Aplastic Anemia

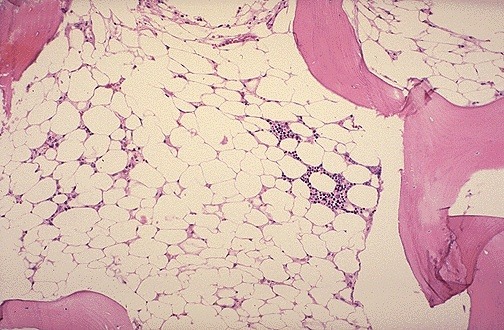

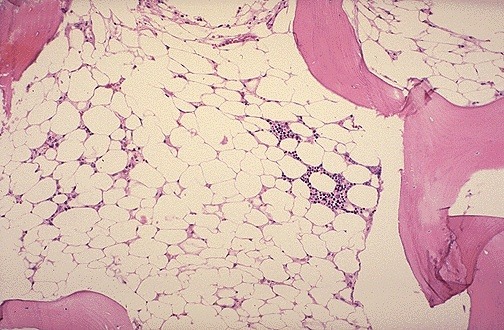

Hypocellular bone marrow with extensive fatty replacement, a classic histologic feature of aplastic anemia.

Aplastic anemia is a rare and serious bone marrow failure disorder in which hematopoietic stem cells become damaged, leading to markedly reduced blood cell production. As a result, patients develop pancytopenia, characterized by anemia (low red blood cells), leukopenia (low white blood cells), and thrombocytopenia (low platelets). The term aplastic refers to the marrow’s inability to generate mature, functional blood cells, resulting in progressive fatigue, infections, and bleeding tendencies.

Most cases of aplastic anemia are acquired, often triggered by autoimmune destruction of hematopoietic stem cells, exposure to medications, toxins, or viral infections. Inherited forms such as Fanconi anemia and Dyskeratosis congenita should also be considered, especially in younger patients. Clinically, the disorder presents with symptoms related to cytopenias, including fatigue from anemia, recurrent infections due to neutropenia, and mucocutaneous bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Early recognition and accurate diagnosis are essential, as timely intervention can significantly improve survival outcomes.

Aetiology:

Congenital:

The commonest of these disorders is Fanconi’s anemia. This is an autosomal recessive disease usually presenting at 4-7 years. Bony and renal abnormalities are common. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually high, the bone marrow appears megaloblastic and HbF is often high.

Characteristic congenital thumb abnormalities seen in Fanconi anemia, a hereditary disorder associated with aplastic anemia.

Acquired:

Acute:

Usually due to infections e.g. parvovirus B19 and acute viral hepatitis infection but can be caused by any of the acquired causes.

Chronic:

- Idiopathic (about half the cases).

- Drugs (e.g. chloramphenicol, carbamazepine, felbamate, phenytoin, quinine, and phenylbutazone), Chemicals (e.g. benzene), irradiation and chemotherapy.

- Infections especially viral hepatitis. Also, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, and HIV.

- An autoimmune disorder in which white blood cells attack the bone marrow.

- Associated with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

- Could rarely associate pregnancy. Sometimes, this type of aplastic anemia improves on its own after the woman gives birth.

Clinical features:

The clinical presentation of aplastic anemia reflects the progressive failure of bone marrow hematopoiesis. The onset is typically insidious, and early symptoms often relate to anemia or thrombocytopenia, although some patients present with neutropenic fever or recurrent infections. The severity of symptoms correlates with the degree of pancytopenia.

Common signs and symptoms include:

- Pallor and reduced exercise tolerance due to anemia

- Headache, palpitations, and exertional dyspnea, reflecting decreased oxygen-carrying capacity

- Fatigue and generalized weakness, often profound in severe cases

- Peripheral edema, occasionally seen in advanced anemia or associated comorbidities

- Mucocutaneous bleeding such as gingival bleeding, epistaxis, easy bruising, and petechial rash secondary to thrombocytopenia

- Recurrent or severe infections due to neutropenia, sometimes presenting with fever at initial diagnosis

- Oropharyngeal ulcerations, particularly in patients with marked neutropenia

- Jaundice and features of acute hepatitis in a subset of patients with hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia

Creamy white plaques of oral candidiasis, an opportunistic fungal infection frequently seen in immunocompromised patients with aplastic anemia.

This constellation of symptoms strongly reflects pancytopenia, a hallmark of aplastic anemia, and should prompt urgent evaluation with a complete blood count and bone marrow examination.

