Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

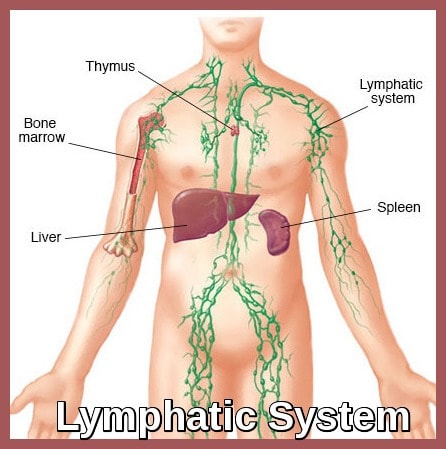

Lymphatic system diagram illustrating key lymphoid organs involved in the development and spread of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) represents a broad and biologically diverse group of lymphoid malignancies arising from the clonal proliferation of B-cells, T-cells, or, less commonly, natural killer (NK) cells. The majority of non-Hodgkin lymphomas are of B-cell origin, while a smaller subset arises from T-cell or natural killer (NK) cell lineages. These cancers originate within the lymphatic system and may involve lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, liver, or extranodal sites such as the gastrointestinal tract.

The development of NHL is driven by a combination of genetic and molecular abnormalities—most notably chromosomal translocations and dysregulated signalling pathways—together with recognised risk factors including Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), immunodeficiency, autoimmune disorders, certain environmental exposures, and chronic antigenic stimulation.

Given the considerable heterogeneity of NHL subtypes, each with distinct clinical behaviour, morphology, and therapeutic responsiveness, accurate classification and timely diagnosis are crucial for optimising management strategies and improving survival outcomes.

Clinical features:

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma occurs mainly in the elderly, although some cases occur in childhood.

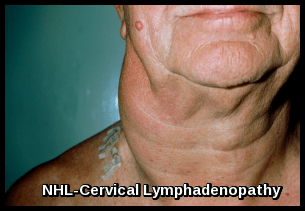

Most patients have widespread painless and slowly progressive lymphadenopathy at presentation (cf: Hodgkin’s Disease).

Cervical lymphadenopathy caused by non-Hodgkin lymphoma, demonstrating characteristic unilateral neck swelling.

Hepatosplenomegaly is common.

Patients with less aggressive disease often have no symptoms, whereas those with aggressive disease tend to have B symptoms ((unexplained weight loss >10% of total body weight within the past 6 months, unexplained fever >38º C, or drenching night sweats).

Extranodal involvement: More than one-third of patients; most common sites are GI/GU tracts (including Waldeyer ring), skin, bone marrow, sinuses, thyroid, CNS.

Bone marrow involvement: May be associated with cytopenias and fatigue/weakness. More common in advanced-stage disease.

Two problems are common in NHL but rare in Hodgkin lymphoma: Congestion and oedema of the face and neck from pressure on the superior vena cava (superior vena cava or superior mediastinal syndrome) may occur. Also, ureters may be compressed by retroperitoneal or pelvic lymph nodes or both; this compression may interfere with urinary flow and cause secondary renal failure.

Clinical examination:

Examination in patients with low-grade lymphomas may demonstrate peripheral adenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.

Intermediate- and high-grade lymphomas may result in the following examination findings:

- Rapidly growing and bulky lymphadenopathy

- Splenomegaly

- Hepatomegaly

- Large abdominal mass: Usually in Burkitt lymphoma

- Testicular mass

- Skin lesions: Associated with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and angioimmunoblastic lymphoma

Investigations:

FBC, blood film, and DCT:

Anemia is not infrequent. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia may occur especially in low-grade lymphoma.

Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occur if there is marrow failure, hypersplenism or an immune destruction.

Malignant cells are not usually detectable in the blood although a leukemic element may develop in the later stages.

Biochemistry & Immunology:

May show elevated LDH, calcium and uric acid levels, abnormal liver function tests. Serum beta2-microglobulin level may be elevated.

Hypoalbuminemia and hypergammaglobulinemia and M bands are not infrequent, though the M band level is usually small or moderate.

Viral serology:

- HIV serology: Especially in patients with diffuse large cell immunoblastic or small noncleaved histologies.

- Human T-cell lymphotropic virus-1 serology: For patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma.

- Hepatitis B testing: In patients in whom rituximab therapy is planned because reactivation has been reported.

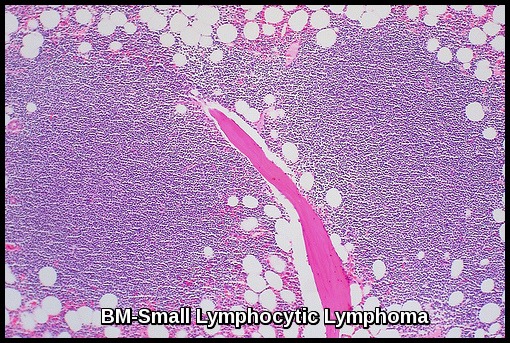

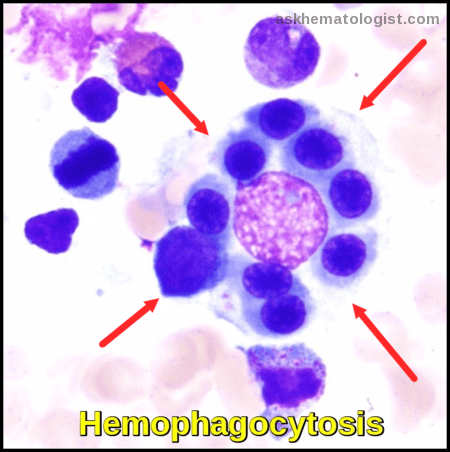

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy:

Bone marrow section demonstrating small lymphocytic lymphoma, a low-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterised by diffuse lymphoid infiltration.

