with scant cytoplasmic granulation and visible Auer rods (May–Grünwald–Giemsa stain, ×100).

Bone marrow smear in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), hypergranular variant, showing densely granulated promyelocytes, including a cell containing multiple Auer rods (May–Grünwald–Giemsa stain, ×100).

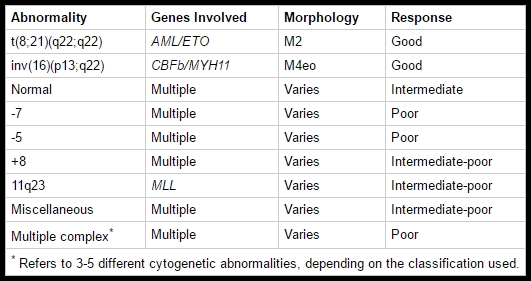

Cytogenetic Analysis:

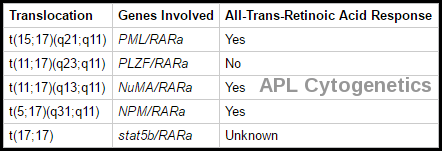

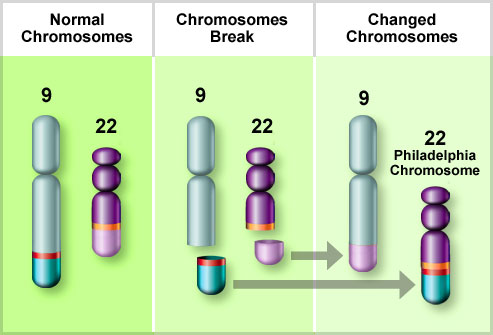

Cytogenetic studies performed on bone marrow provide important prognostic information. They are useful for confirming a diagnosis of APL, which bears the t(15;17) chromosome abnormality (PML/RARa) and is treated differently.

Chromosomal abnormalities are seen in the majority of cases; t(15;17), inv(16) and t(8;21) are good prognostic features whereas trisomy 8, monosomy 7 and monosomy 5 are poor prognosis disease.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies can be used to get a faster overview of cytogenetic abnormalities than traditional cytogenetic studies. FISH does not replace cytogenetics.

Cytogenetic translocations in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and response to all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).

Molecular Marrow Evaluation:

Several molecular abnormalities that are not detected with routine cytogenetics have been shown to have prognostic importance in patients with AML. The bone marrow should be evaluated at least with the commercially available tests. Patients with APL should have their marrow evaluated for the PML/RARa genetic rearrangement. When possible, the bone marrow should be evaluated for Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and nucleophosmin (NPM1) mutations.

FLT3 is the most commonly mutated gene in persons with AML and is constitutively activated in one-third of AML cases. Internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in the juxtamembrane domain of FLT3 exist in 25% of AML cases. In other cases, mutations exist in the activation loop of FLT3. Most studies demonstrate that patients with FLT3-ITD mutations tend to have a particularly unfavorable prognosis, with an increased risk of relapse and shorter overall survival (OS) compared with patients without the mutation . Analysis of FLT3 is commercially available.

Mutations in NPM1 are associated with increased response to chemotherapy in patients with a normal karyotype.

Treatment of AML:

AML poses a significant clinical challenge due to its heterogeneity and resistance to conventional therapies. Recent research has focused on unravelling the intricate genetic and molecular landscape of AML, paving the way for more precise and effective treatment options.

Supportive treatment:

Includes transfusion for anemia, treatment of infections, platelets for bleeding, and social and psychological support. Patients should receive leucodepleted, irradiated blood products to reduce the risk of transfusion-associated graft versus host disease, cytomegalovirus (CMV) transmission, and febrile transfusion reactions. Patients usually receive packed red cells when the hemoglobin level falls below 8 g/dL, those with significant respiratory and cardiac disease might require transfusion at a higher hemoglobin level. Patients receive platelet transfusions when the platelet count is <10,000/mm3. Patients with active bleeding will be transfused to a platelet count of 50,000/mm3; patients with CNS hemorrhage should be transfused to a platelet count of 100,000/mm3. If disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is present (M3) large numbers of platelets and clotting factor replacement therapy are required.

