Spherocytosis

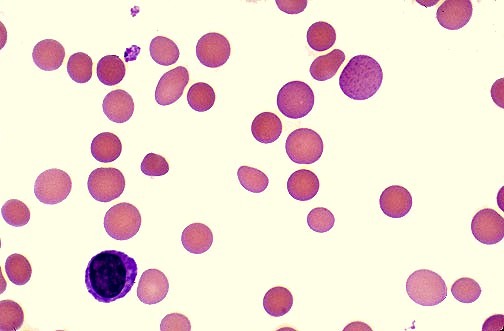

Peripheral blood smear in hereditary spherocytosis demonstrating multiple spherocytes with dense staining and loss of central pallor, a hallmark feature of red blood cell membrane disorders.

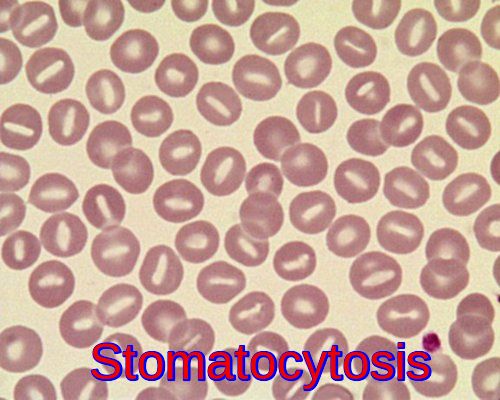

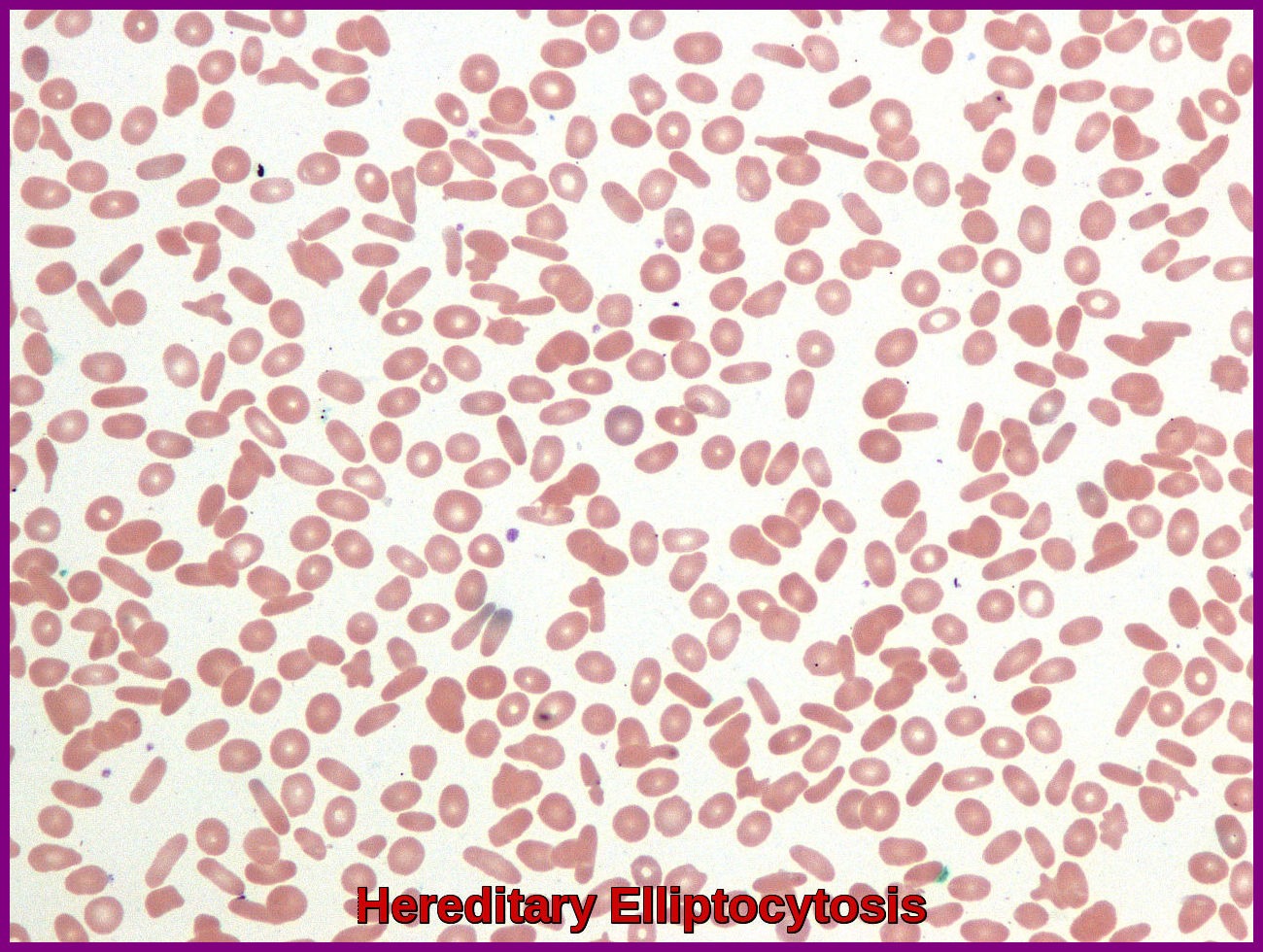

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is the most common inherited red blood cell membrane disorder, typically transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is characterized by structurally abnormal red blood cells that become spherical (spherocytes), rigid, and osmotically fragile. On peripheral blood smear, these cells appear smaller, dense, and deeply stained with loss of central pallor. While spherocytes may be seen to varying degrees in many hemolytic anemias, only hereditary spherocytosis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia are defined by a predominance of spherocytes; however, the term spherocytosis most commonly refers to hereditary spherocytosis itself.

Hereditary spherocytosis results from defects in key structural proteins of the red blood cell membrane, particularly spectrin, ankyrin, band 3 protein, and protein 4.2. These defects impair membrane stability, reduce cellular deformability, and promote progressive membrane loss, leading to the formation of rigid spherical erythrocytes. As a consequence, affected red cells are prematurely trapped and destroyed within the spleen, producing chronic extravascular hemolysis. The clinical presentation of spherocytosis varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic disease to severe lifelong hemolytic anemia with jaundice, splenomegaly, and gallstone formation.

Under normal physiological conditions, a red blood cell survives in circulation for approximately 120 days. In contrast, in hereditary spherocytosis, red cell lifespan may be dramatically shortened to as little as 10–30 days, depending on disease severity and splenic activity.

Peripheral blood smear in hereditary spherocytosis demonstrating widespread spherocytes with dense staining and absent central pallor, reflecting red blood cell membrane protein defects and extravascular hemolysis.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis is based on an integrated assessment of clinical features, laboratory findings, and specialized confirmatory testing. Peripheral blood smear examination remains a cornerstone of diagnosis and typically demonstrates characteristic spherocytes—small, dense red blood cells with loss of central pallor.

Peripheral blood smear in hereditary spherocytosis demonstrating numerous spherocytes with dense staining and absence of central pallor, associated polychromasia from reticulocytosis, and a background of residual biconcave erythrocytes, reflecting chronic extravascular hemolysis.