Excisional lymph node biopsy:

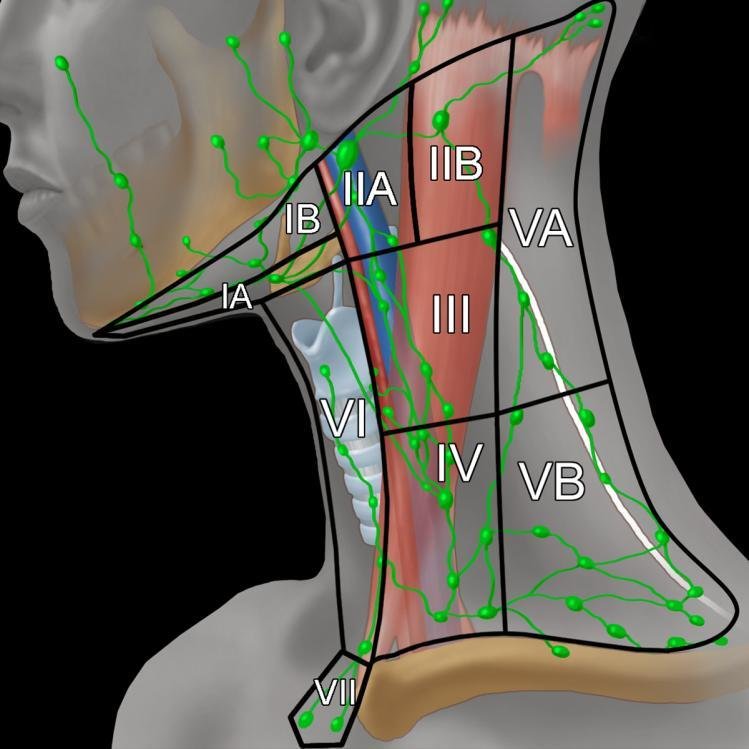

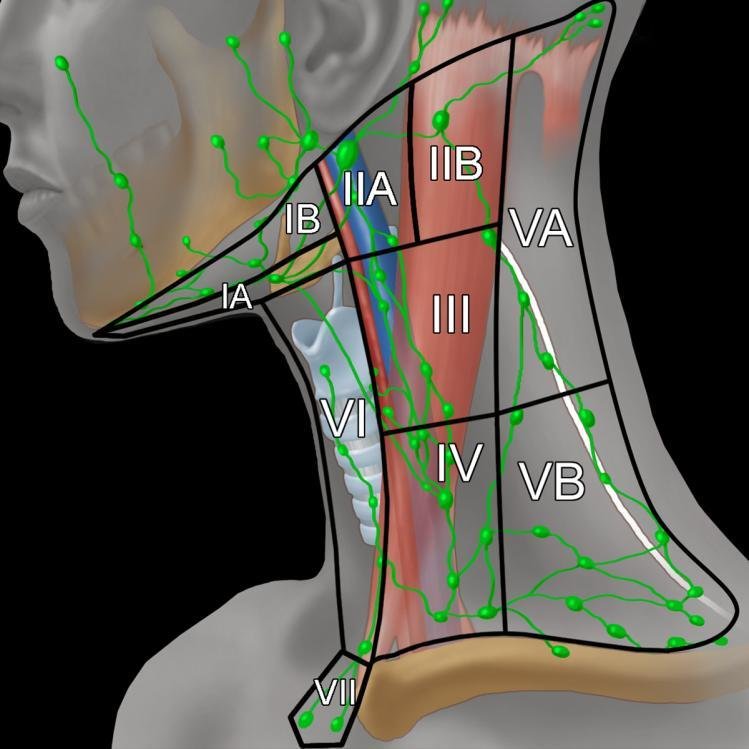

Illustration of the cervical lymph node levels and their anatomical boundaries, demonstrating key regions assessed in neck dissections and staging of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Adapted from Imaging Anatomy: Brain, Head and Neck, Spine, “Cervical Lymph Nodes,” Gordon H and Harnsberger HR, 2006, Amirsys/Elsevier, p. 253. Reproduced with permission.

A lymph node biopsy is done if lymphadenopathy is confirmed on chest x-ray, CT, or PET. If only mediastinal nodes are enlarged, patients require CT-guided needle biopsy or mediastinoscopy.

Histologic criteria on biopsy include destruction of normal lymph node architecture and invasion of the capsule and adjacent fat by characteristic neoplastic cells.

Lymph node biopsy demonstrating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a high-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterised by diffuse sheets of large atypical lymphoid cells.

Immunophenotypic studies help to distinguish reactive from neoplastic lymphoid infiltrates, and lymphoid from nonlymphoid malignancies. They are of great value in identifying specific lymphoid subtypes and helping define prognosis and management; these studies also can be done on peripheral cells and bone marrow. Demonstration of the leucocyte common antigen CD45 by immunoperoxidase rules out metastatic cancer, which is often in the differential diagnosis of “undifferentiated” cancers.