Induction chemotherapy:

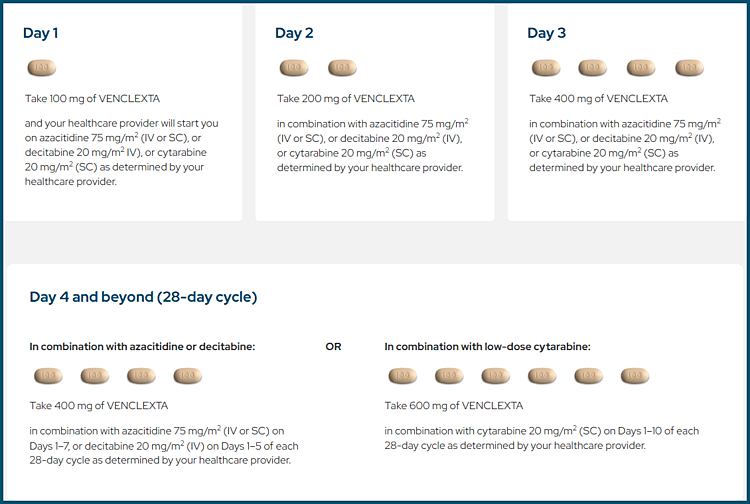

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is primarily a disease of older adults, with a median age of 68 years at diagnosis. Standard curative treatment for AML consists of intensive induction chemotherapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy, allogeneic stem-cell transplantation, or both. However, because of advanced age, coexisting conditions, and a high incidence of unfavourable genomic features, older patients are frequently ineligible for or have a disease that is refractory to standard chemotherapy. Instead, such patients often receive less intensive regimens, including hypomethylating agents (azacitidine or decitabine) and low-dose cytarabine. Among untreated patients with AML who are at least 65 years of age, azacitidine monotherapy has been associated with an incidence of remission of 30% or less and survival of less than one year.

Initial therapy attempts to induce remission and differs most from ALL in that AML responds to fewer drugs. The primary induction regimen includes cytarabine (ara-C) by continuous IV infusion or high doses for 5 to 7 days; daunorubicin or idarubicin is given IV for three days. This is sometimes called a 7 + 3 regimen because it consists of getting cytarabine continuously for 7 days, along with short infusions of an anthracycline on each of the first 3 days.

People with poor heart function might not be able to be treated with anthracyclines so that they may be treated with another chemo drug, such as fludarabine or etoposide.

In some situations, a third drug might be added as well to try to improve the chances of remission:

- For people whose leukemia cells have an FLT3 gene mutation, a targeted therapy drug such as midostaurin (Rydapt) or quizartinib (Vanflyta) might be given along with chemo.

- For people whose leukemia cells have the CD33 protein, the targeted drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) might be added to chemo.

- Adding the chemo drug cladribine might be another option for some people.

Some regimens include 6-thioguanine, etoposide, vincristine, and prednisone, but their contribution is unclear. Treatment usually results in significant myelosuppression, with infection or bleeding. There is significant latency before marrow recovery. During this time, meticulous preventive and supportive care is vital.

In previously untreated patients who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy, overall survival was longer, and the incidence of remission was higher among patients who received Azacitidine plus Venetoclax (Venclexta) than among those who received azacitidine alone. The incidence of febrile neutropenia was higher in the venetoclax–azacitidine group than in the control group.

In rare cases where the leukemia has spread to the brain or spinal cord, chemo may also be given into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Radiation therapy might be used as well.

People typically need to stay in the hospital during induction (and possibly for some time afterwards). Induction destroys most of the normal bone marrow cells as well as the leukemia cells, so most people develop dangerously low blood counts, and may be very ill. Most people need antibiotics and blood product transfusions. Drugs to raise white blood cell counts (growth factors) may also be used. Blood counts tend to stay low for a few weeks.

About a week after chemo is done, the doctor will do a bone marrow biopsy. It should show few bone marrow cells (hypocellular bone marrow) and only a tiny portion of blasts (making up no more than 5% of the bone marrow) for leukemia to be considered in remission. Most people with leukemia go into remission after the first round of chemo. But if the biopsy shows that there are still leukemia cells in the bone marrow, another round of chemo may be given, either with the same drugs or with another regimen. Sometimes, a stem cell transplant is recommended at this point. If it isn’t clear on the bone marrow biopsy whether the leukemia is still there, another bone marrow biopsy may be done again in about a week.

Over the next few weeks, normal bone marrow cells will return and start making new blood cells. The doctor may do other bone marrow biopsies during this time. When the blood cell counts recover, the doctor will again check cells in a bone marrow sample to see if the leukemia is in remission.

Remission induction usually does not destroy all the leukemia cells, and few often remain. Without post-remission therapy (consolidation), the leukemia is likely to return within several months. Induction is considered successful if remission is achieved. Further treatment (called consolidation) is then given to try to destroy any remaining leukemia cells and help prevent a relapse.