Laboratory evaluation usually reveals evidence of chronic hemolysis, including anemia of variable severity, reticulocytosis, indirect hyperbilirubinemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and reduced or absent haptoglobin.

Traditional osmotic fragility testing demonstrates increased red blood cell susceptibility to hypotonic lysis; however, this test may be normal in mild disease. More sensitive and specific modern tests include the eosin-5-maleimide (EMA) binding test by flow cytometry, which is now considered the preferred screening test for hereditary spherocytosis due to its high sensitivity and specificity. Molecular genetic testing can be used to identify pathogenic mutations in red blood cell membrane protein genes such as spectrin, ankyrin, band 3, and protein 4.2, particularly in atypical cases or for family counseling.

Splenomegaly is a frequent clinical finding and is usually detectable on physical examination. Anemia is typically mild to moderate but may worsen significantly during aplastic crises, most commonly triggered by parvovirus B19 infection, or during hemolytic crises associated with increased splenic sequestration. Due to chronic erythropoietic stress, folate deficiency may develop and should be actively screened for and prevented with supplementation.

Massive splenomegaly in hereditary spherocytosis demonstrated at splenectomy, a definitive therapeutic option in severe disease to reduce extravascular hemolysis, transfusion requirements, and anemia severity.

Jaundice is often mild or intermittent but may become more pronounced during hemolytic episodes; in neonates, severe hyperbilirubinemia may rarely lead to kernicterus. Pigmented gallstones are a common long-term complication and occur in approximately half of untreated patients due to chronic bilirubin overproduction.

An important metabolic finding in hereditary spherocytosis is abnormally low hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, reflecting the shortened red blood cell lifespan. This results in reduced exposure time for non-enzymatic glycation of hemoglobin and may lead to falsely reassuring HbA1c values despite elevated mean blood glucose levels, which is clinically important when assessing glycemic control in diabetic patients with hereditary spherocytosis.

Management:

The management of hereditary spherocytosis is individualized according to disease severity, age, symptom burden, and the presence of complications. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce hemolysis, prevent long-term complications, and optimize quality of life. Many patients with mild disease require only observation and supportive care, while those with moderate to severe disease may need definitive intervention.

