Cryoglobulinemia

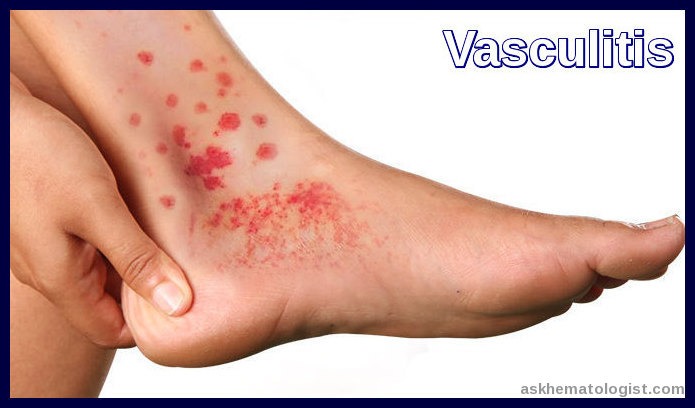

Lower-limb vasculitic changes in cryoglobulinemia, showing cold-induced inflammation and purpuric discoloration.

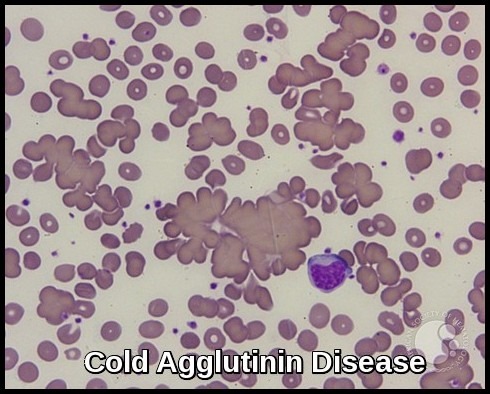

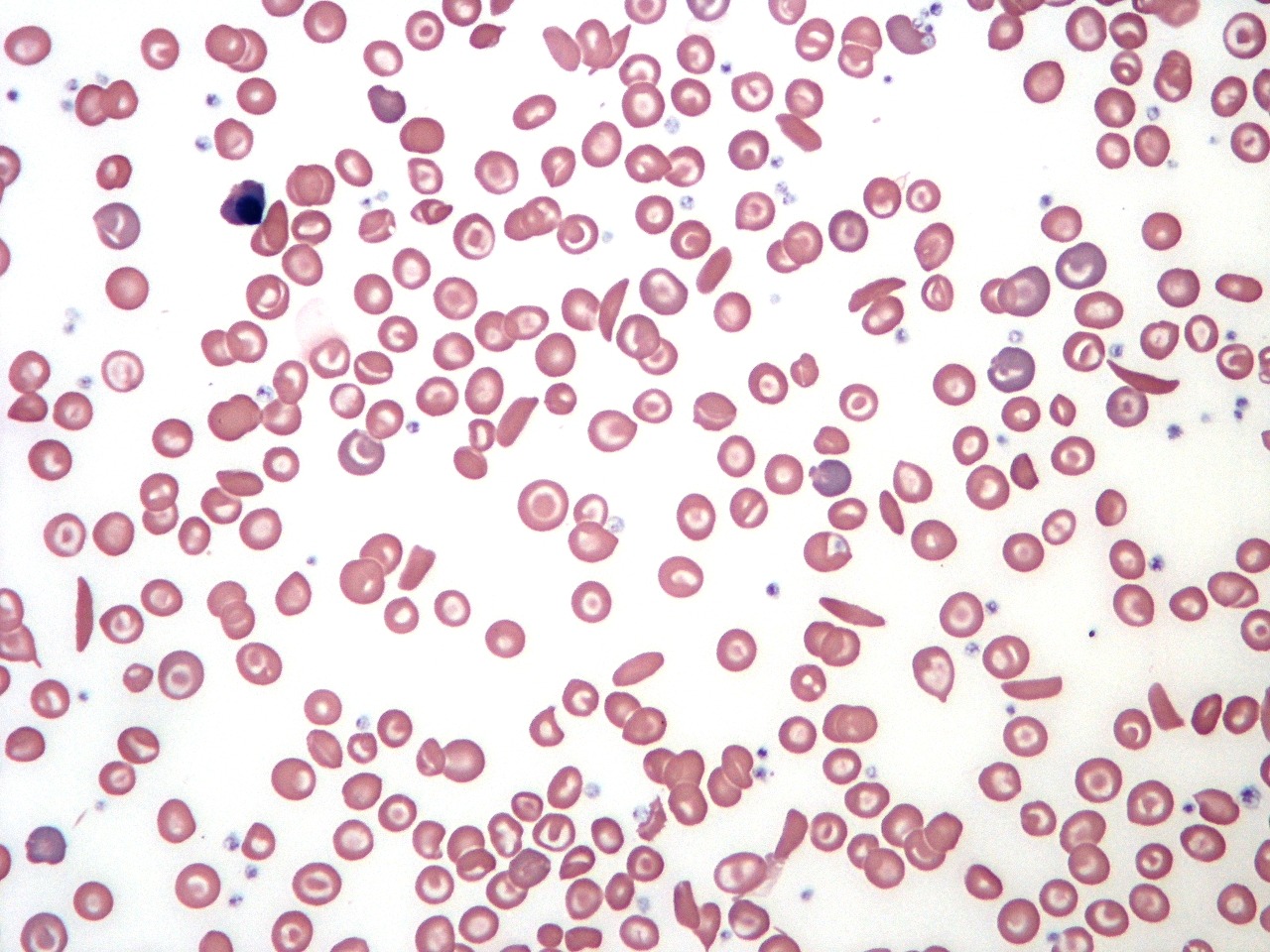

Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins—either monoclonal or mixed—that precipitate at low temperatures and resolubilize on warming, forming the basis of cryoglobulinemia. Although trace amounts may occur in some healthy individuals, clinically relevant cryoglobulinemia is typically associated with abnormal immunoglobulin production seen in autoimmune diseases, lymphoproliferative disorders, and chronic infections such as hepatitis C. When precipitated, cryoglobulins can increase blood viscosity and obstruct small vessels, resulting in tissue ischemia and systemic vasculitic features. This process is distinct from cold agglutinins, which cause red blood cell agglutination rather than immune-complex precipitation.

Cryoglobulinemia is a disorder characterized by the presence of elevated circulating cryoglobulins that precipitate in cold conditions and drive immune-complex–mediated disease. The condition is classified into three major types—type I (monoclonal), type II (mixed monoclonal–polyclonal), and type III (polyclonal)—each associated with distinct etiologies, including lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases, and chronic viral infections. The clinical presentation varies by cryoglobulin type and may involve vasculitis, neuropathy, arthralgia, or end-organ involvement.

When cryoglobulins are present in clinically significant concentrations, they can trigger systemic inflammation through the formation and deposition of cryoglobulin-containing immune complexes. This immune-complex vasculitis—central to mixed cryoglobulinemia—most commonly affects the kidneys and skin, leading to manifestations such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, palpable purpura, and ischemic complications. The severity of symptoms often correlates with cryocrit levels and underlying disease activity.

Classification:

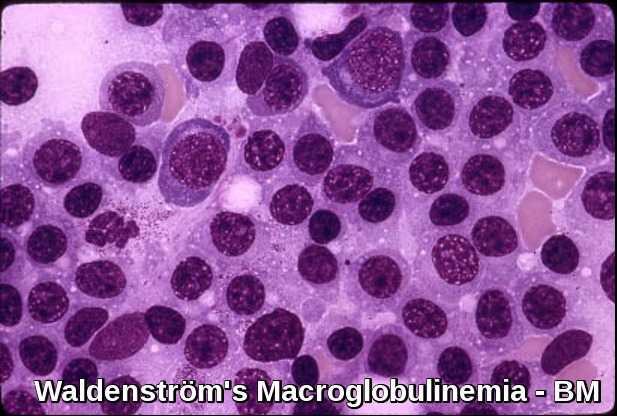

Cryoglobulinemia is classically grouped into three types according to the Brouet classification. Type I is most commonly encountered in patients with a plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Types II and III are strongly associated with infection by the hepatitis C virus. Type III is strongly associated with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Type I cryoglobulinemia, or simple cryoglobulinemia, is the result of a monoclonal immunoglobulin, usually immunoglobulin M (IgM) or, less frequently, immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A (IgA), or light chains.

Types II and III cryoglobulinemia (mixed cryoglobulinemia) contain rheumatoid factors (RFs), which are usually IgM and, rarely, IgG or IgA. Types II and III cryoglobulinemia represent 80% of all cryoglobulins.

Clinical features:

Raynaud’s phenomenon showing classic pallor, cyanosis, and reactive hyperemia, a vasospastic feature that may occur in cryoglobulinemia.

- Raynaud’s phenomenon with digital ulceration

- Acrocyanosis

- Vascular purpura and cutaneous vasculitis

- Livedo reticularis

- Myalgias and joint pains

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Arterial thrombosis

- Occasionally renal failure

Investigations:

Cryoprecipitate visible at 4°C and dissolved at 37°C, demonstrating the temperature-dependent precipitation characteristic of cryoglobulinemia.

- FBC, ESR, and Blood Film

- Renal profile

- LFTs

- Hepatitis profile and EBV serology

- Protein electrophoresis

- Rheumatoid factor, ANA, and Complement assay

- Cryoglobulin test: The sample is kept at body temperature (at 37°C) during preparation. The person’s serum is then refrigerated (at 4° C) for 72 hours and examined daily (up to 7 days) for precipitates. If there are any present, then the quantity is estimated and the sample is warmed to determine whether the precipitates dissolve. If they do, then cryoglobulins are present.

- Urinalysis

- Chest x-ray

- Skin biopsy

- Angiogram

- Nerve conduction studies

Treatment:

Asymptomatic cryoglobulinemia does not require treatment.

Avoidance of cold to treat mild cases.

Secondary cryoglobulinemia is best managed with treatment of the underlying malignancy or associated disease. Otherwise, cryoglobulinemia is treated simply with suppression of the immune response.

Hepatitis C and mild or moderate cryoglobulinemia are usually treated with standard hepatitis C treatments. Cryoglobulinemia may return back with the discontinuation of the treatment.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used in patients with arthralgia and fatigue.

Immunosuppressive medications (eg, corticosteroid therapy and/or cyclophosphamide or azathioprine) are indicated upon evidence of organ involvement such as vasculitis, renal disease, progressive neurologic findings, or disabling skin manifestations.

Erythematous and purpuric vasculitic lesions on the lower leg, a classic cutaneous manifestation associated with cryoglobulinemia.

Plasmapheresis is indicated for severe or life-threatening complications related to in vivo cryoprecipitation or serum hyperviscosity. Concomitant use of high-dose corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents is recommended for reduction of immunoglobulin production.

Rituximab therapy has been used predominantly in HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemia refractory to or unsuitable for corticosteroids and antiviral (IFN-alfa) therapy. Rituximab therapy is reportedly well tolerated in this patient population; however, treatment has resulted in increased titers of HCV RNA of undetermined significance.

Summary:

Cryoglobulinemia is a cold-sensitive immunoglobulin disorder in which monoclonal or mixed cryoglobulins precipitate at low temperatures and trigger immune-complex vasculitis affecting the skin, kidneys, nerves, and peripheral circulation. The condition is most frequently associated with chronic hepatitis C infection, autoimmune diseases, and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Clinically, patients present with palpable purpura, Raynaud’s phenomenon, arthralgia, fatigue, neuropathy, or features of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Diagnosis relies on careful temperature-controlled cryoglobulin testing, cryocrit quantification, complement levels, and targeted evaluation of underlying causes. Management is directed at the trigger—typically antiviral therapy for HCV, immunosuppression for autoimmune disease, and rituximab for mixed cryoglobulinemia or systemic vasculitis—with plasmapheresis reserved for severe or rapidly progressive manifestations. Early recognition and targeted therapy significantly improve outcomes.

