Hemolytic Anemias

Introduction:

Red blood cells (RBCs) are produced in the bone marrow and normally survive in the circulation for approximately 120 days before being removed by the reticuloendothelial system. Hemolysis refers to the premature destruction of red blood cells, resulting in a shortened RBC lifespan of less than 120 days. In response, the bone marrow increases erythropoiesis to compensate for the accelerated RBC loss. However, in hemolytic anemias, this compensatory response is often insufficient to meet the body’s oxygen-carrying demands. Anemia develops when bone marrow production can no longer adequately offset the reduced RBC survival, a state known as uncompensated hemolytic anemia. When erythropoietic activity successfully maintains near-normal hemoglobin levels despite ongoing hemolysis, the condition is termed compensated hemolytic anemia.

Clinical features:

Patients with hemolytic anemia typically present with symptoms of anemia, including fatigue, generalized weakness, reduced exercise tolerance, and exertional shortness of breath. Mild jaundice is common due to elevated unconjugated bilirubin from increased red cell destruction. Splenomegaly may be present to varying degrees, reflecting heightened clearance of damaged red cells. In chronic hemolysis, patients may develop leg ulcers, particularly around the ankles, and may experience biliary colic resulting from pigment gallstones, a known complication of long-standing unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

A chronic leg ulcer near the ankle in a patient with sickle cell anaemia, caused by recurrent vaso-occlusion, chronic hemolysis, impaired tissue perfusion, and local ischemia. Such ulcers are typically painful, slow to heal, and reflect long-standing disease severity.

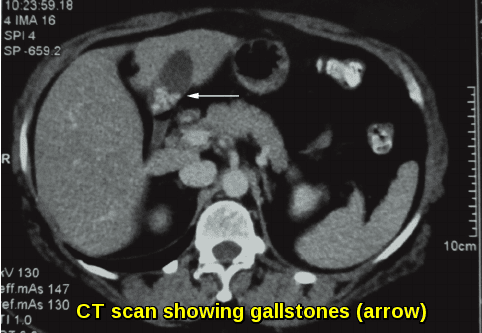

Abdominal CT scan demonstrating pigment gallstones (arrow) in a patient with chronic hemolytic anemia, formed as a result of long-standing unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia secondary to accelerated red blood cell destruction.

Aetiology:

The causes of hemolysis are broad and diverse, ranging from inherited defects of the red cell membrane, enzymes, or hemoglobin to a wide spectrum of acquired disorders. Numerous diseases, medications, infections, and immune-mediated processes can accelerate the destruction of red blood cells. While most cases can be attributed to identifiable inherited or acquired mechanisms, some patients present with hemolytic anemia in whom no clear etiology is found, despite comprehensive evaluation.

Inherited Hemolytic Anemias:

In inherited hemolytic anemias, genetic abnormalities disrupt normal red blood cell production and function. These faulty genes give rise to structurally or biochemically abnormal red cells, and the specific defect determines the subtype of hemolytic disorder.

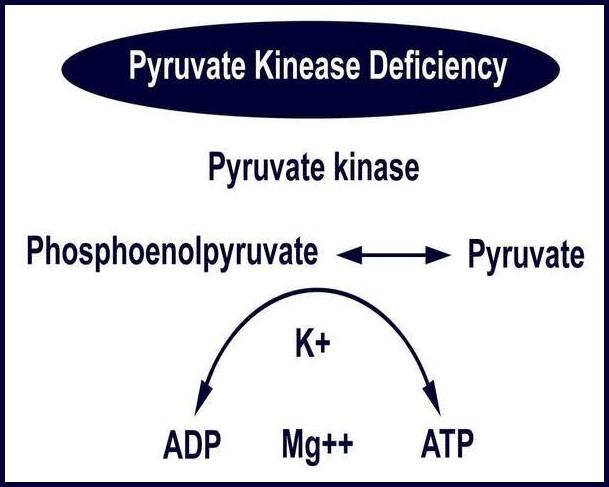

The underlying abnormality may involve the hemoglobin molecule (as in sickle cell disease or thalassemia), the red cell membrane (such as hereditary spherocytosis or elliptocytosis), or key metabolic enzymes required to maintain RBC integrity (e.g., G6PD or pyruvate kinase deficiency).

