Hodgkin’s Disease

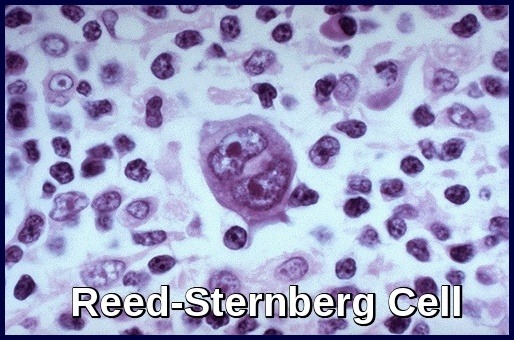

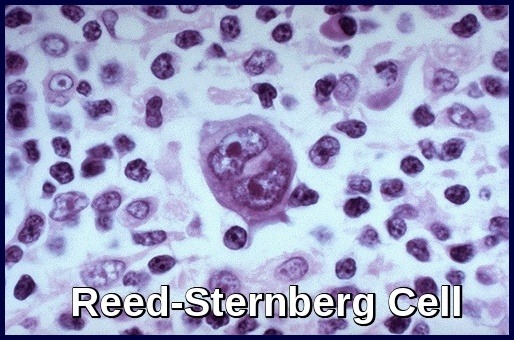

Reed–Sternberg cell, a hallmark feature of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, shown on high-power microscopic examination.

Hodgkin’s Disease (Hodgkin’s Lymphoma) is a malignant neoplasm that usually arises in a lymph node.

It results from the clonal transformation of cells of B-cell origin, giving rise to pathognomonic binucleated Reed-Sternberg cells (RS cells). The nature of the malignant RS cell remains uncertain. Clonally integrated Epstein-Barr virus is present in the RS cells in about 40% of cases.

The cause is unknown, but genetic susceptibility and environmental associations (e.g. occupation, such as woodworking; history of treatment with phenytoin, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy; infection with Epstein-Barr virus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, herpesvirus type 6, HIV) play a role.

The risk is slightly increased in people with certain types of immune suppression (e.g. post-transplant patients taking immunosuppressants); in people with congenital immunodeficiency disorders (e.g. ataxia-telangiectasia, Klinefelter syndrome, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome); and in people with certain autoimmune disorders (RA, celiac sprue, Sjögren syndrome, SLE).

Most patients also develop a slowly progressive defect in cell-mediated immunity that, in advanced disease, contributes to common bacterial and unusual fungal, viral, and protozoal infections.

Humoral immunity (antibody production) is depressed in advanced disease.

Hodgkin lymphoma is a potentially curable lymphoma.

Death often results from sepsis.

In the US, about 9000 new cases of Hodgkin lymphoma are diagnosed annually. The male:female ratio is 1.4:1.

Hodgkin’s disease is rare before age 10 and is most common between ages 15 and 40; a second peak occurs in people > 50-60.

Clinical features:

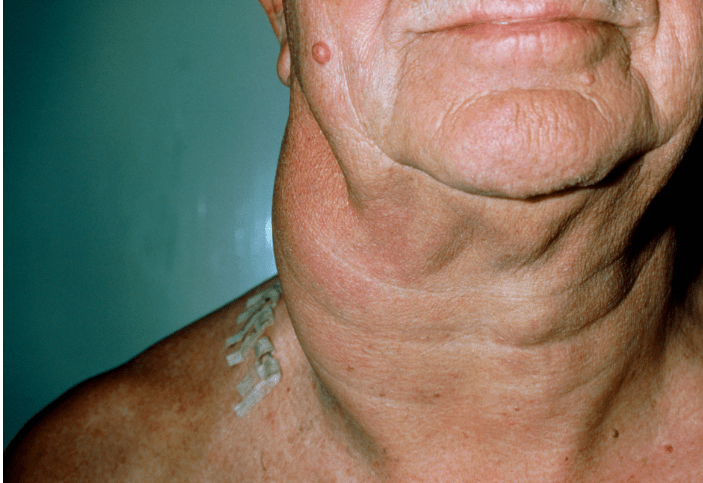

Asymptomatic lymphadenopathy may be present (above the diaphragm in 80% of patients).