Investigations:

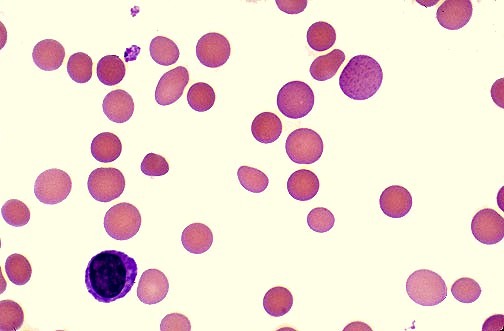

- Anemia (normocytic or mildly macrocytic).

- Absolute reticulocytopenia.

- Absolute granulocytopenia.

- Monocytopenia is usual.

- Thrombocytopenia.

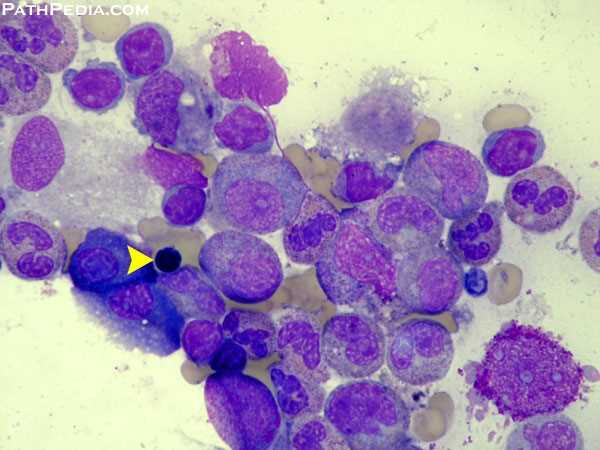

- Bone marrow shows abundant fat spaces and few hematopoietic cells.

Hypocellular bone marrow with prominent fat spaces on H&E staining, a classic histopathologic feature of aplastic anemia.

The condition needs to be differentiated from pure red cell aplasia. In aplastic anemia, the patient has pancytopenia (i.e., anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia). In contrast, pure red cell aplasia is characterized by a reduction in red cells only. The diagnosis can only be confirmed on bone marrow examination. Before this procedure is undertaken, a patient will generally have had other blood tests to find diagnostic clues, including an FBC, U&Es, liver enzymes, thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 and folate levels.

The following tests aid in determining the differential diagnosis of aplastic anemia:

- Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy: to rule out other causes of pancytopenia (i.e. neoplastic infiltration or significant myelofibrosis).

- History of iatrogenic exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy: can cause transient bone marrow suppression.

- X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, or ultrasound imaging tests: enlarged lymph nodes (a sign of lymphoma), kidneys and bones in arms and hands (abnormal in Fanconi anemia).

- Chest X-ray: infections.

- Liver tests: liver diseases.

- Viral studies: viral infections.

- Vitamin B12 and folate levels: vitamin deficiency.

- Blood tests e.g. flow cytometry for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

- Test for antibodies: immune competency.

Treatment:

Supportive care:

- Infection is the most likely cause of death in aplastic anemia and must be treated early and aggressively. Multiple swabs and cultures should be sent before starting broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antifungal agents should be considered if the infection is not controlled with antibiotics alone e.g. Fluconazole, Voriconazole, Caspofungin. Prophylactic antiseptic mouthwash e.g. Corsodyl or Difflam mouth rinse and Mycostatin (Nystatin) mouth drops are usually prescribed.

- Red cell and platelet support must be given when required.

Active treatment:

- Treating immune-mediated aplastic anemia involves suppression of the immune system, an effect achieved by daily medicine intake, or, in more severe cases, a bone marrow transplant, a potential cure. The transplanted bone marrow replaces the failing bone marrow cells with new ones from a matching donor. The multipotent stem cells in the bone marrow reconstitute all three blood cell lines, giving the patient a new immune system, red blood cells, and platelets. However, besides the risk of graft failure, there is also a risk that the newly created white blood cells may attack the rest of the body (“graft-versus-host disease”). In young patients with an HLA-matched sibling donor, bone marrow transplant can be considered as a first-line treatment, patients lacking a matched sibling donor typically pursue immunosuppression as a first-line treatment, and matched unrelated donor transplants are considered second-line therapy.

- Medical therapy of aplastic anemia often includes a course of anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and several months of treatment with cyclosporin to modulate the immune system. Chemotherapy with agents such as cyclophosphamide may also be effective but has more toxicity than ATG. Antibody therapy, such as ATG, targets T-cells, which is believed to attack the bone marrow. Corticosteroids are generally ineffective though they are used to ameliorate serum sickness caused by ATG. Normally, success is judged by bone marrow biopsy 6 months after initial treatment with ATG.