Breast tissue infiltrated by CD5-positive chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), illustrating extranodal involvement in indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

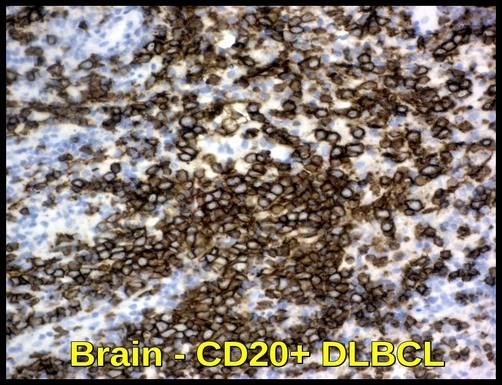

Brain tissue infiltrated by CD20-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), demonstrating CNS involvement by an aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The test for leucocyte common antigen, most surface marker studies, and gene rearrangement (to document B-cell or T-cell clonality) can be done on fixed tissues.

Cytogenetics and flow cytometry require fresh tissue.

All follicular lymphomas are of B-cell origin as are the majority of the diffuse NHL. T-cell NHL accounts for 10-15% of the diffuse NHL.

Immunophenotypic profiles of common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes, highlighting characteristic expression patterns of CD5, CD19, CD20, CD23, and additional diagnostic markers.

Although bcl -2 expression distinguishes follicular lymphoma from reactive follicular hyperplasia, bcl -1 expression strongly favors a diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a subtype of B-cell lymphomas which overexpress cyclin D1 due to a t(11:14) chromosomal translocation in the DNA.

CD30 expression is important for the recognition of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and it can also be found in the majority of Hodgkin lymphomas.

Cytogenetic studies:

Cytogenetic abnormalities have been identified in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and significant correlations among them and morphology, immunophenotyping, and parameters of clinical outcome have been recognized.

Various technological advances in cytogenetics combined with molecular approaches have greatly enhanced the ability to identify genetic abnormalities in any given tumor type.

Most follicular lymphomas have a t(14;18) translocation which results in high-level expression of the bcl-2 gene with protection of such cells from apoptosis.

Translocation t(11;14) is detected in 65% of mantle cell lymphoma cases by classic cytogenetic analysis, and in nearly all cases, by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

Rearrangements of the bcl-6 gene are common in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and t(8;14) translocations are frequent in small non-cleaved cell lymphomas e.g. Burkitt’s lymphoma, resulting in high-level expression of the proto-oncogene c-myc.

Lumbar puncture for CSF analysis:

lumbar puncture for CSF analysis is indicated in patients with the following conditions:

- Diffuse aggressive NHL with bone marrow, epidural, testicular, paranasal sinus, or nasopharyngeal involvement, or 2 or more extranodal sites of disease.

- High-grade lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- High-grade small non-cleaved cell lymphomas e.g. Burkitt lymphoma.

- HIV-related lymphoma.

- Primary CNS lymphoma.

- Neurologic signs and symptoms.

Imaging studies:

The following imaging studies should be obtained in a patient suspected of having Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma:

- Chest radiography.

- Echocardiogram & ECG: For patients being considered for treatment with anthracyclines.

- CT scanning of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

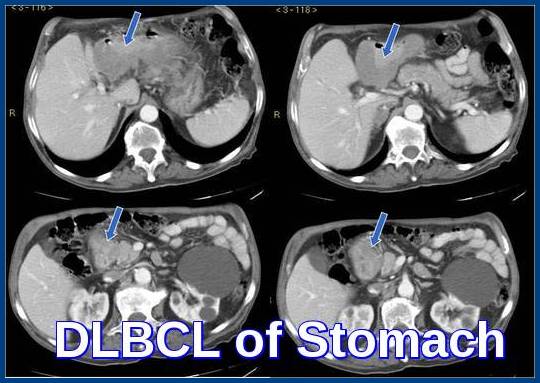

Axial CT images demonstrating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the stomach, with prominent gastric wall thickening and perigastric involvement characteristic of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

- PET-CT scan: For baseline/staging in Aggressive NHL Including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

- Testicular ultrasonography: For opposite testis in male patients with a testicular primary lesion.

- MRI of brain/spinal cord: For suspected primary CNS lymphoma, lymphomatous meningitis, paraspinal lymphoma, or vertebral body involvement by lymphoma.

- Bone scanning: Only in patients with bone pain, elevated alkaline phosphatase, or both.

