Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is an infectious disease caused by intracellular protozoan parasites of the Leishmania genus, transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female sand flies. The condition occurs across several endemic regions worldwide and can present in cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral forms.

Global epidemiology of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis – WHO world map showing endemic regions and reported case numbers for 2022.

More than 20 Leishmania species are capable of causing human disease; although they appear morphologically similar, they are distinguishable through specialised laboratory techniques. Transmission occurs when sand flies inject motile promastigotes into the skin, initiating infection within host macrophages.

The clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis ranges from a self-resolving cutaneous ulcer to a mutilating mucocutaneous disease and even to lethal systemic illness. Therapy has long been a challenge in the more severe forms of the disease, and it is made more difficult by the emergence of drug resistance.

Pathophysiology:

After inoculation by a sandfly, promastigotes are phagocytized by host macrophages; inside these cells, they transform into amastigotes.

The parasites may remain localized in the skin or spread to internal organs or the mucosa of the nasopharynx, resulting in 3 major clinical forms of leishmaniasis:

- Cutaneous

- Mucosal

- Visceral

Clinical features:

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis:

In cutaneous leishmaniasis, a well-demarcated skin lesion develops at the site of a sandfly bite, usually within several weeks to months. Multiple lesions may occur after multiple infective bites or with metastatic spread. Their appearance varies.

The initial lesion is often a papule that slowly enlarges, ulcerates centrally, and develops a raised, erythematous border where intracellular parasites are concentrated. Ulcers are typically painless and cause no systemic symptoms unless secondarily infected. Lesions usually heal spontaneously after several months but may persist for years. They leave a depressed, burn-like scar. The course depends on the infecting Leishmania species and the host’s immune status.

Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis:

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis consists of the relentless destruction of the oropharynx and nose, resulting in extensive midfacial destruction. The disease starts with a primary cutaneous ulcer. This lesion heals spontaneously, but progressive mucosal lesions develop months to years later. Typically, patients have nasal stuffiness, discharge, and pain. Over time, the infection may progress, resulting in gross mutilation of the nose, palate, or face.

Visceral Leishmaniasis:

In visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar), the clinical manifestations usually develop gradually over weeks to months after inoculation of the parasite but can be acute. Irregular fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia with a reversed albumin:globulin ratio occur. In some patients, there are twice-daily temperature spikes. Cutaneous skin lesions rarely occur. Emaciation and death occur within months to years in patients with progressive infections. Those with asymptomatic, self-resolving infections and survivors (after successful treatment) are resistant to further attacks unless cell-mediated immunity is impaired (eg, by AIDS). Relapse may occur years after the initial infection.

Visceral Leishmaniasis (kala-azar) – clinical illustration of significant hepatosplenomegaly in an affected child.

Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis:

Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) develops months to years after the patient’s recovery from visceral leishmaniasis, with cutaneous lesions ranging from hypopigmented macules to erythematous papules and from nodules to plaques; the lesions may be numerous and persist for decades. PKDL lesions are thought to be a reservoir for the spread of infection in endemic countries.

Post kala-azar dermal Leishmaniasis – characteristic papular and nodular facial lesions following treatment of visceral disease.

Diagnosis:

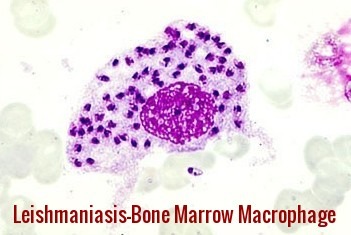

- A definite diagnosis is made by demonstrating organisms in Giemsa-stained smears, by isolating Leishmania in cultures, or by PCR-based assays of aspirates from the spleen, bone marrow, liver, or lymph nodes in patients with visceral leishmaniasis or of biopsy, aspirates, or touch preparations from a skin lesion. Parasites are usually difficult to find or isolate in biopsies of mucosal lesions.

Leishmaniasis bone marrow macrophage – numerous intracellular amastigotes seen in visceral (kala-azar) infection.

- Serologic tests can help diagnose visceral leishmaniasis; high titers of antibodies to a recombinant leishmanial antigen (rk39) are present in most immunocompetent patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Antibodies may be absent in patients with AIDS or other immunocompromising conditions. Serologic tests for antileishmanial antibodies are not helpful in the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

- The leishmanin skin test is not available in the US. It is typically positive in patients with cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis but negative in those with active visceral leishmaniasis.

Prevention and Control:

No vaccines or drugs to prevent infection are available. The best way for travelers to prevent infection is to protect themselves from sand fly bites.

Avoid outdoor activities, especially from dusk to dawn, when sand flies generally are the most active.

When outdoors (or in unprotected quarters):

- Minimize the amount of exposed (uncovered) skin. To the extent that is tolerable in the climate, wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks; and tuck your shirt into your pants.

- Apply insect repellent to exposed skin and under the ends of sleeves and pant legs. The most effective repellents generally are those that contain the chemical DEET (N,N-diethylmetatoluamide).

When indoors:

- Stay in well-screened or air-conditioned areas.