Questions and Answers:

What are the most common symptoms of cryoglobulinemia?

Symptoms typically include palpable purpura, vasculitis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fatigue, arthralgia, neuropathy, and signs of renal involvement such as proteinuria or hematuria. Skin lesions and cold sensitivity are particularly characteristic.

How is cryoglobulinemia diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves detecting cryoglobulins in serum using temperature-controlled sample handling, assessing cryocrit, checking complement levels (often low C4), and evaluating associated conditions such as hepatitis C, autoimmune disease, or lymphoproliferative disorders. Renal or skin biopsy may confirm immune-complex vasculitis.

What conditions are most commonly associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia?

Mixed cryoglobulinemia is most frequently linked to chronic hepatitis C infection, autoimmune diseases (especially Sjögren’s syndrome and SLE), and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.

What do cryoglobulins look like in the laboratory?

Cryoglobulins typically appear as a white or cloudy precipitate when serum is cooled to 4°C and dissolve completely when warmed to 37°C. This reversible precipitation is diagnostic and reflects the thermolabile nature of immunoglobulins.

Can cryoglobulinemia cause kidney damage?

Yes. Cryoglobulinemia can cause membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis due to immune-complex deposition, leading to proteinuria, hematuria, reduced kidney function, and in severe cases, progressive renal failure.

Is Raynaud’s phenomenon related to cryoglobulinemia?

Raynaud’s can occur in cryoglobulinemia due to cold-induced immune-complex precipitation and vascular obstruction. It commonly presents with triphasic color changes of the fingers triggered by cold exposure.

How is cryoglobulinemia-related vasculitis treated?

Management depends on severity and underlying cause. Treatment may include antivirals for hepatitis C, corticosteroids, rituximab for immune-mediated disease, and plasmapheresis for severe or life-threatening vasculitic complications.

What is the difference between cryoglobulinemia and cold agglutinin disease?

Cryoglobulinemia involves immune-complex precipitation of immunoglobulins, while cold agglutinin disease involves IgM-mediated red blood cell agglutination at low temperatures. The mechanisms, symptoms, and laboratory findings differ significantly.

When should patients with cryoglobulinemia be referred to a specialist?

Referral to a hematologist or rheumatologist is recommended when patients have vasculitis, renal involvement, neuropathy, or systemic symptoms, or when mixed cryoglobulinemia is suspected in the context of hepatitis C or autoimmune disease.

References:

Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, Bosch X. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet. 2011;378(9803):348-360.

Adam M Tritsch, MD. Cryoglobulinemia: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology. Medscape. Accessed June 2016.

Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins: A report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57(5):775-788.

Ferri C, Zignego AL, Pileri SA. Cryoglobulins. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(1):4-13.

Iannuzzella F, Vaglio A, Garini G. Management of hepatitis C virus–related mixed cryoglobulinemia. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):400-408.

Sansonno D, De Re V, Lauletta G, Tucci FA, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment of mixed cryoglobulinemia resistant to interferon-alpha. Blood. 2003;101(10):3818-3826.

Pramod Kerkar, MD. Cryoglobulinaemia: Epidemiology, Causes, Treatment, Investigations. EPainAssist. Accessed June 2015.

De Vita S, Quartuccio L, Isola M, et al. Rituximab for severe cryoglobulinemic vasculitis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):843-853.

Herrick AL. Pathogenesis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatology. 2012;51(3):1157-1166.

Zignego AL, Ferrari F, Ferri C. Hepatitis C virus infection and cryoglobulinemia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(Suppl 124):92-101.