These genetically altered red blood cells are often fragile and prone to premature destruction, either within the circulation or during passage through the spleen, where damaged or misshapen cells are selectively removed by the reticuloendothelial system.

Acquired Hemolytic Anemias:

In acquired hemolytic anemias, red blood cells are produced normally by the bone marrow, but are subsequently destroyed prematurely due to an external pathological process. A wide range of diseases, immune mechanisms, infections, drugs, and systemic conditions can trigger accelerated red cell destruction.

Examples of conditions associated with acquired hemolysis include:

- Immune disorders e.g. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Infections which may be viral or bacterial e.g. Epstein–Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Hepatitis viruses, HIV.

- Malignancy e.g. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and other hematological cancers.

- Reactions to medications or blood transfusions. Drugs that can cause immune hemolytic anemia include: Cephalosporins, Dapsone, Levodopa, Levofloxacin, Methyldopa, Nitrofurantoin, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), Penicillin and its derivatives, Quinidine.

- Hypersplenism, where excessive splenic sequestration leads to increased red cell destruction.

A thorough clinical history, focused physical examination, and detailed review of the peripheral blood film often provide crucial early clues to the underlying cause of hemolysis. These initial steps help distinguish immune from non-immune mechanisms and guide further targeted investigations.

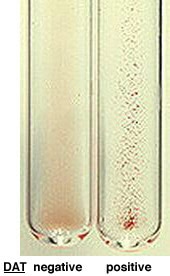

The Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT), also known as the Direct Coombs Test (DCT), is the essential next investigation. It detects antibody or complement bound to the red blood cell surface, thereby confirming immune-mediated hemolysis when positive.

In cases of DAT-negative hemolysis, where no clear etiology is evident from the history, examination, or blood film, a systematic and empirical diagnostic approach is required. Common and clinically significant conditions—such as G6PD deficiency and other enzyme or membrane defects—should be considered early to avoid diagnostic delays.

Investigations:

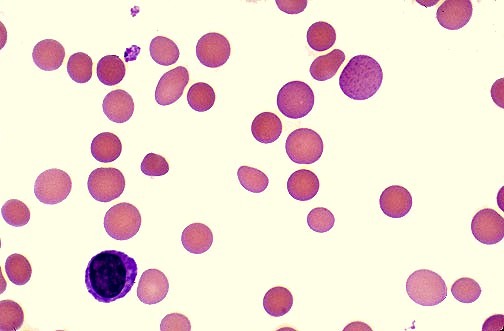

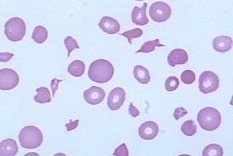

Peripheral blood smear: may show abnormal red cells, e.g. sickle cells, spherocytes, schistocytes, irregularly contracted cells, and nucleated red blood cells (NRBCs).

Peripheral blood film showing spherocytes, a hallmark feature of warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). These small, dense red cells lacking central pallor result from antibody-mediated red cell membrane loss and are a key diagnostic clue in immune-mediated hemolysis.

Peripheral blood film showing numerous schistocytes, fragmented red blood cells characteristic of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA). These irregularly shaped RBC fragments arise from mechanical destruction within the circulation and are seen in conditions such as DIC, TTP, HUS, malignant hypertension, and mechanical heart valves.

Reduced hemoglobin (Hb).

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) may be normal or raised, particularly in reticulocytosis.

Reticulocytosis, reflecting increased bone marrow response to hemolysis.

Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT), detects antibody or complement bound to the red blood cell surface, thereby confirming immune-mediated hemolysis when positive.

Comparison of Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) results showing a negative tube with no agglutination and a positive DAT demonstrating visible red cell clumping. A positive DAT confirms immune-mediated hemolysis, as seen in warm or cold autoimmune hemolytic anemia, transfusion reactions, and drug-induced hemolysis.