- One prospective study involving cyclophosphamide was terminated early due to a high incidence of mortality, due to severe infections as a result of prolonged neutropenia.

Follow-up:

- Regular full blood counts are required on a regular basis to determine whether the patient is still in a state of remission.

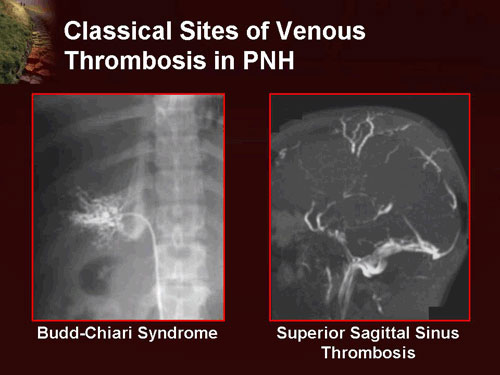

- Many patients with aplastic anemia also have clones of cells characteristic of the rare disease paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH, anemia with thrombopenia and/or thrombosis), sometimes referred to as AA/PNH. Occasionally PNH dominates over time, with the major manifestation intravascular hemolysis. The overlap of AA and PNH has been speculated to be an escape mechanism by the bone marrow against destruction by the immune system. Flow cytometry testing is performed regularly in people with previous aplastic anemia to monitor for the development of PNH. Absence or reduced expression of both CD59 and CD55 on RBCs is diagnostic of PNH.

Prognosis:

- Untreated, severe aplastic anemia has a high risk of death. Treatment, by drugs or stem cell transplant, has a five-year survival rate of about 70%, with younger age associated with higher survival.

- Survival rates for stem cell transplant vary depending on age and availability of a well-matched donor. Five-year survival rates for patients who receive transplants have been shown to be 82% for patients underneath age 20, 72% for those 20–40 years old, and closer to 50% for patients over age 40. Success rates are better for patients who have donors that are matched siblings and worse for patients who receive their marrow from unrelated donors.

- Older people (who are generally too frail to undergo bone marrow transplants), and people who are unable to find a good bone marrow match, undergoing immune suppression have five-year survival rates of up to 75%.

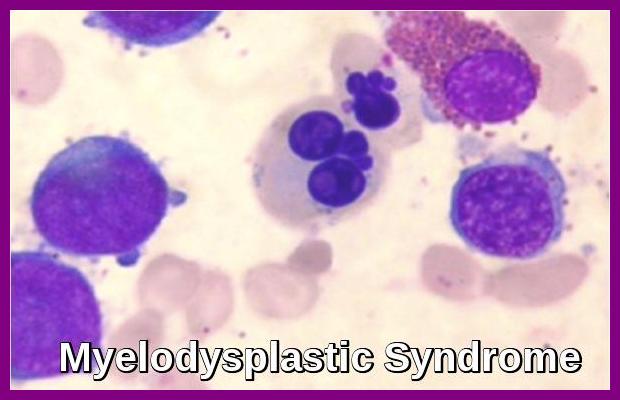

- Relapses are common. Relapse following ATG/Cyclosporin use can sometimes be treated with a repeated course of therapy. In addition, 10-15% of severe aplastic anemia cases evolve into MDS and leukemia. According to a study, for children who underwent immunosuppressive therapy, about 15.9% of children who responded to immunosuppressive therapy encountered relapse.

- The milder disease can resolve with supportive care and stimulating the bone marrow with hematopoietic growth factors such as G-CSF e.g. Filgrastim (Neupogen) or Lenograstim (Granocyte) which may increase the neutrophil count.

Summary:

Aplastic anemia is a serious bone marrow failure disorder characterized by markedly reduced production of red cells, white cells, and platelets, leading to pancytopenia. The condition may be idiopathic or triggered by drugs, toxins, viral infections, autoimmune destruction, pregnancy, or inherited marrow failure syndromes such as Fanconi anemia. Patients commonly present with fatigue, pallor, recurrent infections, mucocutaneous bleeding, and profound reticulocytopenia. Diagnosis is confirmed by blood counts showing pancytopenia and bone marrow biopsy revealing hypocellularity with fatty replacement. Key differential diagnoses include pure red cell aplasia, myelodysplastic syndrome, PNH, and infiltrative marrow disorders. Management involves supportive care, infection prophylaxis, transfusions, immunosuppressive therapy (ATG + cyclosporine), and allogeneic stem cell transplantation, particularly for younger patients with suitable donors. Long-term follow-up is essential due to risks of relapse, clonal evolution (PNH, MDS, AML), and treatment-related complications.