- Keep in mind that sand flies are much smaller than mosquitoes and therefore can get through smaller holes.

- Spray living/sleeping areas with an insecticide to kill insects.

- If you are not sleeping in a well-screened or air-conditioned area, use a bed net and tuck it under your mattress. If possible, use a bed net that has been soaked in or sprayed with a pyrethroid-containing insecticide. The same treatment can be applied to screens, curtains, sheets, and clothing (clothing should be retreated after five washings).

Treatment:

The choice of treatment depends on the geographical region where the disease was acquired, the specific Leishmania species involved, and the clinical form of infection.

For visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) in India, South America, and the Mediterranean, liposomal amphotericin B remains the recommended first-line therapy and is frequently administered as a single high-dose regimen, achieving cure rates of up to 95% in some studies. In India, widespread resistance has rendered pentavalent antimonials largely ineffective, making amphotericin-based regimens essential.

In several regions of East Africa, a combination of pentavalent antimonials and paromomycin is advised, though toxicity—including pancreatitis, hepatotoxicity, and cardiac conduction disturbances—remains a significant limitation. Paromomycin alone is also used as an alternative in selected settings.

Miltefosine, an oral agent, is effective against both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis and offers the advantage of outpatient therapy. Its teratogenicity requires strict pregnancy avoidance for at least three months after treatment, and emerging resistance underscores the need for careful stewardship.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis:

Cutaneous ulcers frequently heal spontaneously; however, treatment accelerates epithelialisation, reduces scarring, and prevents dissemination to mucosal sites, particularly in species with mucocutaneous potential (L. braziliensis complex). Facial lesions, function-threatening ulcers, or cosmetically disfiguring wounds may also warrant plastic or reconstructive surgical intervention.

Therapeutic options include:

- Local therapies such as intralesional antimonials, cryotherapy, thermotherapy, and topical paromomycin.

- Systemic therapy (e.g., miltefosine, amphotericin B, or antimonials) when lesions are multiple, large, or associated with high-risk species.

Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis:

This form typically requires systemic therapy, often with liposomal amphotericin B or miltefosine, due to its destructive potential and risk of progressive mucosal involvement.

Relapse and Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL):

PKDL may emerge months to years after treating visceral disease. Management often involves liposomal amphotericin B or prolonged miltefosine therapy, depending on regional guidelines and severity.

Summary:

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease caused by Leishmania species transmitted through the bite of infected female sand flies. The condition presents in three major forms — cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral (kala-azar) — each with distinct clinical manifestations ranging from localized skin ulcers to destructive mucosal disease and life-threatening hepatosplenomegaly. Endemic in parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, Leishmaniasis remains a significant global health burden. Diagnosis relies on identifying amastigotes in tissue samples, serology, or molecular testing, while management includes antimonial agents, amphotericin B, miltefosine, and vector-control strategies. Understanding transmission patterns, early symptoms, and available treatments is essential for reducing morbidity and preventing progression, particularly in high-risk populations.

Questions and Answers:

What is Leishmaniasis and how is it transmitted?

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease caused by Leishmania species and transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female sand flies, leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral (kala-azar) forms depending on the species and host response.

What are the main types of Leishmaniasis?

The disease occurs in three major clinical forms: cutaneous leishmaniasis causing skin ulcers, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis affecting mucosal tissues, and visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) presenting with fever, weight loss, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly.

What are the early symptoms of visceral Leishmaniasis (kala-azar)?

Early symptoms include prolonged fever, fatigue, weight loss, abdominal distension from hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and susceptibility to secondary infections.

How is cutaneous Leishmaniasis identified clinically?

Cutaneous leishmaniasis presents with painless papules or nodules that evolve into well-defined ulcers with raised, indurated margins, typically appearing weeks after a sand-fly bite.

What does mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis look like?

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis causes destructive lesions of the nasal septum, oral mucosa, or pharynx, often starting months after a cutaneous infection with species such as L. braziliensis.

What is Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL)?

PKDL is a dermal complication that appears months to years after treating visceral leishmaniasis, presenting with papular, nodular, or hypopigmented lesions on the face and body, especially in endemic regions like India and Sudan.

How is Leishmaniasis diagnosed?

Diagnosis is made by identifying Leishmania amastigotes in tissue samples such as skin scrapings, bone marrow, or splenic aspirates, supported by PCR, serology, or culture depending on disease form and region.

What is the recommended treatment for visceral Leishmaniasis?

Liposomal amphotericin B is the preferred treatment for visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) in India, South America, and the Mediterranean, often given as a single high-dose regimen with excellent cure rates.

Why are antimonials no longer effective in India?

High levels of drug resistance in North-East India have rendered pentavalent antimonials largely ineffective for treating visceral leishmaniasis, necessitating amphotericin B–based regimens.

What are effective treatments for cutaneous Leishmaniasis?

Cutaneous lesions may heal spontaneously, but treatment options include topical paromomycin, intralesional antimonials, cryotherapy, thermotherapy, or systemic agents such as miltefosine depending on severity and species.