Advancements in genomic sequencing technologies have enabled comprehensive molecular profiling of AML patients. Identification of specific mutations, such as FLT3, NPM1, and IDH1/2, has allowed for personalized treatment approaches. Targeting these mutations with specific inhibitors has shown promising results in clinical trials.

Targeted Therapies:

FLT3 Inhibitors: Mutations in FLT3 are prevalent in AML and associated with poor prognosis. Recent trials have demonstrated the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors, such as midostaurin and gilteritinib, either alone or in combination with standard chemotherapy.

IDH Inhibitors: Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations are found in a subset of AML cases. Inhibitors targeting mutant IDH1 (ivosidenib) and IDH2 (enasidenib) have shown efficacy, providing a promising therapeutic option.

Immunotherapy:

Immunotherapeutic strategies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, are being explored in AML. Early clinical trials have shown promising responses, although further research is needed to optimize these approaches.

In August 2017 the US FDA approved CPX-351 (vyxeos), a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin at a fixed 5:1 molar ratio, for the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC) and therapy-related AML (t-AML). This is the first approved treatment specifically for patients with this subgroup of AML. The approval was based on findings from a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III study of CPX-351 Versus 7 + 3 in patients 60-75 years old with newly diagnosed AML-MRC or t-AML. In a study CPX-351 had a higher median OS than 7 + 3 (9.56 vs 5.95 months, HR 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52 to 0.90, p = 0.005).

Vyxeos (CPX-351), a liposomal formulation of daunorubicin and cytarabine, used in high-risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).

Consolidation therapy (post-remission therapy):

Induction is considered successful if remission is achieved. Further treatment (called consolidation) is then given to try to destroy any remaining leukemia cells and help prevent a relapse.

Consolidation for younger people:

For younger people (typically those under 60), the main options for consolidation therapy are:

- High-dose cytarabine (ara-C) (sometimes known as HiDAC)

- Allogeneic (donor) stem cell transplant

- Autologous stem cell transplant

The best option for each person depends on the risk of the leukemia coming back after treatment, as well as other factors. For HiDAC, cytarabine is given at very high doses, typically over 5 days. This is repeated about every 4 weeks, usually for a total of 3 or 4 cycles. Again, each round of treatment is typically given in the hospital because of the risk of serious side effects.

For people who got a targeted drug such as midostaurin (Rydapt) or quizartinib (Vanflyta) along with chemo during induction, this is typically continued during consolidation.

For people who got chemo plus the targeted drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) for their induction therapy, a similar regimen might be used for consolidation.

Another approach after induction therapy is to give very high doses of chemo followed by either an allogeneic (from a donor) or autologous (patient’s own) stem cell transplant. Stem cell transplants have been found to reduce the risk of leukemia coming back more than standard chemo, but they are also more likely to have serious complications, including an increased risk of dying from treatment.

Consolidation for people who are older or have other health problems:

Older people or those in poor health may be unable to tolerate intensive consolidation treatment. Often, giving them more intensive therapy raises the risk of serious side effects (including dying from treatment) without providing much more of a benefit. These people may be treated with:

- Higher-dose cytarabine (usually not quite as high as in younger people).

- Standard-dose cytarabine, possibly along with idarubicin, daunorubicin, or mitoxantrone (For people who got a targeted drug such as midostaurin or quizartinib during induction, this is typically continued during consolidation as well).

- A non-myeloablative stem cell transplant (mini-transplant).

Treating frail or older adults:

Treatment of AML in people under 60 is fairly standard. It involves cycles of intensive chemo, sometimes along with a targeted drug or a stem cell transplant (as discussed above). Many people older than 60 are healthy enough to be treated similarly, although sometimes the chemo may be less intense.

People who are much older or in poor health may be unable to tolerate this intense treatment. In fact, intense chemo could actually shorten their lives. Treatment of these people is often not divided into phases, but it may be given every so often as long as it seems helpful.

Options for people who are older or are in poor health might include:

Low-intensity chemo with a drug such as low-dose cytarabine (LDAC), azacitidine (Vidaza), or decitabine (Dacogen).

Low-intensity chemo plus a targeted drug such as venetoclax (Venclexta) or glasdegib (Daurismo).

A targeted drug, such as:

- Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), if the AML cells have the CD33 protein.

- Ivosidenib (Tibsovo), alone or with the chemo drug azacitidine, if the AML cells have an IDH1 gene mutation.

