Malaria

Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic infection caused by protozoa of the Plasmodium genus and transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. Once introduced into the bloodstream, the parasite completes a sexual cycle within the mosquito and recurrent asexual cycles in humans, leading to the development of characteristic clinical symptoms. Gametocytes formed in human hosts perpetuate transmission, making malaria a major global public health challenge with significant morbidity and mortality.

Clinical features:

- The initial incubation period of malaria is 9-11 days.

- Malaria symptoms include fever, shaking chills, body aches, cough, headache, anemia, fatigue, malaise, and splenomegaly. The fever is often periodic, the frequency in part reflecting the species of Plasmodium.

- In severe cases especially of the malignant tertian form (P. falciparum), there may be hemolysis, thromboses, shock, and cerebral complications.

It was demonstrated in the late eighties and early nineties that those with O type blood group are protected from severe or fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria compared with non-O blood groups (A, B, and AB) by the mechanism of inducing high levels of anti-malarial IgG antibodies.

Investigations:

During an acute episode of malaria, there may be anemia and plasmodial forms can be detected in the peripheral blood especially on thick and thin blood films. Differentiation of the different species require considerable expertise but is important as together with the geographical source of origin, this will influence the choice of therapy. Note that 1 negative smear does not exclude malaria as a diagnosis; several more smears should be examined over a 36-hour period.

Specific tests for malaria infection should be also carried out e.g. Microhematocrit centrifugation and Fluorescent dyes/ultraviolet indicator tests.

Fewer than 5% of malaria patients have leucocytosis; thus, if leucocytosis is present, the differential diagnosis should be broadened!

If the patient is to be treated with primaquine, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) level should be checked.

Plasmodium Falciparum

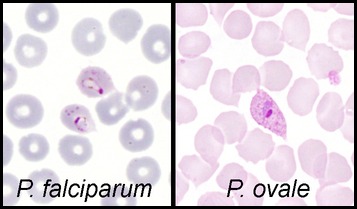

Peripheral blood smear showing the characteristic banana-shaped gametocyte of Plasmodium falciparum in malaria.

Parasites may be scanty, but red cells super-infected with trophozoites may be seen. Infected RBCs are round, of normal size and Schuffner’s dots are not seen. The gametocytes are typically elongated or banana-shaped.

Plasmodium Vivax

Peripheral blood smear showing Plasmodium vivax trophozoites with enlarged, pale erythrocytes typical of vivax malaria.

Ring forms (trophozoites) and segmented schizonts may be seen. The schizonts may develop into free merozoites or into round sexual forms (gametocytes).

The invaded red cells are increased in size and contain Schuffner’s dots.

Plasmodium Ovale

Comparison blood smear showing Plasmodium falciparum ring forms alongside the enlarged, oval erythrocytes typical of Plasmodium ovale malaria.

The appearances in the blood are similar to Plasmodium Vivax except that the gametocytes and infected red cells are often oval with fimbriated edges. Schuffner’s dots are conspicuous.

Plasmodium Malariae

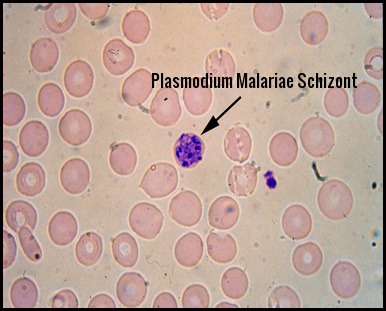

Peripheral blood smear demonstrating the classic rosette-pattern schizont of Plasmodium malariae in malaria.

In this form, the trophozoites are often band-shaped. The infested red cells are not enlarged and there are no Schuffner’s dots.

N.B. It should be noted that mixed infections can occur.