Constitutional symptoms (unexplained weight loss >10% of total body weight within the past 6 months, unexplained fever >38º C, or drenching night sweats) are present in 40% of patients; collectively, these are known as “B symptoms“.

Intermittent fever is observed in approximately 35% of cases; infrequently, the classic Pel-Ebstein fever is observed (high fever for 1-2 wk, followed by an afebrile period of 1-2 wk).

Pel-Ebstein fever pattern, a classic but uncommon clinical feature historically linked with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

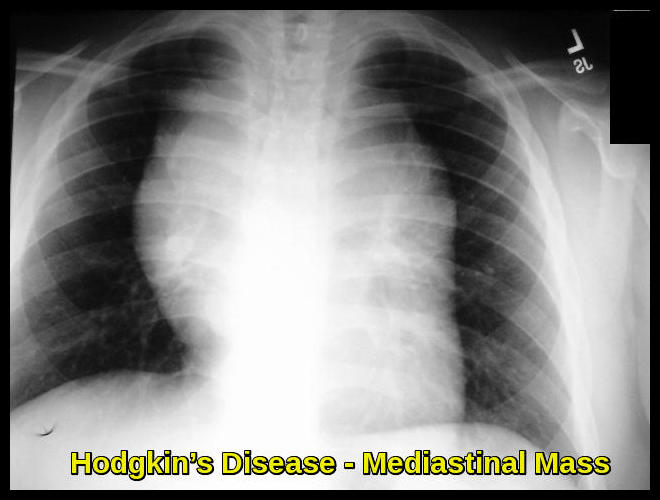

Chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, or a combination of those may be present due to a large mediastinal mass or lung involvement; rarely, hemoptysis occurs.

Pruritus may be present.

Pain at sites of nodal disease, precipitated by drinking alcohol, occurs in fewer than 10% of patients but is specific for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Back or bone pain may rarely occur.

A family history is also helpful; in particular, nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL) has a strong genetic component and has often previously been diagnosed in the family.

Physical examination findings in Hodgkin lymphoma include the following:

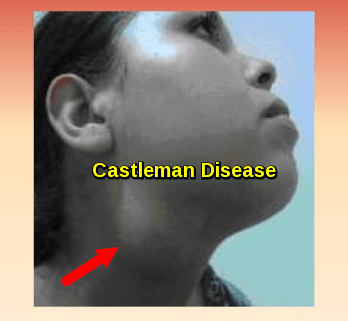

Palpable, painless lymphadenopathy can be seen in the cervical area (60-80%), axilla (6-20%), and, less commonly, in the inguinal area (6-20%).

Involvement of the Waldeyer ring (back of the throat, including the tonsils) or occipital or epitrochlear areas is infrequently observed.

Splenomegaly and/or hepatomegaly may be present.

Superior vena cava syndrome may develop in patients with massive mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms or signs may be due to paraneoplastic syndromes, including cerebellar degeneration, neuropathy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, or multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Diagnosis:

Hodgkin’s disease is usually suspected in patients with painless lymphadenopathy or mediastinal adenopathy detected on routine chest x-ray.

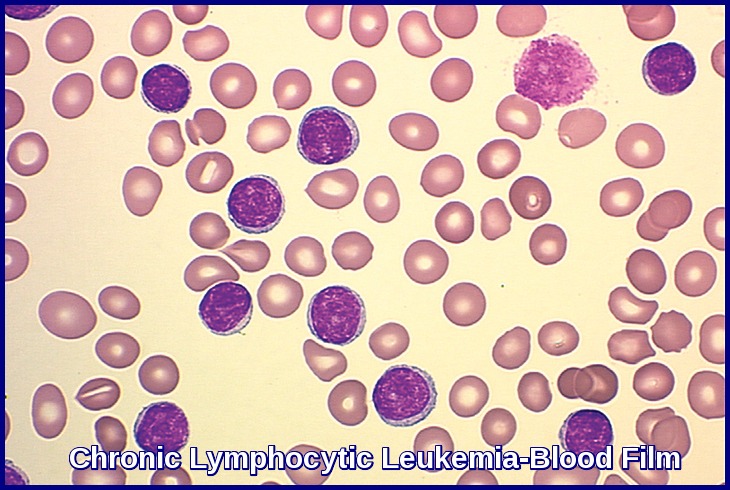

Similar lymphadenopathy can result from infectious mononucleosis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus infection, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or leukemia.