- Enasidenib (Idhifa), if the AML cells have an IDH2 gene mutation

Some people might decide against chemo and other drugs and instead choose only supportive care. This focuses on treating any symptoms or complications that arise and keeping the person as comfortable as possible.

Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL):

In APL and some other cases of AML, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may be present when leukemia is diagnosed and may worsen as leukemic cell lysis releases procoagulant. APL is a particularly important subtype, representing 10 to 15% of all cases of AML, striking a younger age group (median age 31 years) and particular ethnicity (Hispanics), in which the patient commonly presents with a coagulation disorder. In APL with the translocation t(15;17), all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA/tretinoin) corrects the DIC in 2 to 5 days; combined with daunorubicin or idarubicin, this regimen can induce remission in 80 to 90% of patients and bring about long-term survival in 65 to 70%. Arsenic trioxide (ATO) is also very active in APL.

The most important side effect of ATRA and ATO is known as differentiation syndrome (previously called retinoic acid syndrome). This occurs when the leukemia cells release certain chemicals into the blood. It is most often seen during the first couple of weeks of treatment, and in patients with a high white blood cell count. Symptoms can include fever, breathing problems due to fluid buildup in the lungs and around the heart, low blood pressure, kidney damage, and severe fluid buildup elsewhere in the body. While differentiation syndrome can be serious, it can often be treated by stopping the drugs for a while and giving a steroid such as dexamethasone.

Relapse:

Patients who have not responded to treatment and younger patients who are in remission but who are at high risk of relapse (generally identified by high-risk molecular or chromosomal abnormalities) may be given high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Extramedullary sites are infrequently involved in isolated relapse. When relapse occurs, additional chemotherapy for patients unable to undergo stem cell transplantation is less effective and often poorly tolerated. Another course of chemotherapy is most effective in younger patients and in patients whose initial remission lasted > 1 year.

Prognosis of AML:

Remission induction rates range from 50 to 85%. Long-term disease-free survival occurs in 20 to 40% of patients and increases to 40 to 50% in younger patients treated with intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation.

Prognostic factors help determine treatment protocol and intensity; patients with strongly negative prognostic features are usually given more intense forms of therapy because the potential benefits are thought to justify the increased treatment toxicity. An important prognostic factor is the leukemia cell karyotype. The specific chromosomal rearrangements of the different forms of AML affect the outcome.

Three clinical groups have been identified: favorable, intermediate, and poor. Patients who have the cytogenetic findings of t(8;21), t(15;17), and inv(16) typically have a favorable response to therapy, durable remission, and improved survival. Patients with a normal karyotype have an intermediate prognosis, and patients with a poor prognosis are those with a deletion of chromosome 5 or 7, trisomy 8, or a karyotype with > 3 abnormalities.

Molecular genetic abnormalities are becoming more important in refining prognosis and therapy in AML. Mutations in FLT3 kinase in particular indicate a poorer prognosis and are targets for additional therapy. Other negative factors include increasing age, a preceding myelodysplastic phase, secondary leukemia, high WBC count, and absence of Auer rods. Except in APL, the FAB or WHO classification alone does not predict response.

Travel Insurance:

Travel insurance considerations for patients with cancer, including leukemia and other hematologic malignancies.

Travel insurance is very important for people who have or have had cancer. Getting travel insurance when you have acute leukemia can be difficult.

Insurance companies only make money from people who don’t claim. Because you’ve been ill, they think you’re more likely to claim. For example, you might need to cancel your trip or have medical treatment abroad. This makes you a bigger risk to the company, and they can refuse to give you travel insurance.

When traveling abroad, if you are receiving active treatment for your leukemia especially chemotherapy this may affect your immune system making you more prone to infections. Also, certain vaccinations are not recommended for people traveling with leukemia.

Some high street travel insurance companies will give you medical insurance if you have a doctor’s letter saying you’re fit enough to travel. But many others will insure you only for treatment that isn’t to do with your cancer.

Further information on getting travel insurance if you have leukemia is available from Cancer Research UK.

Questions and Answers:

What is acute myeloid leukemia (AML)?

Acute myeloid leukemia is an aggressive blood cancer caused by uncontrolled proliferation of immature myeloid cells (myeloblasts) in the bone marrow and blood, leading to bone marrow failure and rapid clinical deterioration if untreated.

How is AML diagnosed?

AML is diagnosed when myeloblasts constitute 20% or more of nucleated cells in the bone marrow or peripheral blood, supported by morphology, immunophenotyping, cytogenetics, and molecular testing.

