Megaloblastic Anemias

Bone marrow aspirate demonstrating classic megaloblasts in megaloblastic anemia, showing nuclear–cytoplasmic asynchrony and enlarged erythroid precursors.

Introduction:

Megaloblastic anemias represent a spectrum of disorders caused by impaired DNA synthesis affecting all rapidly dividing hematopoietic cells, not only the erythroid lineage. When DNA replication is disrupted, the cell cycle cannot progress normally from the G2 phase to mitosis, resulting in continued cytoplasmic growth without division. This nuclear–cytoplasmic asynchrony produces the hallmark morphological features of macrocytosis and megaloblastosis. Consequently, the bone marrow releases unusually large, structurally abnormal, and immature red blood cells—known as megaloblasts.

Macrocytosis refers to an increased red cell size, typically defined by a mean cell volume (MCV) > 100 fL. Because macrocytosis has a broad differential—ranging from benign causes to serious hematologic disease—a targeted diagnostic evaluation is essential. Although it can occur at any age, macrocytosis is more common in older adults owing to the increased prevalence of its underlying etiologies.

The most frequent cause of megaloblastic anemia is defective DNA synthesis due to vitamin deficiency, specifically vitamin B12 (cobalamin) and folate. The pathologic state of megaloblastosis is characterized by large, immature, dysfunctional erythroid precursors in the bone marrow, accompanied by hypersegmented neutrophils—typically defined as neutrophils with five or more lobes—readily identifiable on the peripheral blood film. These features are considered classic and highly suggestive of megaloblastic hematopoiesis.

Peripheral blood smear showing a hypersegmented neutrophil in vitamin B12 deficiency, a classic marker of megaloblastic anemia.

Causes:

Folate deficiency:

- Nutritional deficiency (especially common at the extremes of age, in alcoholics, and in individuals with poor dietary intake of leafy vegetables and fortified cereals).

- Malabsorption (absorbed mainly in the upper jejunum): gastrectomy, coeliac disease/tropical sprue, extensive Crohn’s disease, and phenytoin, which interferes with enteric folate uptake.

- Increased requirements: including pregnancy, lactation, rapid growth in infancy or adolescence, chronic hemolysis, malignancies, and repeated dialysis leading to folate loss.

- Defective folate utilization: seen with antifolate drugs (e.g., methotrexate), certain anticonvulsants, and chronic alcohol excess, all of which impair folate metabolism.

B12 deficiency:

Vitamin B12 occurs naturally in foods derived from animals. Normally, vitamin B12 is absorbed in the terminal ileum, but only after binding to intrinsic factor, a gastric protein essential for its uptake. Any defect in this pathway can result in significant B12 deficiency and megaloblastic anemia.

Malabsorption:

- Pernicious anemia of immune origin leading to autoimmune destruction of parietal cells and failure of intrinsic factor production.

- Intrinsic factor deficiency secondary to stomach surgery (e.g., partial or total gastrectomy, bariatric surgery).

- Terminal ileal disease (site of B12 absorption), including Crohn’s disease, ileal resection, or radiation enteritis.

- Competitive parasites, especially bacterial overgrowth in “blind loops,” and Diphyllobothrium latum infection, both of which consume or bind B12.

- Pancreatic failure, reducing proteolytic activity needed to free B12 from its binding proteins.

- Occasional drugs that interfere with B12 handling or absorption.

Nutritional deficiency:

in vegans and alcoholics, particularly in those with prolonged dietary restriction or poor overall intake.

Toxins and Drugs:

Methotrexate, cytosine arabinoside, phenytoin, 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, trimethoprim, and alcohol. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib and imatinib have also been shown to induce macrocytosis in patients with renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and breast cancer, likely through effects on erythroid precursor maturation.

