Hemophagocytosis

Introduction:

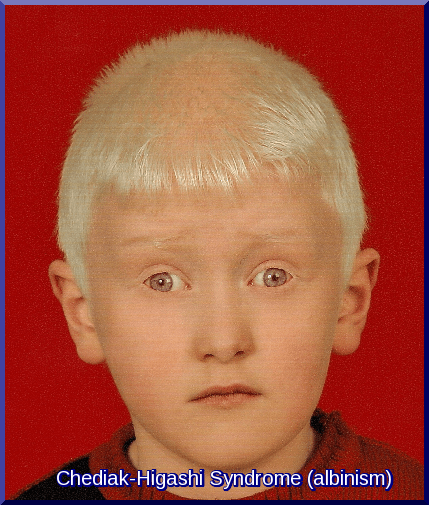

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytosis, is a rare but life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome caused by uncontrolled activation of the immune system. It results from defects in natural killer (NK) cell and cytotoxic T-cell regulation, leading to excessive cytokine release and accumulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes in multiple organs. These overactive immune cells can attack the body’s own tissues, including red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets, causing pancytopenia and organ dysfunction. HLH can occur as a genetic (primary) form, usually presenting in infancy, or as an acquired (secondary) form triggered by infections, malignancies, or autoimmune diseases. Early recognition and prompt treatment are crucial, as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis carries a high mortality rate if left untreated.

Types:

Hemophagocytosis can be:

Familial (primary)

Acquired (secondary)

Hemophagocytosis is diagnosed when patients fulfill at least 5 of the criteria described below or have a mutation in a known HLH-associated gene. The presence of a PRF1 gene mutation can be determined based on flow cytometry by staining perforin contained in lymphocytes.

Acquired hemophagocytosis can be associated with other disorders (e.g. leukemias, lymphomas, SLE, RA, polyarteritis nodosa, sarcoidosis, progressive systemic sclerosis, Sjögren syndrome, Kawasaki disease) and can occur in kidney or liver transplant recipients. Acquired HLH may be caused by those disorders or the immunosuppressive regimens used to treat them, and possibly by infections. Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS) is a life-threatening complication of rheumatic disease that, for unknown reasons, occurs much more frequently in individuals with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) and in those with adult-onset Still disease.

In both familial and acquired forms, genetic abnormalities, clinical manifestations, and outcomes tend to be similar.

Irrespective of the cause, the unrestrained immune hyperactivation leads to host tissue damage and a characteristic clinical syndrome.

Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, and rash often comprise the initial presentation.

Pathophysiology:

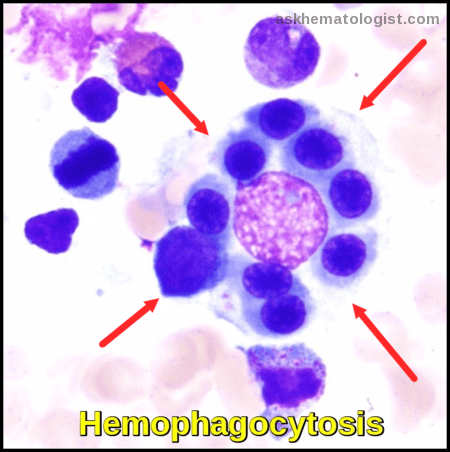

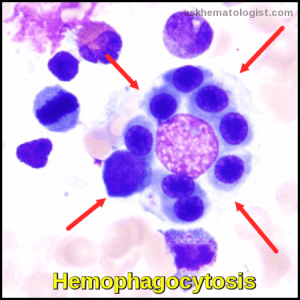

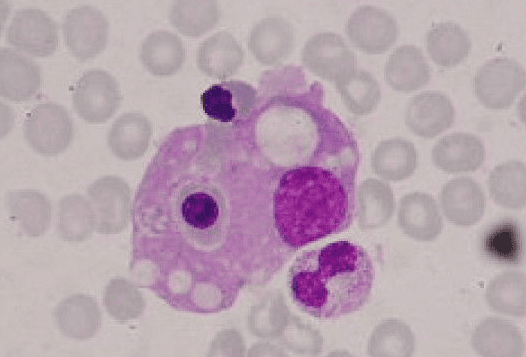

The pathological hallmark of this disease is the aggressive proliferation of activated macrophages and histiocytes, which phagocytose other cells, namely RBCs, WBCs, and platelets, leading to the clinical symptoms.