What are the common symptoms of AML?

Symptoms of AML include fatigue and pallor due to anemia, infections due to neutropenia, bleeding or bruising from thrombocytopenia, bone pain, fever, and weight loss.

What do myeloblasts look like on a blood film in AML?

Myeloblasts in AML are large immature cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, fine chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and may contain Auer rods, which confirm myeloid lineage.

What are Auer rods and why are they important in AML?

Auer rods are needle-shaped cytoplasmic inclusions formed from fused primary granules and are diagnostic of myeloid differentiation, most commonly seen in acute myeloid leukemia, particularly acute promyelocytic leukemia.

What is acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)?

APL is a distinct subtype of AML characterized by abnormal promyelocytes and the PML-RARA fusion gene, associated with a high risk of coagulopathy but excellent prognosis with targeted therapy.

What is the difference between hypergranular and hypogranular APL?

Hypergranular APL shows heavily granulated promyelocytes, while hypogranular APL features bilobed nuclei with scant granules and may mimic other AML subtypes, making early recognition critical.

Why is early treatment critical in APL?

APL carries a high risk of life-threatening disseminated intravascular coagulation, and immediate initiation of all-trans retinoic acid is essential even before genetic confirmation.

What is the role of bone marrow biopsy in AML?

Bone marrow biopsy confirms the diagnosis of AML, assesses marrow cellularity and architecture, evaluates fibrosis, and provides material for cytogenetic and molecular studies.

How is flow cytometry used in AML diagnosis?

Flow cytometry confirms myeloid lineage, identifies monocytic or aberrant marker expression, and helps distinguish AML from acute lymphoblastic leukemia, although morphology remains the gold standard for blast enumeration.

Which immunophenotypic markers are typical of AML?

AML commonly expresses myeloid markers such as CD13, CD33, CD117, and CD34, with variable expression of HLA-DR, which is typically negative in acute promyelocytic leukemia.

What is the FAB classification of AML?

The FAB classification categorizes AML into subtypes M0–M7 based on morphology and cytochemistry, and although superseded by WHO and ICC systems, it remains useful for morphological understanding.

How do cytogenetic abnormalities affect AML prognosis?

Cytogenetic abnormalities are major prognostic factors in AML, with favorable outcomes seen in t(8;21) and inv(16), and poor prognosis associated with complex karyotypes and chromosome 5 or 7 abnormalities.

What is the significance of the t(15;17) translocation in AML?

The t(15;17) translocation produces the PML-RARA fusion gene, defining APL and predicting sensitivity to all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide therapy.

What is venetoclax and how is it used in AML?

Venetoclax is a BCL-2 inhibitor used in combination with hypomethylating agents or low-dose cytarabine in older or unfit AML patients, requiring dose ramp-up to reduce tumour lysis risk.

What is Vyxeos (CPX-351) and who should receive it?

Vyxeos is a liposomal formulation of daunorubicin and cytarabine indicated for therapy-related AML and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes, offering improved survival compared with standard chemotherapy.

What is Onureg and when is it used in AML?

Onureg is an oral azacitidine formulation used as maintenance therapy in adult AML patients in first remission who are not candidates for immediate stem cell transplantation.

Can AML cause gum swelling or gingival infiltration?

Yes, gingival infiltration is a recognized extramedullary manifestation of AML, particularly in monocytic subtypes, and may be an early presenting sign.

Is AML curable?

AML can be cured in a proportion of patients, particularly those with favorable genetic risk, with outcomes dependent on age, cytogenetics, molecular profile, response to therapy, and access to stem cell transplantation.

References:

Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100(7):2292–2302.

Smith MT, Skibola CF, Allan JM, Morgan GJ. Causal models of leukaemia and lymphoma. IARC Scientific Publications. 2004:373–392.

Ghiaur G, Wroblewski M, Loges S. Acute myelogenous leukemia and its microenvironment: a molecular conversation. Seminars in Hematology. 2015;52(3):200–206.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Version 1.2015.

Haferlach C, Alpermann T, Schnittger S, Kern W, Chromik J, Schmid C, et al. Prognostic value of monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(9):2122–2125.

DiNardo CD, Cortes JE. New treatment strategies for acute myelogenous leukemia. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2015;16(1):95–106.

Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, et al. Diagnostic cytogenetics and outcome in AML: MRC AML 10 trial. Blood. 1998;92(7):2322–2333.

Seiter K, Besa EC. Acute Myelogenous Leukemia: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology. Medscape Reference.

Rytting ME. Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML). Merck Manual Professional Edition.