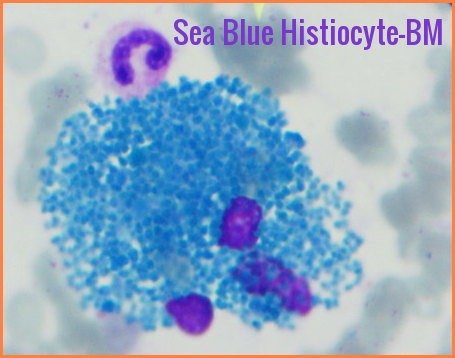

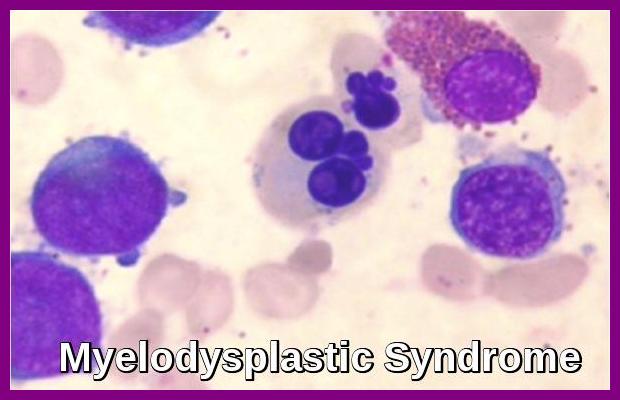

Refractory anemias of the following types may cause macrocytosis:

- Myelodysplastic anemias

- Myelophthisic anemias (marrow replacement by neoplasm, granuloma, or fibrosis)

- Aplastic anemia

- Acquired sideroblastic anemia

Rare causes:

certain inborn errors of metabolism and copper deficiency, the latter often resulting from excess zinc intake leading to competitive inhibition of copper absorption.

Clinical features:

Very insidious onset of anemia, often developing gradually over months due to impaired DNA synthesis and ineffective erythropoiesis.

Hemoglobin (Hb) may be profoundly reduced and can present with levels as low as 2 g/dL in severe megaloblastic anemia.

Anorexia (loss of appetite) and glossitis (smooth, sore, or beefy-red tongue) are common mucosal manifestations, reflecting rapid turnover of epithelial cells.

There may be fever, recurrent infections, and petechiae (tiny areas of bleeding on the skin or mucous membranes) in severe cases due to associated leukopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord can occur with severe B12 deficiency, leading to peripheral neuropathy, impaired vibration and proprioception, ataxia, and potentially irreversible neurological damage if untreated.

Atrophic glossitis with smooth, erythematous papillae-deficient tongue, a classic mucosal feature of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency in megaloblastic anemia.

Depigmented patches of vitiligo on the hands, an autoimmune condition commonly associated with pernicious anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency.

Investigations:

Low Hemoglobin with a raised MCV. In the early stages, macrocytosis appears before the anemia, making MCV elevation an early diagnostic clue.

The red cells show anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, and may contain inclusion bodies such as Howell–Jolly bodies, reflecting impaired DNA synthesis and ineffective erythropoiesis.

The neutrophil count is often reduced, and multisegmented (hypersegmented) neutrophils are characteristic early markers of megaloblastic anemia.

The platelet count is often reduced, contributing to bleeding manifestations in advanced disease.

Indirect bilirubin level may be elevated in pernicious anemia due to intramedullary hemolysis and increased breakdown of ineffective erythroid precursors.

The serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentration usually is markedly increased in pernicious anemia, often disproportionately high relative to the degree of anemia.

Intrinsic factor (IF) antibodies, type 1 and type 2, occur in up to 50% of patients with pernicious anemia and are highly specific for this autoimmune disorder.

Anti-parietal cell antibodies (APCA) are an advantageous tool for screening for autoimmune atrophic gastritis and pernicious anemia, although they are less specific than IF antibodies.

The bone marrow is hypercellular with megaloblastic changes in both the red and white cell series, demonstrating nuclear–cytoplasmic asynchrony and giant metamyelocytes.

Bone marrow aspirate showing classic megaloblasts with nuclear–cytoplasmic asynchrony, a hallmark feature of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency.

Treatment:

Treat any underlying cause if possible, including malabsorption syndromes, autoimmune gastritis, dietary deficiency, or medication-related interference with DNA synthesis.