The uncontrolled growth is nonmalignant and does not appear clonal in contrast to the lineage of cells in Langerhans cells histiocytosis (histiocytosis X). The spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, skin, and membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord are preferential sites of involvement.

This disorder may be viewed as a highly stimulated, but ineffective, immune response to antigens, which results in life-threatening cytokine storm and inflammatory reaction.

Clinical Features:

HLH can be diagnosed if there is a mutation in a known causative gene or if at least 5 of 8 diagnostic criteria are met:

- Fever (peak temperature of > 38.5° C for > 7 days).

- Splenomegaly (spleen palpable > 3 cm below costal margin).

- Cytopenia involving > 2 cell lines (Hb < 9 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count < 100/μL, platelets < 100,000/μL).

- Hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglycerides > 2.0 mmol/L) or hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen < 1.5 g/L).

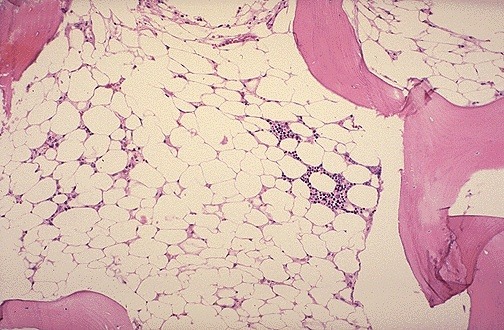

- Hemophagocytosis (in biopsy samples of bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes).

- Low or absent natural killer (NK) cell activity. Because NK cell function or activity is decreased in as many as 90% of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), it is one of the most useful laboratory tests. NK cell number is usually not diagnostic.

- Serum ferritin > 500 μg/L.

- Elevated soluble IL-2 (CD25) levels (>2400 U/mL or very high for age).

- Liver damage has also been reported as evidenced by hyperbilirubinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated findings on liver function tests including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Bone marrow aspirate showing prominent hemophagocytosis. Histiocyte ingesting red and white cell precursors

Treatment:

Treatment should be started if the disorder is suspected, even if not all diagnostic criteria are fulfilled.

Patients are usually treated by a pediatric hematologist and in a referral center experienced in treating patients with HLH.

Treatment depends on the presence of factors such as a family history of HLH, coexisting infections, and demonstrated immune system defects.

In 1994, as a result of an international cooperative effort, the Histiocyte Society created the first treatment protocol for patients with HLH/FHL. This included a combination of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and steroids, as well as antibiotics and antiviral drugs, followed by a stem-cell transplant in patients with persistent or recurring HLH or those with Familial Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (FHL).

The HLH-2004 protocol was based on the HLH-94 protocol with minor changes such as cyclosporine, an immunosuppressant drug, being started at the onset of therapy rather than week 8. This protocol has been widely accepted internationally and is used in numerous countries on all continents but should only be used as a research study.

While optimal treatment of HLH is still being debated, current treatment regimens usually involve high dose corticosteroids, etoposide, and cyclosporine.

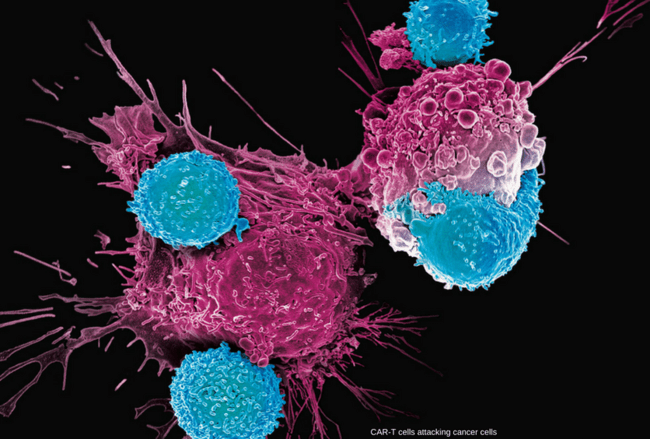

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is also used. Methotrexate and vincristine have also been used. Other medications include cytokine targeted therapy.