Folate supplementation is routinely recommended for most patients with hereditary spherocytosis due to chronic hemolysis and sustained marrow hyperactivity with increased erythropoietic demand. This helps prevent secondary folate deficiency and supports effective red blood cell production.

Splenectomy remains the most effective disease-modifying treatment for moderate to severe hereditary spherocytosis. Removal of the spleen markedly reduces red blood cell destruction, corrects anemia, and lowers bilirubin levels. When indicated, splenectomy is preferably deferred until after early childhood (usually after 5–6 years of age) to reduce the lifelong risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI). The decision to proceed with splenectomy must balance the expected hematologic benefit against the long-term infectious and thrombotic risks. Partial splenectomy may be considered in selected pediatric cases to preserve some immune function.

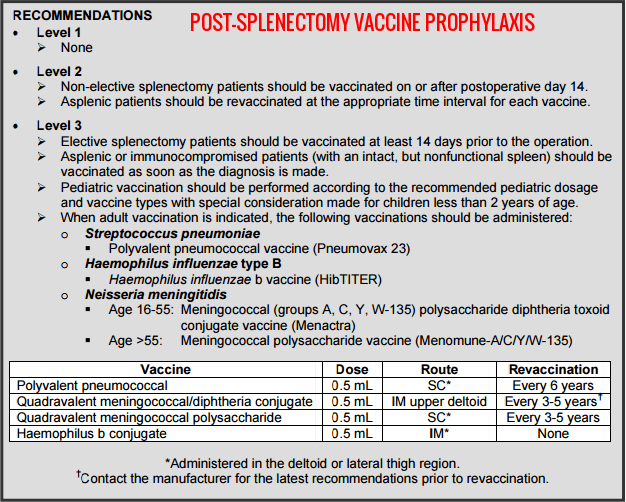

Vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis are mandatory in splenectomized patients. Immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Neisseria meningitidis should be completed preoperatively where possible. Long-term penicillin prophylaxis is recommended, particularly in children, and patients must receive urgent medical assessment for any febrile illness due to the risk of OPSI.

Red blood cell transfusions are reserved for patients with severe anemia, most commonly during early childhood, aplastic crises (e.g., parvovirus B19 infection), pregnancy, or major intercurrent illness. In patients requiring repeated transfusions, monitoring for transfusional iron overload is essential, and iron chelation therapy should be initiated when indicated.

It is important to recognize that while spherocytes may also be observed in immune-mediated hemolytic anemias, particularly warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia, the management strategy in hereditary spherocytosis is fundamentally different and centered on splenic modulation rather than immunosuppression.

With appropriate monitoring and timely intervention, the long-term prognosis of hereditary spherocytosis is generally excellent, and most patients achieve normal life expectancy with good functional outcomes.

Post-splenectomy vaccine prophylaxis recommendations showing the required immunization schedule against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae type B to reduce the risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection in hereditary spherocytosis and other asplenic states.

Summary:

Hereditary spherocytosis is the most common inherited red blood cell membrane disorder, characterized by the formation of rigid spherical erythrocytes that are prematurely destroyed in the spleen, leading to chronic hemolytic anemia. Caused by defects in key membrane proteins such as spectrin, ankyrin, band 3, and protein 4.2, the disease presents with variable severity ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe anemia with jaundice, splenomegaly, gallstones, and hemolytic crises. Diagnosis relies on peripheral blood smear findings, hemolysis markers, osmotic fragility or EMA binding testing, and molecular confirmation when required. Management is tailored to disease severity and includes folate supplementation, blood transfusions during crises, vaccination and prophylactic antibiotics in splenectomized patients, and splenectomy for moderate to severe disease to reduce hemolysis and improve anemia. With appropriate monitoring, preventive care, and timely intervention, the long-term prognosis of hereditary spherocytosis is excellent, and most patients enjoy a normal life expectancy and quality of life.

Questions and Answers:

What is hereditary spherocytosis?

Hereditary spherocytosis is an inherited red blood cell membrane disorder in which erythrocytes become spherical, rigid, and prone to premature destruction in the spleen, causing chronic hemolytic anemia.

What causes hereditary spherocytosis?

Hereditary spherocytosis is caused by genetic defects in red blood cell membrane proteins such as spectrin, ankyrin, band 3, and protein 4.2, leading to membrane instability and spheroidal red cells.

What are the main symptoms of hereditary spherocytosis?

Common symptoms include anemia, jaundice, splenomegaly, fatigue, gallstones, and intermittent hemolytic or aplastic crises, with severity varying from mild to life-threatening disease.