Replace deficient hematinics:

Vitamin B12 is given by intramuscular injection (IM). The recommended regimen is 1 mg hydroxocobalamin IM three times weekly for 2 weeks (or on alternate days if neurological symptoms are present). Once hematologic recovery is achieved, maintenance therapy consists of 1 mg IM every 2–3 months for life in pernicious anemia or irreversible malabsorption.

Folate should not be given in untreated B12 deficiency, as isolated folate replacement may exacerbate or unmask neurological complications by supporting hematopoiesis without correcting the underlying cobalamin deficit. Folate 5 mg daily is usually given orally, even in malabsorption, because high-dose folic acid achieves adequate serum levels in most patients.

If B12 and folate deficiency coexist, correct B12 deficiency first to prevent progression of subacute combined degeneration and other irreversible neurological damage.

Nutritional Advice:

Foods rich in B12 (Cobalamin):

- Sardines

- Salmon

- Tuna

- Cod

- Shrimp and shellfish (e.g., clams, oysters)

- Lamb

- Beef

- Liver (especially beef liver — one of the richest sources)

- Yogurt

- Cow’s milk and dairy products

- Eggs

- Fortified cereals and fortified plant-based milks (especially important for vegetarians and vegans)

Vitamin B12 is found naturally only in animal-derived foods, so fortified foods or supplements may be needed for people with restricted diets or absorption issues.

Foods rich in folate (vitamin B9):

- Lentils

- Pinto beans

- Garbanzo beans (chickpeas)

- Asparagus

- Spinach and other leafy greens

- Navy beans

- Black beans

- Kidney beans

- Turnip greens

- Broccoli

- Citrus fruits (e.g., oranges) and other fruits (e.g., papaya, bananas)

- Fortified grains and cereals

Folate is abundant in legumes, leafy greens, and some fruits; however, natural folate may be partially lost during cooking, and fortified foods help reliably increase intake.

Clinical & Dietary Tips:

For people at high risk of deficiency (e.g., older adults, vegans, post-gastrectomy), diet alone may be insufficient — consider clinical supplementation after testing.

Fortified foods (cereals, nutritional yeast, fortified milks) can be especially valuable sources of B12 for non-meat eaters.

Consuming a varied diet including both B12 and folate sources supports optimal red blood cell production and DNA synthesis.

Questions and Answers:

What is megaloblastic anemia and what causes it?

Megaloblastic anemia is a macrocytic anemia caused by impaired DNA synthesis, most commonly due to vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. It produces classic features such as megaloblasts in the bone marrow, macro-ovalocytes, and hypersegmented neutrophils on the blood film.

What are the early signs of megaloblastic anemia?

Early signs include fatigue, pallor, loss of appetite, glossitis, and mild macrocytosis that often appears before anemia becomes severe. Hypersegmented neutrophils may be one of the earliest detectable abnormalities on the peripheral smear.

How does vitamin B12 deficiency lead to neurological symptoms?

Vitamin B12 deficiency disrupts myelin synthesis, resulting in neuropathy, impaired proprioception, ataxia, and potentially subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord if untreated.

What do megaloblasts look like on bone marrow examination?

Megaloblasts appear as large erythroid precursors with open chromatin and pronounced nuclear–cytoplasmic asynchrony. Giant metamyelocytes may also be present, reflecting defective DNA synthesis across all marrow lineages.

What are hypersegmented neutrophils and why are they important?

Hypersegmented neutrophils are neutrophils with more than five nuclear lobes. They are a hallmark of megaloblastic hematopoiesis and often appear before anemia becomes clinically significant, making them highly sensitive indicators of B12 or folate deficiency.

What oral findings suggest vitamin B12 or folate deficiency?

Atrophic glossitis, characterized by a smooth, erythematous tongue with loss of papillae, is a common mucosal manifestation of megaloblastic anemia and often accompanies nutritional deficiency.

How is pernicious anemia diagnosed?