Bonacci M, Vitale A, Quartuccio L, et al. Mixed cryoglobulinemia: New insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2018;18(3):363-371.

Ferri C, Sebastiani M, Giuggioli D, et al. Mixed cryoglobulinemia: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 231 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(2):87–108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15028958/

Zignego AL, Ferrari F, Monti M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and mixed cryoglobulinemia: A paradigm of systemic autoimmune disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:945948. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9387570/

Keywords:

cryoglobulinemia, cryoglobulinaemia, cryoglobulinemia symptoms, cryoglobulinemia vasculitis, cryoglobulinaemia rash, cryoglobulinaemia diagnosis, cryoglobulinaemia causes, cryoglobulinaemia pictures, cryoglobulinaemia treatment, cryoglobulinaemia types, mixed cryoglobulinaemia, mixed cryoglobulinemia symptoms, cryoglobulinemia hepatitis C, hepatitis C mixed cryoglobulinemia, cryoglobulinemia renal disease, cryoglobulinemia glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemia neuropathy, cryoglobulinemia skin lesions, cryoglobulinemia purpura, cryoglobulin testing, how to test for cryoglobulinemia, cryocrit test, cryoprecipitate formation, cold-induced vasculitis, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, immune-complex vasculitis, cryoglobulin, temperature-dependent immunoglobulin precipitation, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Raynaud’s disease, Raynaud’s cryoglobulinemia, cryoglobulinemia management, cryoglobulinemia rituximab treatment, cryoglobulinemia autoimmune disease, cryoglobulinemia lymphoproliferative disorders

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

If I have tested negative for lupus and RA antibodies on labs, is it possible to still have type I? I was unclear as to whether all three types are dependent upon the same rheumatoid immunoglobulins I would have been tested for by my rheumatologist (cardiolipin ab, IGG, IGM, IGA). All results were negative, non fasting, however these and other symptoms persist. I am hoping to determine what doctor to see next. Your website is extremely helpful in this. Thank you in advance!

Hi Heather,

Thanks for your comment.

You haven’t mentioned the clinical presentation in your case and what was your main presenting symptom?

Type I cryoglobulinemia is most commonly encountered in patients with a plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Have you had your serum immunoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis, serum free light chains, and BJP in the urine checked?

Hello again, and thank you for the reply. A neurologist referred me to a rheumatologist based on what he felt was lupus symptoms – raynauds, a rash, brain fog, pain, abdominal discomfort. He also referred me to a hematologist for bleeding (mainly gums), and also tiny under the skin red spots that break open and bleed (separate from the rash, which is red, raised, and itchy). Then, he referred me to a pain management doctor for my primary complaint of bone pain, mainly my spine, that left my feet numb and tingly as well as my hands. Hands go numb while using them and in the morning, feet are discolored purple and tingly most of the time. The back pain is severe, making it difficult to sleep, and has begun causing shoulder and leg pain as well as an expanding pressure type headache at the base of my skull that wraps towards my ear, ending behind my right eye.

Everything seems to begin with my spine, or rather can be traced back to it. I am 36 with low vitamin D (13L), spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, calcified discs… however the only lab work that has been done was the CBC, and the lupus screening -bloodwork only, no urine. She ran sm /rnp antibody, C-reactive protein, cardiolipin ab (iga, igg, igm). Due to the bone pain and degree of stenosis/degeneration on my spine for my age, plus the CNS symptoms, my concern was myeloma of the spine. Naturally, with how rare it is, I was not sure if it was included in the panels she ran or would even show up as an abnormality in a CBC. The discoloration on my feet looks very similar to the cryoglobunemia pictures included in your article.

Hi Heather,

Thanks for your comment and for sharing your experience with us.

If you are concerened about myeloma, in addition to the investigations I suggested in my previous reply, you can ask your GP or your local Hematologist to arrange an MRI scan spine or better a whole-body FDG PET CT scan to screen your whole body.

BW,