Raised serum free hemoglobin, particularly in intravascular hemolysis.

Hemoglobinuria (intravascular hemolysis) and hemosiderinuria in chronic cases.

Raised unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin, due to increased heme breakdown.

Raised serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a sensitive marker of hemolysis.

Low serum haptoglobin, especially in intravascular hemolysis.

Low serum folate may be present due to increased erythropoietic demand.

Serum Mycoplasma pneumoniae and EBV antibodies (IgM & IgG) when infection-related hemolysis is suspected.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis for the diagnosis of hemoglobinopathies.

Chest X-ray (CXR) when clinically indicated.

Abdominal ultrasound scan (USS) to assess splenomegaly and detect pigment gallstones.

Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA)

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a relatively uncommon but clinically significant disorder caused by autoantibodies directed against the patient’s own red blood cells, resulting in immune-mediated hemolysis. AIHA may be idiopathic or secondary to autoimmune diseases, lymphoproliferative disorders, infections, or bone marrow transplantation.

It is classified according to the thermal activity of the autoantibody into warm AIHA, cold AIHA—including cold hemagglutinin disease (CHAD) and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria—or mixed AIHA. The condition may develop gradually with mild symptoms or present abruptly with a fulminant and life-threatening anemia characterized by rapid red cell destruction. The clinical features, etiological factors, and baseline investigations mirror those described for other hemolytic anemias, with a positive Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) serving as a key diagnostic criterion in immune-mediated cases.

The first-line treatment for warm AIHA is corticosteroid therapy, effective in approximately 70–85% of patients. Prednisone is typically initiated at 1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day for 1–3 weeks until hemoglobin rises above 10 g/dL; most patients respond during the second week, and lack of improvement by the third week suggests steroid resistance. Once hemoglobin stabilizes, prednisone should be tapered gradually, reducing the dose by 10–15 mg weekly to 20–30 mg/day, then by 5 mg every 1–2 weeks to 15 mg/day, and subsequently by 2.5 mg every two weeks with the goal of complete withdrawal. Despite the temptation to taper more rapidly, patients should remain on low-dose prednisone (≤10 mg/day) for at least 3–4 months to reduce relapse risk.

For refractory or relapsed disease, Rituximab—a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody targeting B-cells—has demonstrated high efficacy in both warm AIHA and CHAD, with a typical regimen of 375 mg/m² weekly for four weeks. Rituximab is effective in idiopathic and secondary AIHA, including those associated with autoimmune conditions, lymphoproliferative disorders, and post-transplantation. In CHAD, Rituximab is now recommended as first-line therapy. Splenectomy remains an established third-line option for warm AIHA, particularly in patients who do not respond to corticosteroids or Rituximab, those requiring long-term prednisone doses above 10 mg/day, or patients experiencing multiple relapses.

Patients who remain refractory despite these measures may benefit from additional immunosuppressive therapies such as azathioprine (Imuran), cyclophosphamide, cyclosporin, or mycophenolate mofetil. Other adjunctive or rescue treatments include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), danazol, plasma exchange, and, in the most resistant cases, alemtuzumab.

Questions and Answers:

What is hemolytic anemia?

Hemolytic anemia is a condition in which red blood cells are destroyed prematurely at a rate that exceeds the bone marrow’s capacity to replace them, leading to reduced red cell survival and anemia.

What are the main causes of hemolytic anemia?

Hemolytic anemia may be inherited due to genetic defects affecting hemoglobin, red cell membranes, or enzymes, or acquired as a result of autoimmune disease, infections, malignancy, drugs, transfusion reactions, or hypersplenism.

What causes jaundice in hemolytic anemia?

Jaundice in hemolytic anemia is caused by increased breakdown of hemoglobin leading to elevated unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin in the blood.

Why does splenomegaly occur in hemolytic anemia?

Splenomegaly occurs due to increased sequestration and destruction of abnormal red blood cells within the spleen during chronic hemolysis.

What are the typical blood film findings in hemolytic anemia?