Similar chest x-ray findings can result from lung cancer, sarcoidosis, or TB.

Chest x-ray:

Chest X-ray demonstrating a bulky mediastinal mass, a classic radiologic finding in Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis: imaging studies can help to define disease bulk, which has prognostic implications. The definition of the bulky disease varies, but in general, is defined as any nodal mass greater than 10 cm and a mediastinal mass greater than one-third the thoracic diameter as measured at T5/6.

Blood tests: FBC for anemia, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, or eosinophilia, ESR, alkaline phosphatase, LDH, liver function tests, albumin, Ca, U&Es, and creatinine.

HIV and Hepatitis serology.

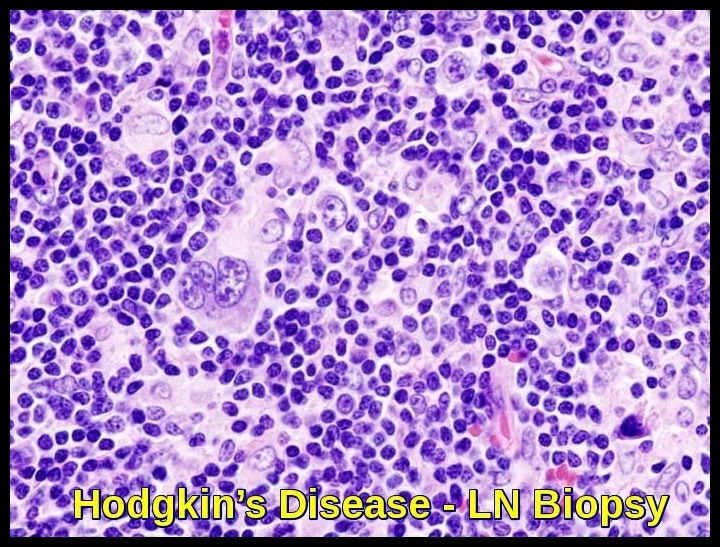

Lymph node biopsy:

Lymph node biopsy demonstrating classic Reed–Sternberg cells, the defining histologic feature of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

A histologic diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease is always required. An excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended because the lymph node architecture is important for histologic classification.

When a patient presents with neck lymphadenopathy and risk factors for a head and neck cancer, a fine-needle aspiration is usually advised as the initial diagnostic step, followed by an excisional biopsy if squamous cell histology is excluded.

If only mediastinal nodes are enlarged, mediastinoscopy may be indicated.

A CT-guided biopsy may also be considered.

Biopsy reveals Reed-Sternberg cells (large, binucleated cells) in a characteristically heterogeneous cellular infiltrate, consisting of histiocytes, lymphocytes, monocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils.

Positron emission tomography (PET Scan): Considered essential to the initial staging of Hodgkin lymphoma.

PET scan demonstrating widespread FDG uptake in Hodgkin’s lymphoma at diagnosis, with near-complete metabolic response after two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy.

MRI if neurologic symptoms are present.

Bone marrow biopsies are indicated in some cases. Bone marrow involvement is more common in elderly patients and those with advanced-stage disease, systemic symptoms, or a high-risk histology. However, given the low incidence of bone marrow involvement, some experts and expert groups feel that bone marrow biopsy can be omitted, particularly in early-stage disease.

Histopathologic Subtypes:

WHO classification table of histopathologic subtypes of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, including classic and nodular lymphocyte-predominant forms.

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma has 4 histopathologic subtypes; there is also a lymphocyte-predominant type. Certain antigens on Reed-Sternberg cells may help differentiate Hodgkin lymphoma from non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and classic Hodgkin lymphoma from the lymphocyte-predominant type.