Is miltefosine effective for all types of Leishmaniasis?

Miltefosine is effective for both visceral and cutaneous disease, but its use is limited by teratogenicity and emerging resistance, requiring strict pregnancy-prevention guidelines.

Which regions have the highest burden of Leishmaniasis?

According to WHO epidemiology maps, major endemic regions include parts of South Asia, East Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Mediterranean, with varying species distribution and case numbers.

How can Leishmaniasis be prevented?

Prevention relies on reducing sand-fly exposure through insecticide-treated nets, repellents, protective clothing, and vector-control programs in endemic areas.

Why is kala-azar considered life-threatening?

Kala-azar is fatal if untreated due to progressive marrow suppression, severe organomegaly, malnutrition, and secondary infections, making early diagnosis and therapy essential.

Can Leishmaniasis relapse after treatment?

Yes, particularly visceral disease, where relapse may present as persistent fever or as PKDL, requiring reassessment and appropriate systemic therapy.

References:

World Health Organization (WHO). Leishmaniasis: the disease and its epidemiology. Available at: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/disease_epidemiology/en/ (Accessed 10 April 2014).

World Health Organization (WHO). The global epidemiology of Leishmaniasis. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis/the-global-epidemiology-of-leishmaniasis (Accessed 4 December 2025).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Leishmaniasis: epidemiology and risk factors. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/epi.html (Accessed 11 April 2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Leishmaniasis: prevention and control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/prevent.html (Accessed 4 December 2025).

McHugh CP, Melby PC, LaFon SG. Leishmaniasis in Texas: epidemiology and clinical aspects of human cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(5):547–555.

Eradication of Leishmaniasis from Yemen Project (ELYP), Regional Leishmaniasis Control Center (RLCC). Leishmaniasis in Yemen. Available at: https://rlccye.blogspot.com/2015/11/leishmaniasis-in-yemen.html (Accessed 4 December 2025).

Keywords:

Leishmaniasis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, visceral leishmaniasis, kala-azar, post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, PKDL, Leishmania donovani, Leishmania species, sand fly bite, sandfly vector, Leishmaniasis diagnosis, bone marrow amastigotes, Leishmaniasis treatment, liposomal amphotericin B, miltefosine, pentavalent antimonials, paromomycin, Leishmaniasis epidemiology, WHO Leishmaniasis map, global Leishmaniasis distribution, Leishmaniasis symptoms, Leishmaniasis prevention, Leishmaniasis complications, hepatosplenomegaly, Leishmaniasis ulcers, tropical parasitic infections, neglected tropical diseases, NTD Leishmaniasis, Leishmaniasis risk factors, Leishmaniasis endemic regions, Leishmaniasis clinical images, Leishmaniasis management guidelines

I cannot believe it. I had this from River Maya in Mexico, it developed several weeks after I returned. I was on a cocktail of antibiotics and creams which did nothing. I am left with scarring on my back, nose and face. It took a year to stop spreading and is now finally getting better18 months on.

I will have to see my gp now to let them know what it was and see if I need treatment.

Hi Ross,

Thank you for sharing your experience with us.

Best wishes,

Would you be interested to do a tour with me in the US?

The people of the world need to learn….physicians need to learn.

Thank you

This past week and I guess on and into the future now is my first adventure was these. It is April first 2025 and the first blossoming. And emergence of worms was a week ago. Since then, I’ve had multiple blossomings calling eruptions or emergences if I have them covered with a bandage or a hydrophone. Dressing They’re going and crawl into it, thinking it’s skin, and I can get ’em out one by warnies. You know, problem Is there’s light 70 to iche and 2 eggs in each blood clot? And I’ve got like 19 blood clots across both legs. Oh my God I can’t even get doctors to see me and look at me and take me seriously. Charlak disease is what I’d name it. They look like a f****** sarlac. Or whatever they called that one and doomed your pain is horrible as we try to cup them out. And flip those switch blades, and they just, they’re stubborn and God jeez, Christ, are they strong? I bet this step is stronger than Keller. How odd we have no more c. D, c, and we have no more inspections. We have no more investigations into this, killing them off. Nobody seems in the Portland area knows anything about him. I did a deep, deep deep rabbit hole diving. I’ve got myself a master’s course in today. It’s a fifth or sixth blossoming. I’ve lost track. I get to a day. I’m scared. I am scared and I do not scare easily. There’s a published report out somewhere, but morticians found structures. Just like the picture I’m gonna post down below. In the veins, in order of people who had taken the mrna virus, I’m not saying it causes it. I’m just saying what a strange coincidence. That these same fiber structures are found without any of the other symptoms.I’m scared

Hi Gypsy,

Thank you for reaching out and for sharing your experience.

I’m very sorry to hear about the distress you’re going through.

While your symptoms sound complex and concerning, I strongly encourage you to seek evaluation by a specialist in dermatology or infectious diseases for a thorough assessment.

If you’re struggling to access care locally, consider presenting to an emergency department.

I hope you’re able to get the help and clarity you need soon.

BW,

Dr M Abdou