Questions and Answers:

What is aplastic anemia?

Aplastic anemia is a bone marrow failure disorder where the marrow cannot produce enough red cells, white cells, and platelets, resulting in pancytopenia and increased susceptibility to infections, bleeding, and severe anemia.

What causes aplastic anemia?

Causes include idiopathic immune-mediated marrow destruction, drugs such as chloramphenicol and carbamazepine, chemical exposures like benzene, viral infections (hepatitis, EBV, CMV, parvovirus B19, HIV), radiation, pregnancy, and inherited disorders such as Fanconi anemia.

What are the symptoms of aplastic anemia?

Typical symptoms include fatigue, pallor, shortness of breath, recurrent infections due to neutropenia, and mucocutaneous bleeding such as petechiae, epistaxis, or gum bleeding from thrombocytopenia.

How is aplastic anemia diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on CBC showing pancytopenia with low reticulocyte count and bone marrow biopsy demonstrating hypocellularity and fatty replacement. Additional tests help exclude PNH, MDS, viral infections, and other marrow failure causes.

What is the difference between aplastic anemia and pure red cell aplasia?

Aplastic anemia involves failure of all hematopoietic lineages, causing pancytopenia. Pure red cell aplasia affects only erythroid precursors, leading to isolated severe anemia with normal white cells and platelets.

How is aplastic anemia treated?

Treatment includes supportive care, transfusions, antibiotics, immunosuppressive therapy (ATG + cyclosporine), growth factors such as G-CSF in selected cases, and allogeneic stem cell transplant for eligible patients.

Who is a candidate for stem cell transplantation?

Younger patients with severe or very severe aplastic anemia who have a matched sibling donor or a well-matched unrelated donor benefit most from early allogeneic transplant, which offers the highest long-term cure rates.

What is the prognosis for aplastic anemia?

With modern therapies, survival has significantly improved. Patients receiving successful stem cell transplantation or immunosuppression often experience durable recovery, though long-term monitoring is required for relapse and clonal evolution.

Can aplastic anemia evolve into other blood disorders?

Yes. A proportion of patients may evolve into PNH, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute leukemia over time, particularly after prolonged marrow stress or incomplete recovery.

References:

Brodsky RA, Jones RJ. Aplastic anaemia. Lancet. 2005;365:1647–1656.

Young NS. Acquired aplastic anemia. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:534–546.

Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:187–207.

Bacigalupo A, Hows J, Gluckman E, et al. Bone marrow transplantation versus immunosuppression for severe aplastic anaemia: Report of the EBMT SAA Working Party. Br J Haematol. 1988;70:177–182.

Tischkowitz MD, Hodgson SV. Fanconi anaemia. J Med Genet. 2003;40:1–10.

Gonzalez-Casas R, Garcia-Buey L, Jones EA, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Otero R. Hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia: Systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(5):436–443.

Townsend W, Pagliuca A. Aplastic anaemia: Diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2021;373:n1544.

Young NS, Calado RT, Scheinberg P. Aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:933–947.

Scheinberg P, Young NS. How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2012;120(6):1185–1196.

Dufour C, Schlienger G, Pillon M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia: European guidelines. Haematologica. 2022;107(9):2001–2017.

Killick SB, Cavenagh J, Ouwehand W, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia. Blood. 2016;128(22):2326–2335.

NIH/MedlinePlus. Aplastic Anemia – Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment. National Institutes of Health.

American Society of Hematology (ASH). Aplastic Anemia – Clinical Resources.

Keywords:

aplastic anemia, aplastic anemia symptoms, aplastic anemia causes, aplastic anemia diagnosis, aplastic anemia treatment, bone marrow failure, pancytopenia, hypocellular bone marrow, acquired aplastic anemia, inherited aplastic anemia, Fanconi anemia, severe aplastic anemia, very severe aplastic anemia, aplastic anemia prognosis, immunosuppressive therapy in aplastic anemia, ATG cyclosporine treatment, eltrombopag aplastic anemia, bone marrow transplant aplastic anemia, hematopoietic stem cell failure, bone marrow biopsy aplastic anemia, neutropenia infections aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia bleeding aplastic anemia, autoimmune aplastic anemia, viral hepatitis–associated aplastic anemia, aplastic anemia differential diagnosis, aplastic anemia guidelines, Dr Moustafa Abdou, Ask Hematologist

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now