Staging:

Ann Arbor staging system for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, showing lymph node involvement patterns and progression from stage I to stage IV.

Involvement of the liver or the bone marrow is considered stage IV disease. For staging classifications, the spleen is considered to be a lymph node area. Involvement of the spleen is denoted with the S suffix (i.e. IIBS).

An “X” designation is sometimes used to indicate the presence of bulky disease (i.e. bulk >10 cm).

The spread of Hodgkin lymphoma takes place via the lymphatics, hematogenous routes, and direct extension. Contiguous involvement of extranodal sites (e.g. involvement of the lung parenchyma due to direct extension of large mediastinal lymphadenopathy) is not considered stage IV disease. Rather, it is designated with the E suffix (i.e. IIBE).

Treatment:

The choice of treatment modality is complex and depends on the precise stage of the disease.

Before treatment, men should be offered sperm banking, and women should discuss fertility options with their Hematologists.

Hodgkin’s disease is considered to be a curable malignancy, but therapies for this disease can have significant long-term toxicity.

General treatment modalities include radiation therapy, induction chemotherapy, salvage chemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

In general, the management of Hodgkin lymphoma depends on the subtype. Most clinicians divide classical Hodgkin lymphoma into the following three general groups:

- Early-stage favorable

- Early-stage unfavorable

- Advanced-stage disease

The EORTC (European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer) definition of favorable disease uses the following patient criteria:

- Limited-stage disease

- Age younger than 50 years

- No bulky mediastinal adenopathy

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) less than 50 mm/h

- No B symptoms (or an ESR <30 mm/h with B symptoms)

- Three or fewer sites of involvement

Stage IA, IIA, IB, or IIB disease is generally treated with an abbreviated ABVD Chemotherapy regimen (doxorubicin,bleomycin,vinblastine, and dacarbazine) plus Radiation Therapy or with longer-course chemotherapy alone. Such treatment cures about 80% of patients.

In patients with bulky mediastinal disease, chemotherapy may be of longer duration or of a different type, and radiation therapy is typically used.

Stage IIIA and IIIB disease are usually treated with ABVD combination chemotherapy alone. Cure rates of 75 to 80% have been achieved in patients with stage IIIA disease, and rates from 70 to 80% in patients with stage IIIB disease.

For stage IVA and IVB disease, ABVD combination chemotherapy is the standard regimen, producing complete remission in 70 to 80% of patients; > 50% remain disease-free at 5 years.

Other effective drug combinations include BEACOPP Chemotherapy regimen (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) and Stanford V Chemotherapy regimen (mechlorethamine, doxorubicin, vinblastine, vincristine, etoposide, bleomycin, prednisone). Standford V incorporates involved field irradiation for consolidation.

Lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin disease (LPHD) is a unique clinical entity characterized by indolent nodal disease that tends to relapse after standard radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The malignant cells of LPHD are CD20+ and therefore Rituximab may have activity with fewer late effects than standard therapy. In a phase 2 trial, 22 patients with CD20+ LPHD received 4 weekly doses of rituximab at 375 mg/m2. Ten patients had previously been treated for Hodgkin disease, while 12 patients had untreated disease. All 22 patients responded to rituximab (overall response rate, 100%) with complete response (CR) in 9 (41%), unconfirmed complete response in 1 (5%), and partial response in 12 (54%). Acute treatment-related adverse events were minimal. With a median follow-up of 13 months, 9 patients had relapsed, and estimated median freedom from progression was 10.2 months. Progressive disease was biopsied in 5 patients: 3 had recurrent LPHD, while 2 patients had transformation to large-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (LCL). All 3 patients with recurrent LPHD were retreated with rituximab, with a second CR seen in 1 patient and stable disease in 2. Rituximab induced prompt tumor reduction in each of 22 LPHD patients with minimal acute toxicity; however, based on the relatively short response duration seen in the trial and the concerns about transformation, rituximab should be considered investigational treatment for LPHD.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) is a monoclonal antibody which targets a protein called CD30 that is found on Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells. It is used in the treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous stem cell transplant or after failure of at least two prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not candidates for autologous stem cell transplant.