Pernicious anemia is diagnosed through evidence of vitamin B12 deficiency along with intrinsic factor antibodies or anti-parietal cell antibodies, often accompanied by elevated LDH, indirect bilirubin, and macrocytosis.

Can megaloblastic anemia cause very low hemoglobin levels?

Yes, in severe, prolonged, or untreated cases, hemoglobin may fall to critically low levels due to ineffective erythropoiesis and intramedullary hemolysis, although such profound anemia is uncommon in modern clinical practice.

What laboratory findings are typical in megaloblastic anemia?

Laboratory results commonly show increased MCV, low hemoglobin, hypersegmented neutrophils, low B12 or folate levels, elevated LDH, raised indirect bilirubin, and pancytopenia in advanced cases. Bone marrow typically reveals hypercellularity with megaloblastic changes.

Why must folate not be given alone in vitamin B12 deficiency?

Folate supplementation alone can correct anemia but will not treat the neurological complications of B12 deficiency and may allow them to progress unnoticed, potentially leading to irreversible neurological damage.

Which foods are best for boosting vitamin B12 and folate levels?

Vitamin B12–rich foods include fish, meat, dairy, and fortified cereals. Folate-rich foods include lentils, leafy greens, beans, and fortified grains. These dietary sources help support normal red blood cell production and prevent megaloblastic changes.

What conditions are associated with vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anemia?

Associated autoimmune conditions include vitiligo, autoimmune thyroid disease, and atrophic gastritis.

References:

Antony AC. Megaloblastic Anemias. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr., Silberstein LE, Heslop HE, Weitz JI, Anastasi J. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2013:473-504.

Hoffbrand AV. Megaloblastic Anemias. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015.

Wang YH, Yan F, Zhang WB, et al. An investigation of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly inpatients in neurology department. Neurosci Bull. 2009;25(4):209-215.

Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

Schallier D, Trullemans F, Fontaine C, Decoster L, De Greve J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced macrocytosis. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(12):5225-5228.

O’Leary F, Samman S. Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients. 2010;2(3):299-316. doi:10.3390/nu2030299.

National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH ODS). Vitamin B12 Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional

National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH ODS). Folate Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Folate-HealthProfessional

Cleveland Clinic. Megaloblastic Anemia: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23160-megaloblastic-anemia

Mayo Clinic Staff. Vitamin B12 deficiency: Causes, symptoms, and treatment. Mayo Clinic. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org

Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:149-160.

O’Broin S, Kelleher B. Microbiological assay for folate: influence of folate derivatives and ultrafiltration on assay performance. Clin Chem. 1992;38(11):2191-2195.

Keywords:

megaloblastic anemia, macrocytic anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, pernicious anemia, hypersegmented neutrophils, megaloblasts, macro-ovalocytes, megaloblastic hematopoiesis, subacute combined degeneration, B12 malabsorption, intrinsic factor antibodies, autoimmune gastritis, atrophic glossitis, vitiligo B12 deficiency, bone marrow megaloblasts, macrocytosis causes, nuclear cytoplasmic asynchrony, elevated MCV, high LDH anemia, intramedullary hemolysis, folate rich foods, vitamin B12 foods, Cleveland Clinic nutrition anemia, NIH ODS vitamin B12, folate nutrition, B12 neurological symptoms, B12 injection regimen, hydroxocobalamin treatment, macrocytosis evaluation, myelodysplastic anemia macrocytosis, tyrosine kinase inhibitor macrocytosis, diet and blood health

Great information. It will be very helpful for me. Thanks.

Hello, Dr., this is a very helpful article. Thank you!

I have a question: do we consider a Hb concentration of 15g/dl as a normal value even if it is for a patient with hemoglobinopathies like thalassemia or sickle cell?!

Hi Untierson,

Thank you for your comment.

A Hb of 15g/L is unusually high in a patient with hemoglobinopathy even if he/she is a carrier.

I would suggest repeating the test after maintaining adequate hydration for a few weeks.

Also, ensure that there are no other underlying factors of hypoxemia like smoking, lung disease, heart disease, etc.

BW,