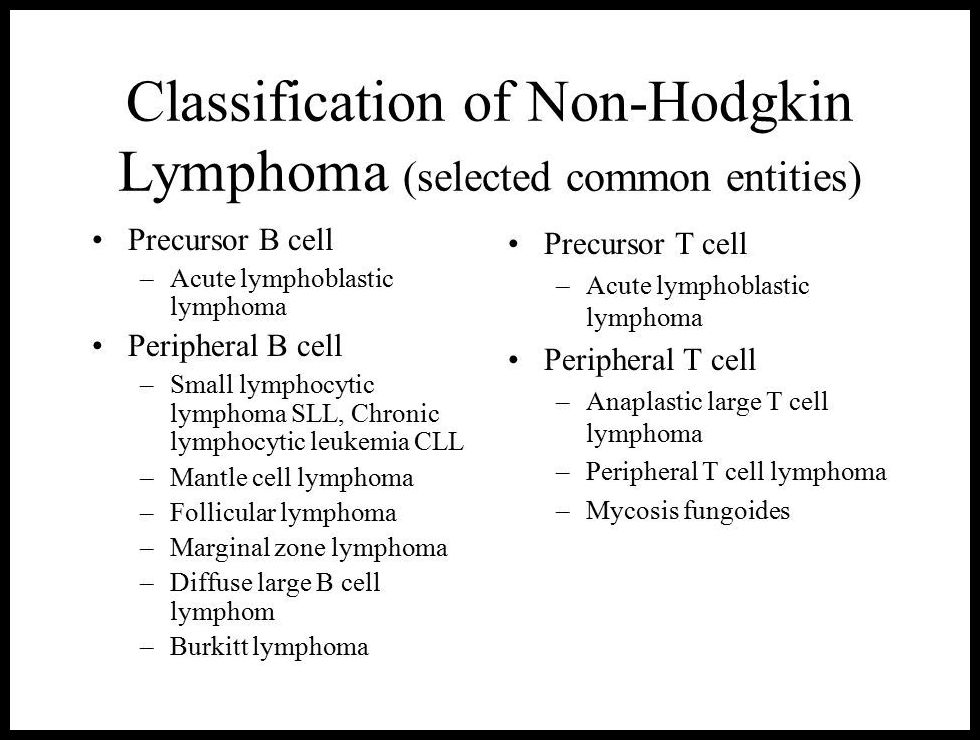

Classification:

- Many histological classifications are available illustrating their difficulty and deficiencies.

- The classification used below (working formulation) is based on whether or not the tumor is diffuse or follicular, whether the cells are small or large and whether or not the nuclei are regular, cleaved or convoluted.

- Reactive elements are in general less pronounced than in Hodgkin’s Disease.

- This classification does not take immunophenotype into account, although such studies do add additional information. One of the other weaknesses of this classification is that it does not take account of biological entities such as tumors of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).

- The WHO classification is valuable because it incorporates immunophenotype, genotype, and cytogenetics, but numerous other systems exist.

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas are commonly also categorized as indolent or aggressive. Indolent lymphomas are slowly progressive and responsive to therapy but are not curable with standard approaches. Aggressive lymphomas are rapidly progressive but responsive to therapy and often curable.

- In children, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma is almost always aggressive. Follicular and other indolent lymphomas are very rare. The treatment of these aggressive lymphomas (Burkitt, diffuse large B cell, and lymphoblastic lymphoma) presents special concerns, including GI tract involvement (particularly in the terminal ileum); meningeal spread (requiring CSF prophylaxis or treatment); and other sites of involvement (eg, testes, brain). In addition, with these potentially curable lymphomas, treatment adverse effects as well as outcome must be considered, including late risks of secondary cancer, cardiorespiratory sequelae, fertility preservation, and developmental consequences. Current research is focused on these areas as well as on the molecular events and predictors of lymphoma in children.

Germinal Centre B-Cell (GCB) and Activated B-Cell (ABC) Subtypes:

In B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, particularly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), molecular and immunophenotypic characterisation divides cases into major subtypes according to their cell of origin: the germinal centre B-cell (GCB) type, the activated B-cell (ABC) type, and the non-GCB type. The GCB subtype arises from B cells within the germinal centre and expresses CD10, BCL6, and LMO2, typically demonstrating a favourable prognosis and good response to the R-CHOP regimen.

The ABC subtype (also called post-germinal-centre or plasmablastic type) originates from activated peripheral B cells, characterised by MUM1/IRF4, XBP1, and BCL2 expression, with constitutive NF-κB pathway activation leading to a poorer clinical outcome. Patients with ABC or non-GCB phenotypes—which lack germinal-centre markers (CD10-, variable BCL6, MUM1+) and share molecular similarities—often show reduced responsiveness to standard immunochemotherapy. These subtypes may benefit from novel targeted therapies, including BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib), lenalidomide, and the recently approved Pola-R-CHP regimen (polatuzumab vedotin combined with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone), which has demonstrated improved progression-free survival compared with R-CHOP in newly diagnosed DLBCL, particularly in non-GCB and high-risk patients.

Accurate subclassification using immunohistochemistry or gene-expression profiling is therefore essential for optimal risk stratification, therapeutic selection, and prognostic assessment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