Checkpoint Inhibitors: These drugs work by targeting molecules that serve as brakes on the immune response. By blocking these inhibitory molecules or, alternatively, activating stimulatory molecules, checkpoint inhibitors are designed to unleash or enhance pre-existing anti-cancer immune responses. Nivolumab (Opdivo): A PD-1 Antibody +/- Ipilimumab (Yervoy): A CTLA-4 Antibody, are currently being tested in clinical trials for patients with lymphoma.

On May 17, 2016, nivolumab (Opdivo) was granted accelerated approval by FDA for treatment of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and post-transplantation brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris).

Autologous stem cell transplantation should be considered for all physiologically eligible patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s disease who respond to salvage chemotherapy.

Management of Hodgkin’s disease in pregnancy:

The priority must be the health of the mother and ideally management should be in conjunction with an obstetrician experienced in high-risk pregnancy.

While termination of pregnancy may be the most appropriate course of action for certain patients, for many cases, the fetal and maternal outcomes following Hodgkin lymphoma treatment in pregnancy appear excellent.

Staging and response assessment with MRI scanning and ultrasound may avoid the need for radiation-based imaging, and in certain cases, delaying therapy until postpartum may be possible, although this must be done with caution.

If therapy is required in pregnancy, the general consensus is that ABVD is the regimen of choice if multi-agent chemotherapy is to be used.

Although ABVD has been used to treat patients in all 3 trimesters, the potential risk to fetal development from chemotherapy is likely to be higher in the first trimester and most clinicians would try and avoid exposure to chemotherapy at this time.

Wherever possible, RT should be delayed until post delivery.

Follow up:

Patients with Hodgkin’s disease are usually followed with 3-6 monthly outpatient clinical review for 5 years following first line therapy.

There is no proven role for routine surveillance CT or PET/CT imaging in patients with Hodgkin’s disease who are otherwise well following first line therapy.

Patients with Hodgkin’s disease should be made aware that they are at an increased lifetime risk of second neoplasms, cardiovascular and pulmonary disease and

infertility.

Apart from the current breast cancer screening programme in the UK, there are no national cancer screening programmes tailored for Hodgkin’s disease survivors. Women treated with mediastinal radiotherapy before the age of 35 years should be offered entry into the breast cancer National Notification Risk Assessment and Screening programme (NRASP).

Regular lifestyle advice should be offered to reduce the secondary neoplasms and cardiovascular risk. There should be complete avoidance of smoking and careful management of cardiovascular risks such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia.

Patients with Hodgkin’s disease who have had radiotherapy to the neck and upper mediastinum should have regular thyroid function checks. Hypothyroidism can occur up to 30 years after radiotherapy.

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma should receive irradiated blood products for life in view of their defective T-cell function.

Prognosis:

In classic Hodgkin lymphoma, disease-free survival 5 years after therapy is considered a cure. Relapse is very rare after 5 years. Chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy achieves cure in 70 to 80% of patients.

Increased potential for relapse depends on many factors, including male sex, age > 45 years, involvement of multiple extranodal sites, and the presence of constitutional symptoms at diagnosis (B symptoms).

Patients who do not achieve complete remission or who relapse within 12 months have a poor prognosis.

Summary:

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a highly curable lymphoid malignancy characterised by Reed–Sternberg cells, predictable patterns of lymphatic spread, and strong responsiveness to modern therapies such as ABVD and PET-adapted treatment strategies. Early recognition of symptoms, accurate staging with PET/CT, and timely initiation of evidence-based chemotherapy or combined-modality treatment significantly improve long-term survival. Ongoing research continues to refine risk-adapted approaches and incorporates novel agents like checkpoint inhibitors for relapsed or refractory disease, reinforcing the importance of personalised management to achieve optimal outcomes.

Questions and Answers:

What are the early symptoms of Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

Early symptoms often include painless cervical, axillary, or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, persistent fatigue, night sweats, prolonged fever, unexplained weight loss, and sometimes pruritus or chest pressure due to a mediastinal mass.