Prophylaxis:

Blood type, metabolism, exercise, shirt color and even drinking beer can make individuals especially delicious to mosquitoes! Mosquitoes bite us to harvest proteins from our blood—research shows that they find certain blood types more appetizing than others. One study found that in a controlled setting, mosquitoes landed on people with Type O blood nearly twice as often as those with Type A. People with Type B blood fell somewhere in the middle of this itchy spectrum. Additionally, based on other genes, about 85 percent of people secrete a chemical signal through their skin that indicates which blood type they have, while 15 percent do not, and mosquitoes are also more attracted to secretors than nonsecretors regardless of which type they are.

Prophylaxis involves mosquito control, avoidance of bites and appropriate prophylactic drug therapy. Avoid mosquitoes by limiting exposure during times of typical blood meals (ie, dawn, dusk). Wearing long-sleeved clothing and using insect repellants may also prevent infection. Avoid wearing perfumes and colognes.

Considerations when choosing a drug for malaria prophylaxis:

- Recommendations for drugs to prevent malaria differ by country of travel and can be found in the country-specific tables of the Yellow Book. Recommended drugs for each country are listed in alphabetical order and have comparable efficacy in that country.

- No antimalarial drug is 100% protective and must be combined with the use of personal protective measures, (i.e., insect repellent, long sleeves, long pants, sleeping in a mosquito-free setting or using an insecticide-treated bednet).

- For all medicines, also consider the possibility of drug-drug interactions with other medicines that the person might be taking as well as other medical contraindications, such as drug allergies.

- When several different drugs are recommended for an area, the following information might help in the decision process:

Atovaquone/Proguanil (Malarone):

Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Some people prefer to take daily medicine.

Good choice for shorter trips because you only have to take the medicine for 7 days after traveling rather than 4 weeks. Very well-tolerated medicine – side effects uncommon.

Pediatric tablets are available and may be more convenient. However, cannot be used by women who are pregnant or breastfeeding a child less than 5 kg, cannot be taken by people with severe renal impairment, tends to be more expensive than some of the other options (especially for trips of long duration). Some people (including children) would rather not take medicine every day.

Chloroquine:

Some people would rather take medicine weekly. Good choice for long trips because it is taken only weekly. Some people are already taking hydroxychloroquine chronically for rheumatologic conditions. In those instances, they may not have to take additional medicine. Can be used in all trimesters of pregnancy. However, cannot be used in areas with chloroquine or mefloquine resistance, may exacerbate psoriasis. Some people would rather not take a weekly medication. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel. Not a good choice for last-minute travelers because drug needs to be started 1-2 weeks prior to travel.

Doxycycline:

Some people prefer to take daily medicine. Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Tends to be the least expensive antimalarial. Some people are already taking doxycycline chronically for prevention of acne. In those instances, they do not have to take additional medicine. Doxycycline also can prevent some additional infections (e.g., Rickettsiae and leptospirosis) and so it may be preferred by people planning to do lots of hiking, camping, and wading and swimming in freshwater. However, cannot be used by pregnant women and children <8 years old. Some people would rather not take medicine every day. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel. Women prone to getting vaginal yeast infections when taking antibiotics may prefer taking a different medicine. Persons planning on considerable sun exposure may want to avoid the increased risk of sun sensitivity. Some people are concerned about the potential of getting an upset stomach from doxycycline.

Mefloquine (Lariam):

Some people would rather take medicine weekly. Good choice for long trips because it is taken only weekly. Can be used during pregnancy. However, cannot be used in areas with mefloquine resistance. Cannot be used in patients with certain psychiatric conditions. Cannot be used in patients with a seizure disorder. Not recommended for persons with cardiac conduction abnormalities. Not a good choice for last-minute travelers because the drug needs to be started at least 2 weeks prior to travel. Some people would rather not take a weekly medication. For trips of short duration, some people would rather not take medication for 4 weeks after travel.