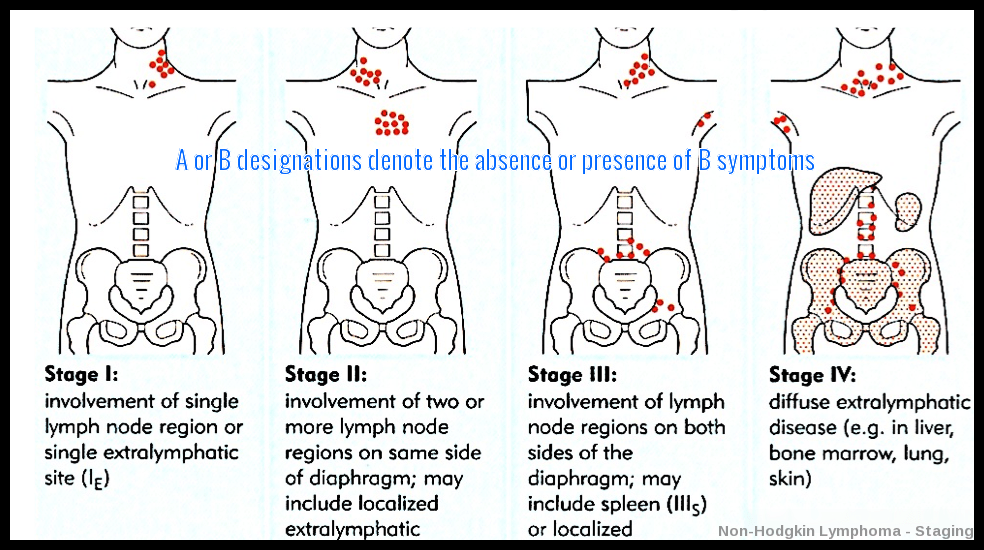

Staging:

- Although localized Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma does occur, the disease is typically disseminated when first recognized.

- Staging procedures include CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; PET; and bone marrow biopsy.

The final staging of NHL is similar to that of Hodgkin lymphoma and is based on clinical and pathologic findings.

Illustration of the Ann Arbor staging system for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, depicting progressive involvement from a single nodal region (Stage I) to diffuse extranodal disease (Stage IV), with A/B suffixes indicating absence or presence of B symptoms.

Treatment:

Low-grade lymphomas although incurable at present, often progress very slowly, and treatment should only be given to relieve symptoms, or in a clinical trial.

In the intermediate and high-grade lymphomas patients are nearly all symptomatic and more aggressive therapy is justified as there is a chance of cure.

For the initial treatment of patients with high-grade lymphoma and patients with bulky disease, an inpatient setting is recommended in order to monitor for tumor lysis syndrome and to manage appropriately.

Localized disease (stages I and II):

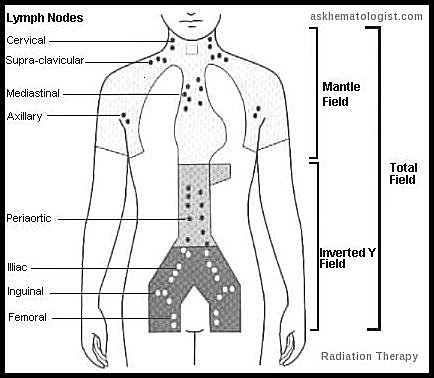

Patients with indolent lymphomas rarely present with localized disease, but when they do, regional Radiation Therapy (RT) may offer long-term control. However, relapses may occur > 10 years after radiation therapy.

About half of patients with aggressive lymphomas present with localized disease, for which combination chemotherapy, with or without regional radiation, is usually curative.

Patients with lymphoblastic lymphomas or Burkitt lymphoma, even if apparently localized, must receive intensive combination chemotherapy with meningeal prophylaxis. Treatment may require maintenance chemotherapy, but cure is expected.

Advanced disease (stages III and IV):

For indolent lymphomas, treatment varies considerably. Follicular lymphoma comprises 70% of this group. Other entities in this group include small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphomas (MZL). A watch-and-wait approach or treatment with the B-cell specific monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab alone or combined with chemotherapy may be used. Criteria considered in selecting management options include age, general health, distribution of disease, tumor bulk, histology, and anticipated benefits of therapy. Single-agent treatment with chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide (with or without prednisone) is useful in elderly patients with significant comorbidities. However, only a few achieve remission; most achieve palliation.

Bendamustine plus rituximab has demonstrated efficacy for the first-line treatment of advanced follicular, indolent, and mantle cell lymphomas.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines give bendamustine plus rituximab, R-CHOP, and R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) category 1 recommendations for first-line therapy of follicular lymphoma.

Promising outcomes have been seen with the combination of lenalidomide plus rituximab for both rituximab-refractory and non–rituximab-refractory indolent NHL.

Bortezomib has also been used in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma.

Maintenance therapy with rituximab after induction chemotherapy has been reported to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in comparison with observation alone in patients with indolent lymphoma.

In patients with the aggressive B-cell lymphomas (e.g. diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), the standard drug combination is rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). Currently, 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy is the standard of care in patients with advanced disease. Complete disease regression is expected in ≥ 70% of patients, depending on the International Prognostic Index (IPI) category.

International Prognostic Index (IPI) for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, outlining key risk factors—age, stage, LDH level, performance status, and extranodal involvement—and corresponding 5-year survival rates across low to high-risk groups.

International Prognostic Index Calculator for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

More than 70% of complete responders are cured, and relapses > 2 years after end of treatment are rare.

Cure rates have improved with the use of R-CHOP, so autologous stem cell transplantation is reserved for patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas, some younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, and some patients with aggressive T-cell lymphomas.

A new trial found patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) had a significantly higher likelihood of survival without disease progression two years after receiving a new drug combination known as pola-R-CHP compared with those who received the standard of care R-CHOP. The findings, presented at the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, represent the first significant improvement over standard of care for newly diagnosed DLBCL reported in more than two decades, according to the authors. Although the trial found no significant difference in complete response rates or overall survival at two years, those who received the new drug combination were less likely to need additional treatment compared with those receiving R-CHOP.