What is the significance of Reed–Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

Reed–Sternberg cells are the diagnostic hallmark of classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma, confirming the diagnosis on lymph node biopsy and distinguishing the disease from non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

How is Hodgkin’s lymphoma staged?

Staging uses the Ann Arbor system and is based on nodal regions involved, disease location relative to the diaphragm, extranodal involvement, and the presence of B symptoms, with PET/CT being the standard tool for accurate staging.

What is Pel-Ebstein fever in Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

Pel-Ebstein fever is a rare cyclic fever pattern of alternating febrile and afebrile periods that has historically been associated with Hodgkin’s lymphoma but is uncommon in current practice.

What does a PET scan show in Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

PET scans show FDG-avid lymph nodes or extranodal disease at diagnosis and assess metabolic response during treatment, with early PET negativity strongly predicting favourable outcomes.

What are the main subtypes of Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

The main subtypes include classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte-rich, lymphocyte-depleted) and nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL, each with distinctive histology and immunophenotype.

How is Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated?

Standard treatment consists of ABVD chemotherapy with or without involved-site radiotherapy. PET-adapted strategies guide escalation or de-escalation, while relapsed or refractory cases may require autologous stem cell transplantation or checkpoint inhibitors.

Is Hodgkin’s lymphoma curable?

Yes, Hodgkin’s lymphoma is one of the most curable malignancies, with survival rates above 85–90% in early stages and over 70% in advanced stages when modern therapies are applied.

What are B symptoms in Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

B symptoms include fever, drenching night sweats, and unexplained weight loss, and help classify patients into A or B categories while providing important prognostic information.

What causes a mediastinal mass in Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

A mediastinal mass typically results from bulky lymphadenopathy, most often in the nodular sclerosis subtype, and can present with cough, chest tightness, dyspnoea, or features of superior vena cava compression.

References:

Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001.

Hentrich M, Maretta L, Chow KU, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy improves survival in HIV-associated Hodgkin’s disease: results of a multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(6):914–919.

Vassilakopoulos TP, Angelopoulou MK, Constantinou N, et al. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for bone marrow involvement in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105(5):1875–1880.

Portlock CS. Hodgkin Lymphoma. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Available from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/lymphomas/hodgkin-lymphoma

Lash BW. Hodgkin Lymphoma: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Medscape. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/201886-overview

Connors JM. State-of-the-art therapeutics: Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(26):6400–6408.

Cosset JM, Henry-Amar M, Meerwaldt JH, et al. EORTC trials for limited-stage Hodgkin’s disease. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A(11):1847–1850.

Bachanova V, Connors JM. How is Hodgkin lymphoma in pregnancy best treated? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;33–34.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Nivolumab (Opdivo) for Hodgkin lymphoma. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/informationondrugs/approveddrugs/ucm501412.htm

Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Opdivo (nivolumab) injection prescribing information. 2016. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125554s019lbl.pdf

Ekstrand BC, Lucas JB, et al. Rituximab in lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin disease: results of a phase 2 trial. Blood. 2003;101(11):4285–4290.

Keywords:

Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, Reed–Sternberg cells, cervical lymphadenopathy, mediastinal mass, Pel-Ebstein fever, Hodgkin lymphoma staging, Ann Arbor staging, Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis, Hodgkin lymphoma PET scan, FDG-avid lymph nodes, ABVD chemotherapy, chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma, PET-adapted therapy, Hodgkin lymphoma treatment, lymph node biopsy, classic Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma, mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma prognosis, Hodgkin lymphoma survival, Hodgkin lymphoma B symptoms, advanced Hodgkin lymphoma, early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma, refractory Hodgkin lymphoma, checkpoint inhibitors Hodgkin lymphoma, nivolumab Hodgkin lymphoma, immunotherapy Hodgkin lymphoma, ABVD regimen, PET-CT Hodgkin lymphoma, bone marrow involvement Hodgkin lymphoma, HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma, pregnancy Hodgkin lymphoma management, bulky mediastinal disease.