Primaquine:

It is the most effective medicine for preventing P. vivax and so it is a good choice for travel to places with > 90% P. vivax. Good choice for shorter trips because you only have to take the medicine for 7 days after traveling rather than 4 weeks. Good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs. Some people prefer to take daily medicine. However, cannot be used in patients with glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Cannot be used in patients who have not been tested for G6PD deficiency. There are costs and delays associated with getting a G6PD test done; however, it only has to be done once. Once a normal G6PD level is verified and documented, the test does not have to be repeated the next time primaquine is considered. Cannot be used by pregnant women. Cannot be used by women who are breastfeeding unless the infant has also been tested for G6PD deficiency. Some people (including children) would rather not take medicine every day. Some people are concerned about the potential of getting an upset stomach from primaquine.

Treatment:

Early recognition and urgent treatment of malaria are critical, particularly in any febrile patient returning from a malaria-endemic region within the previous year—most importantly within the last three months. Malaria should remain high on the differential diagnosis even if chemoprophylaxis was taken, as no prophylactic regimen is fully protective. Delayed diagnosis significantly increases morbidity and mortality, especially in young children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised patients.

Management principles:

During the acute phase, patients should receive rest, adequate hydration, and supportive care. Antimalarial therapy is required to eradicate the asexual blood-stage parasites responsible for clinical disease. Dormant liver forms (hypnozoites) occur only in Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, necessitating specific eradication therapy; P. falciparum does not form hypnozoites.

Drug considerations:

Choice of antimalarial therapy must be guided by species identification, local drug-resistance patterns, and disease severity. P. falciparum is widely resistant to chloroquine, whereas resistance is uncommon in P. vivax, and P. ovale and P. malariae generally remain chloroquine-sensitive. For P. vivax and P. ovale, radical cure requires the addition of primaquine (or tafenoquine, where appropriate) to eliminate exoerythrocytic hypnozoites and prevent relapse. Treatment decisions should ideally be supervised by clinicians experienced in managing malaria, particularly in severe or complicated cases.

Summary:

Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic infection caused by Plasmodium species and transmitted through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease presents with recurrent fever, chills, sweats, anemia, and splenomegaly, and remains a major global health challenge in tropical and subtropical regions. Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic examination of peripheral blood films, detection of Plasmodium antigens, or molecular testing. Plasmodium falciparum is associated with severe malaria and high mortality, while P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi produce varying clinical patterns. Prompt recognition and treatment are essential, with therapy guided by parasite species, drug-resistance patterns, and disease severity. Chloroquine remains effective for P. malariae and most P. ovale infections, whereas P. falciparum requires alternative agents due to widespread resistance. Radical cure of P. vivax and P. ovale also includes primaquine to eliminate dormant liver hypnozoites. Effective prevention—mosquito control, insecticide-treated nets, chemoprophylaxis, and early diagnosis—remains key to reducing malaria-related morbidity and mortality.

Questions and Answers:

What is malaria and how is it transmitted?

Malaria is a parasitic infection caused by Plasmodium species and transmitted through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The parasite enters the bloodstream, multiplies in red blood cells, and causes recurrent fever and systemic illness.

What are the main symptoms of malaria?

Symptoms include cyclical fever, chills, sweats, headache, myalgia, nausea, fatigue, anemia, and splenomegaly. Plasmodium falciparum infections may progress rapidly to severe malaria with organ dysfunction.

How is malaria diagnosed on a blood smear?

Diagnosis is confirmed by identifying Plasmodium parasites on thick and thin peripheral blood films. Characteristic findings vary by species, including delicate ring forms in P. falciparum, enlarged stippled erythrocytes in P. vivax and P. ovale, and rosette schizonts in P. malariae.

Which Plasmodium species cause malaria in humans?

The five species causing human malaria are P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi. P. falciparum is associated with severe disease and the highest mortality.

Why is Plasmodium falciparum considered the most dangerous species?

P. falciparum can infect red cells of all ages, leading to high parasitemia, severe anemia, microvascular obstruction, cerebral malaria, metabolic acidosis, and multi-organ failure, making it the most lethal species globally.