R-CHOP, the current standard of care which consists of a combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, is curative in only about 60-70% of patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL. The new study compared R-CHOP to a modified drug combination that omits vincristine and includes polatuzumab vedotin along with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (pola-R-CHP). Polatuzumab vedotin was previously approved for treating patients with relapsed DLBCL.

Polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy) 140 mg, an antibody–drug conjugate used in combination regimens for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a high-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Glofitamab is a T-cell–engaging bispecific antibody possessing a novel 2:1 structure with bivalency for CD20 on B cells and monovalency for CD3 on T cells. Glofitamab was evaluated in relapsed or refractory (R/R) B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL). Data for single-agent Glofitamab, with Obinutuzumab pre-treatment to reduce toxicity, were presented.

In patients with predominantly refractory, aggressive B-NHL, Glofitamab showed favorable activity with frequent and durable CRs and a predictable and manageable safety profile.

Glofitamab (Columvi) 10 mg/10 mL, a CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody approved for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Pixantrone (Pixuveri) is an effective aza-anthracenedione with reduced cardiotoxicity and significant antineoplastic activity which may represent a therapeutic option in relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma. Pixantrone, with its activity and favorable safety profile, could represent a promising agent for novel combination regimens e.g. pixantrone-rituximab regimen, aiming to improve progression-free survival.

CNS prophylaxis, usually with 4-6 injections of Methotrexate intrathecally, is recommended for patients with paranasal sinus, tonsillar or testicular involvement, diffuse small noncleaved cell or Burkitt lymphoma, or lymphoblastic lymphoma. CNS prophylaxis for bone marrow involvement is controversial.

Treatment of acute lymphoblastic lymphoma, a very aggressive form of NHL, is similar to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) therapy. Other subtypes of high-grade lymphomas are usually treated with more aggressive variations of CHOP chemotherapy, including the addition of high-dose methotrexate or other chemotherapy drugs and higher doses of cyclophosphamide.

Management of T-cell Lymphomas:

The treatment of T-cell lymphomas continues to be challenging. T-cell lymphomas are divided into 2 subgroups: cutaneous or systemic T-cell disorders.

Typically, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are managed with topical agents and oral disease modifiers during the early stage of the disease. Systemic chemotherapy is usually incorporated late in the course of the disease with modest activity.

Systemic T-cell lymphomas represent a challenge to the practicing oncologist. Combination chemotherapy regimens – CHOP, CHOP plus etoposide, or gemcitabine-based regimens are treatment options. Alemtuzumab, Pralatrexate (Folotyn), Romidepsin (Istodax) and Belinostat (Beleodaq) are effective in selected cases.

Relapse:

The first relapse after initial chemotherapy could be treated with autologous stem cell transplantation. Patients usually should be ≤ 70 years or in equivalent health and have responsive disease, good performance status, and an adequate number of CD34+ stem cells (harvested from peripheral blood or bone marrow).

Consolidation myeloablative therapy may include chemotherapy with or without irradiation.

Posttreatment immunotherapy (eg, rituximab, vaccination, IL-2) is being studied.

An allogeneic transplant is the donation of stem cells from a compatible donor (brother, sister, matched unrelated donor, or umbilical cord blood). The stem cells have a 2-fold effect: reconstituting normal blood counts and providing a possible graft-vs-tumor effect.

In aggressive lymphoma, a cure may be expected in 30 to 50% of eligible patients undergoing myeloablative therapy and transplantation.

In indolent lymphomas, cure with autologous stem cell transplantation remains uncertain, although remission may be superior to that with secondary palliative therapy alone.

Reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation is a potentially curative option in some patients with indolent lymphoma.

The mortality rate of patients undergoing myeloablative transplantation has decreased dramatically to 2 to 5% for most autologous procedures and to < 15% for most allogeneic procedures.

Checkpoint Inhibitors: These drugs work by targeting molecules that serve as brakes on the immune response. By blocking these inhibitory molecules or, alternatively, activating stimulatory molecules, checkpoint inhibitors are designed to unleash or enhance pre-existing anti-cancer immune responses. Nivolumab (Opdivo): A PD-1 Antibody +/- Ipilimumab (Yervoy): A CTLA-4 Antibody, are currently being tested in clinical trials for patients with lymphoma.

Prognosis:

Survival rates for NHL vary widely, depending on the lymphoma type, stage, age of the patient, and other variables. According to the American Cancer Society, the overall 5-year relative survival rate for patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is 67% and the 10-year relative survival rate is 55%.

Advanced age, Stage III and IV, poor performance status and a raised LDH all predict for a poorer outcome.

Survival rates for patients with NHL have greatly improved since the early 1990s, especially for patients under age 45. Advances in treatment have contributed to this improvement.

Questions and Answers:

What is the first sign of non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

The most common early sign is painless lymphadenopathy, often in the neck, axillae, or groin. Some patients may also experience fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or abdominal fullness due to deep nodal or organ involvement.

How is non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed?

Diagnosis requires an excisional lymph node biopsy or tissue biopsy of the involved organ. Histology, immunophenotyping (flow cytometry or IHC), cytogenetics, and molecular tests such as MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 rearrangements are essential, followed by CT or PET-CT for staging.