Peripheral blood film may show spherocytes in autoimmune hemolytic anemia, schistocytes in microangiopathic hemolysis, sickle cells in sickle cell disease, nucleated red blood cells, and other abnormal red cell forms.

What does a positive Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT) indicate?

A positive DAT confirms immune-mediated hemolysis by detecting antibodies or complement bound to the red blood cell surface, as seen in autoimmune hemolytic anemia and transfusion reactions.

What causes pigment gallstones in hemolytic anemia?

Chronic hemolysis leads to persistent elevation of unconjugated bilirubin, which precipitates as pigment gallstones within the gallbladder.

What is warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia?

Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is caused by IgG autoantibodies that react optimally at body temperature, leading to splenic red cell destruction and DAT positivity.

What is cold agglutinin disease (CHAD)?

Cold agglutinin disease is a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia mediated by IgM antibodies that bind red blood cells at low temperatures and activate complement.

What is the first-line treatment for warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia?

Corticosteroids, usually prednisone at 1–1.5 mg/kg/day, are the first-line treatment and achieve remission in most patients.

When is rituximab used in autoimmune hemolytic anemia?

Rituximab is used in steroid-refractory or relapsed autoimmune hemolytic anemia and is now considered first-line therapy for cold agglutinin disease.

What is the role of splenectomy in autoimmune hemolytic anemia?

Splenectomy is a third-line treatment for warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients who fail corticosteroids and rituximab or require long-term high-dose prednisone.

Why does reticulocytosis occur in hemolytic anemia?

Reticulocytosis reflects increased bone marrow response to accelerated red blood cell destruction.

What laboratory tests confirm intravascular hemolysis?

Intravascular hemolysis is confirmed by elevated free serum hemoglobin, hemoglobinuria, hemosiderinuria, low haptoglobin, and raised LDH.

Why do patients with sickle cell disease develop leg ulcers?

Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease result from chronic hemolysis, repeated vaso-occlusion, ischemia, poor tissue oxygenation, and local inflammation.

What causes schistocytes on the blood film?

Schistocytes arise from mechanical red cell fragmentation in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia such as DIC, TTP, HUS, malignant hypertension, and prosthetic heart valves.

What does a DAT-negative hemolytic anemia suggest?

DAT-negative hemolysis suggests non-immune causes such as enzyme deficiencies (e.g. G6PD), membrane disorders, mechanical hemolysis, or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

References:

Gehrs BC, Friedberg RC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:258–271.

Hoffman PC. Immune hemolytic anemia – selected topics. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:13–18.

Arndt PA, Garratty G. The changing spectrum of drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:137–144.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). What Causes Hemolytic Anemia? Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ha/causes

Michel M. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Orphanet. August 2010. Available at: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=13392

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Types of Hemolytic Anemia. March 21, 2014. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ha/types.html

Keywords:

hemolytic anemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, warm AIHA, cold agglutinin disease, CHAD, paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria, DAT positive hemolysis, direct antiglobulin test, Coombs test, spherocytes blood film, schistocytes microangiopathic hemolysis, red cell destruction, intravascular hemolysis, extravascular hemolysis, jaundice in hemolysis, splenomegaly hemolytic anemia, pigment gallstones hemolysis, sickle cell leg ulcer, hemolytic anemia investigations, raised LDH hemolysis, low haptoglobin hemolysis, reticulocytosis, indirect bilirubin raised, hereditary hemolytic anemia, acquired hemolytic anemia, drug-induced hemolysis, G6PD deficiency hemolysis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemolysis, EBV hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, hemosiderinuria, blood film abnormalities, corticosteroids AIHA treatment, rituximab AIHA, splenectomy AIHA, immunosuppressive therapy hemolysis, IVIG hemolysis, plasma exchange hemolysis, alemtuzumab refractory AIHA, spherocytes warm AIHA image, schistocytes MAHA image, DAT positive negative image, CT scan pigment gallstones hemolysis

That is fantastic and good meaningfull information for me, wish you to prepared good hematology series lactures. Proud you for next and new knowledge.