There are cases of secondary HLH that can resolve spontaneously or after treatment of the underlying disease, without the use of chemotherapy. The treatment should be guided in part by the severity of the condition, as well as the cause of the disease.

FHL, however, when not treated, is usually rapidly fatal with an average historical survival of about 2 months. The treatment included in the HLH-2004 research protocol is intended to achieve stability of the disease symptoms so that a patient can then receive a stem-cell transplant, which is necessary for a cure.

In recent years, some transplant centers have adopted the use of reduced intensity conditioning (or “RIC”) to prepare for the stem cell transplant. This approach offers the possibility of better survival with stem cell transplant than the intensive chemotherapy protocols previously used.

As research continues, the outcome for patients with HLH/FHL has improved greatly in recent years. Approximately two-thirds of children with HLH who undergo transplantation can expect to be cured of their disease. However, there are a number of complications that can occur during the process of transplant, including severe inflammatory reactions, anemia, and graft-versus-host disease.

Long-term follow-up of survivors of transplants for HLH/FHL indicates that most children return to a normal or near-normal quality of life. The results of transplantation are generally better when the procedure is performed at a major pediatric transplant center where the doctors are familiar with this disease. Early and accurate diagnosis is essential.

However, there is still a high rate of death, indicating the education of the medical community regarding prompt diagnosis and management of the diseases, as well as improvement in managing therapy to provide optimal outcome still requires support for clinical research of this group of disorders.

References:

Henter JI, Horne A, Aricò M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

La Rosée P, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465–2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618

Aricò M, Allen M, Brusa S, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: proposal of a diagnostic algorithm based on perforin expression. Br J Haematol. 2002;119(1):180–188.

Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davì S, et al. 2016 Classification Criteria for Macrophage Activation Syndrome Complicating Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):481–489.

Janka GE. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematology. 2005;10:104–107.

Tang Y, Xu X. Advances in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: pathogenesis, early diagnosis/differential diagnosis, and treatment. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:697–708.

Rajagopala S, Singh N, Agarwal R, Gupta D, Das R. Severe hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults – experience from an intensive care unit from North India. https://goo.gl/gqPW5b

National Institutes of Health (NIH) / MedlinePlus. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/hemophagocytic-lymphohistiocytosis

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – NIH. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6628/hemophagocytic-lymphohistiocytosis

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hemophagocytic Syndrome – Rare Inflammatory Conditions. https://www.cdc.gov

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) – Overview and Management. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hemophagocytic-lymphohistiocytosis

Jeffrey M. Lipton, MD, PhD. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) – Hematology and Oncology – Merck Manuals Professional Edition. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/histiocytic-syndromes/hemophagocytic-lymphohistiocytosis-hlh

Robert A. Schwartz, MD, MPH; Max J. Coppes, MD, PhD, MBA. Lymphohistiocytosis (Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/986458-overview

Histiocytosis Association. Hemophagocytic Syndromes – Diagnosis and Treatment. https://www.histio.org/page.aspx?pid=389#

Keywords:

hemophagocytosis, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, HLH, primary HLH, secondary HLH, hemophagocytosis causes, hemophagocytosis diagnosis, hemophagocytosis treatment, hemophagocytosis hematology, HLH cytokine storm, HLH treatment protocols, HLH symptoms, HLH prognosis, hemophagocytosis bone marrow biopsy, macrophage activation syndrome, hematology rare disorder, Ask Hematologist, Dr Moustafa Abdou

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

this website is very useful as hemotholgy is important for every subject.