How does Plasmodium vivax differ from Plasmodium falciparum?

P. vivax typically infects reticulocytes, causing enlarged erythrocytes and Schüffner’s stippling, and forms dormant liver hypnozoites that can relapse. P. falciparum does not form hypnozoites and often produces multiple ring forms in a single red cell.

Do Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium vivax form hypnozoites?

Yes. Both P. vivax and P. ovale form dormant liver hypnozoites that can reactivate months or years later, requiring primaquine to prevent relapse; this does not occur in P. falciparum.

What is the characteristic feature of Plasmodium malariae on blood film?

P. malariae often shows band-form trophozoites and classical rosette-pattern schizonts containing merozoites arranged around a central pigment mass.

How is malaria treated?

Treatment depends on species and severity. P. falciparum requires non-chloroquine therapy due to widespread resistance. P. vivax and P. ovale need primaquine for radical cure of hypnozoites. Supportive care with fluids and monitoring is essential in all patients.

Why is prompt treatment of malaria important?

Delayed therapy increases the risk of complications such as severe anemia, cerebral malaria, acidosis, renal failure, and death. Early treatment greatly improves outcomes and prevents transmission.

How can malaria be prevented during travel?

Prevention includes chemoprophylaxis appropriate to the destination, use of insecticide-treated bed nets, mosquito repellents, protective clothing, and prompt evaluation of any fever after returning from an endemic area.

What are the typical blood-film features of Plasmodium falciparum?

Blood smears show multiple delicate ring forms per erythrocyte, appliqué forms, and banana-shaped gametocytes; schizonts are rarely seen in peripheral blood.

What does a Plasmodium vivax trophozoite look like?

Trophozoites of P. vivax appear ameboid within enlarged pale erythrocytes, often with Schüffner’s stippling, helping distinguish it from other species.

How do Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium ovale differ on microscopy?

P. falciparum shows small ring forms and banana-shaped gametocytes, whereas P. ovale infects enlarged oval erythrocytes with stippling and fimbriated edges.

References:

Kobayashi T, Gamboa D, Ndiaye D, et al. Malaria diagnosis across the International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research: platforms, performance, and standardization. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(3 Suppl):99–109. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0004.

Smith AD, Bradley DJ, Smith V, et al. Imported malaria and high-risk groups: observational study using UK surveillance data, 1987–2006. BMJ. 2008;337:a120. doi:10.1136/bmj.a120.

Day N. Malaria. In: Eddleston M, et al., editors. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 31–65.

Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE. Plasmodium species (malaria). In: Mandell GL, et al., editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. p. 3437–3462.

American Public Health Association. Malaria. In: Heymann DL, editor. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 19th ed. Washington, DC: APHA; 2008. p. 373–393.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Choosing a drug to prevent malaria. Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/drugs.html. Updated November 9, 2012.

Nasr A, Eltoum M, Yassin A, ElGhazali G. Blood group O protects against complicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria through enhanced anti-malarial IgG production. Saudi J Health Sci. Available at: https://goo.gl/7SW1TJ.

Stromberg J. Why do mosquitoes bite some people more than others? Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-do-mosquitoes-bite-some-people-more-than-others-10255934/.

Keywords:

malaria, malaria symptoms, malaria diagnosis, malaria treatment, malaria prevention, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium knowlesi, malaria blood film, malaria ring forms, falciparum gametocyte, vivax trophozoite, malaria schizont, Anopheles mosquito, malaria transmission, malaria life cycle, malaria complications, severe malaria, cerebral malaria, malaria microscopy, malaria parasitemia, malaria prophylaxis, malaria drugs, chloroquine resistance, primaquine hypnozoites, travel-related malaria, imported malaria, febrile traveler malaria, malaria vector control, mosquito bite prevention, malaria endemic regions, malaria mortality risk

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now