What are B symptoms in non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

B symptoms include persistent fever above 38°C, drenching night sweats, and unintentional weight loss of at least 10% over six months, and their presence indicates a more aggressive clinical course.

What is the difference between low-grade and high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

Low-grade lymphomas such as CLL/SLL, follicular lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphoma progress slowly and may remain asymptomatic, whereas high-grade types like DLBCL or Burkitt lymphoma are rapidly growing and require urgent treatment, often responding quickly to chemotherapy.

What is the Ann Arbor stage in non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

The Ann Arbor staging system categorises disease from Stage I, involving a single nodal region, to Stage IV, involving diffuse extranodal sites such as liver, bone marrow, or lungs.

What are the most common extranodal sites of non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

Frequent extranodal sites include the stomach, small bowel, skin, bone marrow, CNS, breast, and liver or spleen, with radiologic and pathology findings helping define organ involvement.

How is DLBCL treated?

DLBCL is typically treated with R-CHOP immunochemotherapy. Relapsed or high-risk disease may require CAR-T therapy, polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy), glofitamab (Columvi), or autologous stem cell transplantation.

What is polatuzumab vedotin and how is it used in NHL?

Polatuzumab vedotin is an anti-CD79b antibody–drug conjugate used for relapsed or refractory DLBCL, usually combined with bendamustine and rituximab (Pola-BR).

What is glofitamab (Columvi) and when is it indicated?

Glofitamab is a CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody used for patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL after at least two prior lines of therapy, redirecting T cells to target malignant B cells.

What does CD5 positivity indicate in B-cell lymphomas?

CD5 positivity is characteristic of CLL/SLL and mantle cell lymphoma. Immunophenotyping patterns including CD23, FMC-7, CD79b, and CD10 help differentiate these from other B-cell lymphomas.

What factors determine prognosis in non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

Prognosis is assessed using the International Prognostic Index (IPI), incorporating age, disease stage, LDH level, performance status, and the number of extranodal sites, each correlating with distinct survival groups.

Can non-Hodgkin lymphoma affect the stomach?

Yes. Gastric DLBCL is a common extranodal presentation and typically shows gastric wall thickening on CT imaging with regional nodal involvement.

Does non-Hodgkin lymphoma spread to the brain?

CNS involvement occurs in certain high-grade lymphomas such as DLBCL, and biopsy or IHC may show CD20-positive malignant B cells infiltrating brain tissue.

What is the difference between B-cell and T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

B-cell lymphomas, which form the majority, express markers such as CD19 and CD20 and include DLBCL, follicular lymphoma, and CLL/SLL. T-cell lymphomas such as PTCL, ALCL, or mycosis fungoides have different immunophenotypes and often more aggressive behaviour.

Is radiation therapy used in non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

Yes. Radiation may be used for early-stage disease or bulky sites, with classic fields including mantle and inverted Y fields depending on nodal involvement.

How is small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) different from CLL?

SLL and CLL are biologically identical; CLL refers to circulating and marrow disease, while SLL refers to nodal-based disease. Both share the same immunophenotype, including CD5+, CD19+, and CD23+ with dim CD20 expression.

References:

Zhang QY, Foucar K. Bone marrow involvement by Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(4):873–902.

Hsia CC, Howson-Jan K, Rizkalla KS. Hodgkin lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(5):5.

Vinjamaram S. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Medscape.

Portlock CS. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas – Hematology and Oncology. Merck Manual Professional Edition.

Marazzi P. Clinical photo of the neck of a patient with a non-Hodgkin’s type lymphoma. Science Photo Library.

Bigoni R, Negrini M, Veronese ML, et al. Characterization of t(11;14) in mantle cell lymphoma by FISH. Oncogene. 1996;13:797–802.

Mac Manus MP, Bowie Rainer CA, Hoppe RT. Prognosis after relapse following primary RT for early-stage low-grade FL. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42(2):365–371.

Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine–rituximab vs R-CHOP in indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas. Lancet. 2013.

MDApp. Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (IPI) Score Calculator. https://www.mdapp.co/lymphoma-international-prognostic-index-ipi-score-calculator-344/

Czuczman MS, Rummel MJ. Recent advances in NHL: Highlights from the 51st ASH Annual Meeting. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8(2):A1–11.

Barta SK, Li H, Hochster HS, et al. Maintenance anti-CD20 antibody vs observation after induction therapy in low-grade lymphoma (E1496). Cancer. 2016.

Goy A, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Bortezomib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: PINNACLE study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(3):520–525.

Malik SM, Liu K, Qiang X, et al. FDA approval summary: Pralatrexate for relapsed/refractory PTCL. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(20):4921–4927.

Piekarz RL, Frye R, Prince HM, et al. Romidepsin in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: Phase II trial. Blood. 2011;117(22):5827–5834.

Gordon H, Harnsberger HR. Imaging Anatomy: Brain, Head and Neck, Spine. “Cervical Lymph Nodes.” Amirsys/Elsevier; 2006:253. Reproduced with permission.

Salvatorelli E, Menna P, Paz OG, et al. Pixantrone cardiac safety in doxorubicin-treated patients. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:467–478.

University of Maryland Medical Center. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma – Prognosis.