How is hereditary spherocytosis diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on peripheral blood smear showing spherocytes, laboratory evidence of hemolysis, EMA binding test or osmotic fragility testing, and genetic testing in selected cases.

How is hereditary spherocytosis treated?

Treatment depends on severity and includes folate supplementation, blood transfusions during crises, iron chelation if transfusion overload occurs, and splenectomy in moderate to severe disease.

Why is splenectomy performed in hereditary spherocytosis?

Splenectomy reduces red blood cell destruction, corrects anemia, lowers bilirubin levels, and improves quality of life in patients with moderate to severe hereditary spherocytosis.

What vaccines are required after splenectomy in hereditary spherocytosis?

Post-splenectomy patients must receive vaccines against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Neisseria meningitidis, along with long-term antibiotic prophylaxis.

Is the prognosis good for hereditary spherocytosis?

Yes, with appropriate monitoring, vaccination, and timely splenectomy when indicated, most patients with hereditary spherocytosis have an excellent long-term prognosis and normal life expectancy.

References:

Bolton-Maggs P.H., Langer J.C., Iolascon A., et al.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary spherocytosis – 2011 update. British Journal of Haematology. 2012;156:37–49.

Perrotta S., Gallagher P.G., Mohandas N.

Hereditary spherocytosis. The Lancet. 2008;372:1411–1426.

Department of Surgical Education, Orlando Regional Medical Center.

Post-splenectomy vaccine prophylaxis guidelines.

Kutter D., Thoma J.

Hereditary spherocytosis and other hemolytic anomalies distort diabetic control by glycated hemoglobin. Clinical Laboratory. 2006;52(9–10):477–481.

British Committee for Standards in Haematology.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. BMJ. 1996;312:430–434.

Health Jade Editorial Team.

Spherocytosis. Available at: https://healthjade.com/spherocytosis/

Hillman R.S., Ault K.A., Rinder H.M.

Hematology in Clinical Practice: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005:146–150. ISBN: 978-007144035-6.

Shah S., Vega R.

Hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatrics in Review. 2004;25(5):168–172. doi:10.1542/pir.25-5-168.

Keywords:

spherocytosis, hereditary spherocytosis, spherocytes blood smear, hereditary spherocytosis diagnosis, hereditary spherocytosis treatment, splenectomy in hereditary spherocytosis, post splenectomy vaccination, hemolytic anemia, red blood cell membrane disorder, spectrin ankyrin band 3 mutation, eosin-5-maleimide EMA test, osmotic fragility test, splenomegaly in hereditary spherocytosis, pigmented gallstones hemolysis, aplastic crisis parvovirus B19, autoimmune hemolytic anemia vs hereditary spherocytosis, spherocytes peripheral smear, pediatric hereditary spherocytosis, HbA1c low hemolysis, extravascular hemolysis spleen, penicillin prophylaxis post splenectomy

Hi, please could you assist me with info, my son hase spherocytosis and my consern is nou that the schools are opening, can i take the chance to send him in this covid 19 epidemic. Please help me with advice…

Hi Danielle,

Thank you for your comment.

If he is not splenectomised, he doesn’t meet the high risk criteria for contracting coronavirus (COVID-19) and he doesn’t need shielding unless he has another medical condition or on medications which could compromise his immune system.

BW,

My son has mild HS and is an elite distance runner. When he gets ill with something like a sinus infection or strep throat, it can derail his entire season. He’ll get over the illness, but his body is evidently still struggling because his heart rate is crazy high when he runs. Is there anything to be done to help him? He has one year of college eligibility left, and I’d love for him to be as healthy as possible.

Hi Marisa,

Thank you for your message and for sharing your concerns regarding your son’s experience with hereditary spherocytosis (HS) and its impact on his athletic performance.

To better assess the degree of hemolysis during these episodes, it would be helpful to review his hemolysis markers, including hemoglobin, MCV, conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, reticulocyte count, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and haptoglobin, if available. These results can offer insight into how significantly his red cells are being affected during or after infections. Could you also clarify whether he has had a splenectomy, or if there is any imaging or clinical assessment indicating splenomegaly? The presence or absence of the spleen can greatly influence the degree of hemolysis and clinical management. It’s also important to keep in mind that infections, dehydration, and hypoxia—all of which can occur with intense athletic activity or illness—can exacerbate hemolysis in HS. Ensuring optimal hydration, avoiding overtraining during illness, and closely monitoring during recovery are essential.

Once these parameters are reviewed, a hematologist may consider optimizing his management further, including discussions around folic acid supplementation, transfusion thresholds, or even splenectomy if not yet performed and clinically appropriate.

BW,

Dr M Abdou