Fenaux P, Chastang C, Chevret S, Sanz M, Dombret H, et al. ATRA and chemotherapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(4):1192–1200.

Giles F, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Outcomes after second salvage therapy in AML. Cancer. 2005;104(3):547–554.

Bain BJ, Béné MC. Morphological and immunophenotypic clues to WHO categories of AML. Acta Haematologica. 2019;141(4):232–244.

Alfayez M, Kantarjian H, Kadia T, Ravandi F, Daver N. CPX-351 (Vyxeos) in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2020;61(2):288–297.

Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for FLT3-mutated AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:454–464.

Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib vs chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory FLT3-mutated AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381:1728–1740.

DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, et al. Ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378:2386–2398.

Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, et al. Enasidenib in IDH2-mutated AML. Blood. 2017;130(6):722–731.

Daver N, Garcia-Manero G, Basu S, et al. Azacitidine plus nivolumab in AML. Cancer Discovery. 2019;9(3):370–383.

Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:2209–2221.

DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Wei AH, Konopleva M, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in untreated AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020.

Cui Y, Mi R, Chen L, Wang L, Li D, Wei X. Venetoclax plus azacitidine in acute undifferentiated leukemia. Hematology. 2024;29(1).

American Cancer Society. Typical Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Except APL).

Cancer Research UK. Getting travel insurance after cancer.

Morphology Cases. Blood-Academy.com.

VENCLEXTA®. Venetoclax dosing schedule for AML.

Keywords:

acute myeloid leukemia, acute myeloid leukaemia, AML, AML leukemia, acute leukemia myeloid, AML blood cancer, acute myeloid leukemia symptoms, AML signs and symptoms, acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis, AML diagnostic criteria, bone marrow biopsy AML, myeloblasts AML, Auer rods AML, acute promyelocytic leukemia, APL leukemia, hypogranular APL, hypergranular APL, PML RARA translocation, AML immunophenotyping, AML flow cytometry, AML cytogenetics, AML molecular mutations, FLT3 mutation AML, NPM1 mutation AML, IDH1 AML, IDH2 AML, AML prognosis, AML prognosis by age, AML prognosis elderly, AML survival rate, AML treatment, AML treatment guidelines, AML chemotherapy, AML induction therapy, AML consolidation therapy, AML stem cell transplant, AML targeted therapy, venetoclax AML, azacitidine AML, venetoclax azacitidine AML, Vyxeos CPX-351 AML, Onureg oral azacitidine AML, AML maintenance therapy, AML relapse treatment, therapy-related AML, AML with myelodysplasia-related changes, AML ICD-10, AML UK prognosis, leukemia hematology, blood cancer leukemia, Ask Hematologist, Dr Moustafa Abdou

thanks Dr. for all these information

I have not been diagnosed with Leukemia, however after a lot of medical radiation am worried that may cause leukemia, especially as my father had it. due to having high ferritin reading ( no obvious cause and normal iron ) I have regular blood checks.

On March 1st my blood film showed ‘Neutrophils showed left shift, WBC count was 5.7 and Neutrophils 3.57

On March 15th blood film reported ‘slight neutrophil show toxic granulation, WBC was 6.42 and Neutrophils 3.67

On in April blood test reported no abnormal issues WBC was 6.7, Neutrophils 4.46

On June 23rd, CBC reported normal but comment neutrophils show left shift WBC was 5.2 and Neutrophil 2.77

On July 1st, CBC again reported as normal no left shift detected, WBC 5.8, Neutrophils 2.98

I fully understand that left shift would be reaction to infection ( I had neither that I knew of at time of left shift reports ) but surely if I had an infection both my WBC and Neuts would also show an increase, clearly in the last two test if anything they are showing a reduction.

Having read your acute leukaemia report I am concerned I may have some kind of pre leukemic condition as you mentioned that could reduce WBC and Neuts.

Any advice/comments welcome.

Alan

Hi Alan,

Thanks for your comment.

The left shift means the appearance of some less mature forms on the blood film like band neutrophils and metamyelocytes. These are commonly seen in response to infection or inflammation. Raised ferritin could also be reactive to an underlying infection, inflammation, liver disease, alcohol excess not only in malignancy. I would suggest avoiding doing frequent blood tests because it would provoke unnecessary anxiety for you. You haven’t mentioned the irradiation dose you have previously received and for which indication? Generally speaking, if leukaemia will happen no one can prevent it!

I would suggest repeating your CBC only if you have symptoms, otherwise just once a year.

BW,