ResearchGate. Nodal Excisions and Neck Dissection Specimens for Head & Neck Tumours – Histopathology Guide. Accessed 29 Mar 2023.

American Society of Hematology (ASH).

Hematology.org. Pola-R-CHP Outperforms R-CHOP in DLBCL (2023 Progression-Free Survival Data).

Hutchings M, Morschhauser F, Iacoboni G, et al. Glofitamab induces durable complete remissions in R/R B-cell lymphoma: Phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(18):1959–1970.

Alizadeh AA, et al. Distinct types of DLBCL identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511.

Hans CP, et al. Molecular classification of DLBCL confirmed by IHC. Blood. 2004;103(1):275–282.

Wright G, et al. Gene expression–based method to classify DLBCL subgroups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(17):9991–9996.

Keywords:

non-Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL, B-cell lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, DLBCL, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, PTCL, Burkitt lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, SLL, CLL SLL immunophenotype, lymphoma immunophenotyping, CD5 positive lymphoma, CD10 positive lymphoma, lymphoma staging, Ann Arbor staging, extranodal lymphoma, gastric lymphoma, CNS lymphoma, breast lymphoma, bone marrow lymphoma, lymphoma CT findings, lymphoma PET-CT, lymphoma flow cytometry, lymphoma histopathology, lymphoma markers CD19 CD20 CD23, lymphoma treatment R-CHOP, Pola-R-CHP, polatuzumab vedotin Polivy, glofitamab Columvi, CAR-T lymphoma, lymphoma prognosis, IPI score, IPI calculator, lymphoma risk factors, lymphoma survival, lymphoma radiotherapy fields, mantle field radiation, inverted Y radiation, lymphoma management guidelines, lymphoma diagnosis, AskHematologist lymphoma, Dr Moustafa Abdou hematology

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

Hi,

Thank you for this article, This article helping people who are seeking a bit of knowledge. This would also help those people as well who are having problems with a blood disorder or blood-related medical problems. After reading this article people start caretaking themselves to prevent the problem.

Dr Gaurav Dixit

BMT Physician & Hematologist in Delhi

Very informative. Wonder if you could provide any insight – my father has bloodwork that has shown elevated WBC 32.8K/ul, Lymphocytes abs 26,535/ul, monocytes abc 1,345/ul, Eosinophils 656/ul. Beta-2-microglobulin 3.24.

The hematologist he went to see has told him definitively it is SLL, and it is very slow progressing, stage 0, and she will see him in 3 months.

Are you able to diagnose based on this blood work alone?? Everything I read talks about the necessity of imaging for proper diagnosis, and especially proper staging. Also the doubling time for his Lymphocytes is currently 3.5 months, which seems to be an adverse marker for progression. Would love to know your thoughts. Trying to get in to see other doctors ASAP and no one is available for months. Thank you!!

Hi Kristina,

Thank you for your comment.

If it is SLL stage 0 active monitoring should be enough if not associated with B symptoms (night sweats, significant weight loss, recurring fever).

However, I would suggest for completion of the investigations:

1- Blood flow cytometry.

2- ESR.

3- Serum LDH.

4- Serum immunoglobulins and protein electrophoresis.

5- The biochemistry profile (renal and liver function tests).

5- CT scan of Neck/Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis.

BW,

Hi I am 56 year old male have been diagnosed ebv mono at hospital 8 weeks ago , since then I am feeling much better but I lost about 14lbs in a couple of weeks and have not been able to put back on but diet has changed, nodes in neck are more sore the last few days than have been at any time but , I have had slight pain in chest but think it could be down to anxiety, blood pressure fine ECG also fine, don’t feel good after light exercise short walk etc, have had scaily patches of skin on right leg calf area, also left elbow for approx 12 years or more but elbow in last few weeks as also turned bumps , i am worried it could be misdiagnosed and could be lymphoma , it came on sudden had fever crp was close to 50 wbc was low went down to 0.9 ,after taking one folic acid tablet levels started to improve slowly , i have had many thoughts going through my mind . I know it’s not good for my mental health to Google symptoms but it looks like ebv mono at my age is rare and ebv shows up in blood with lymphoma but would levels go up and down like that with lymphoma , I have to see my GP in a week should they send me for a test for lymphoma

Hi Leo,

Thank you for reaching out.

Your concerns are completely valid, especially given the symptoms you’ve described and your recent history with EBV mononucleosis.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can lead to a wide range of symptoms, and recovery can be prolonged.

However, the possibility of lymphoma as a differential diagnosis needs careful consideration, particularly in light of weight loss and persistent lymph node symptoms and other factors you’ve mentioned.

Generally speaking, lymphoma typically presents with painless lymph node enlargement, though pain can sometimes occur, particularly if nodes are compressing nearby structures.

I recommend initially undergoing a neck ultrasound to assess the lymph nodes more thoroughly.

Additionally, repeating EBV serology (IgM and IgG) could help determine the current state of the infection.

Along with this, testing for Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) levels can provide further insights into any ongoing inflammation or potential tissue involvement.

These tests can help clarify whether the persistent symptoms are due to prolonged effects of EBV or if further investigations, such as a biopsy or advanced imaging, might be necessary.

Please make sure to clearly communicate all your concerns to your GP.

Best wishes,

Dr. M. Abdou