Coronavirus and Blood

Coronavirus (COVID-19) illustrating viral spike proteins implicated in immune activation, coagulopathy, and blood abnormalities

Coronavirus and Blood:

Does coronavirus have direct effects on Blood?

The COVID-19 pandemic has become one of the most significant global public health crises in a century. Since its emergence in December 2019, the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has infected millions worldwide and caused widespread morbidity and mortality. Beyond its respiratory manifestations, COVID-19 also affects the hematologic system, leading to various COVID-19 blood disorders such as thrombosis, lymphopenia, anemia, and coagulation abnormalities. Research has shown that SARS-CoV-2 may alter red blood cell (RBC) membrane proteins, impair oxygen transport, and trigger hypercoagulability in severely ill patients. According to Steven Spitalnik and colleagues at Columbia University, altered protein-membrane homeostasis can promote clot formation and contribute to the coagulation complications commonly seen in advanced COVID-19 cases.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Scanning electron microscope image showing SARS-CoV-2 particles (gold-coloured) emerging from the surface of infected cells in laboratory culture. SARS-CoV-2 is the virus responsible for COVID-19–associated hematological and thrombotic complications. Image credit: NIAID-RML

Susceptibility of RBCs to SARS-CoV-2:

The causative agent – SARS-CoV-2 – infects cells by using its Spike protein to bind host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and fuse with the cell membrane. This ACE2 receptor is abundantly expressed on lung alveolar epithelial cells.

According to Spitalnik and colleagues, proteomics studies have previously identified angiotensin and ACE2-interacting proteins on the surface of RBCs, suggesting that these cells may be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 invasion.

Since RBCs are responsible for transporting oxygen around the body, their alteration may contribute to the severity of hypoxemia among patients with severe COVID19, suggests the team.

Because RBCs are critical for oxygen transport and off-loading, the severely low oxygen saturations seen in critically ill COVID-19 patients suggest the importance of determining whether SARS-CoV-2 infection directly or indirectly affects RBC metabolism to influence their gas transport, structural integrity, and circulation in the bloodstream,” they write.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Critically ill patient receiving intensive care unit (ICU) support, illustrating severe COVID-19 associated with systemic inflammation, coagulopathy, and hematological complications

Other hematological findings in SARS patients:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has recently recognized as a new human infectious disease. A novel coronavirus was identified as the causative agent of SARS. This report summarizes the hematological findings in SARS patients and proposes a hypothesis for the pathophysiology of SARS coronavirus related abnormal hematopoiesis.

Hematological changes in patients with SARS were common and included lymphopenia (68% – 90% of adults; 100% of children, n = 10), thrombocytopenia (20% – 45% of adults, 50% of children), and leukopenia (20% – 34% of adults, 70% of children). The possible mechanisms of this coronavirus on the blood system may include (1) directly infect blood cells and bone marrow stromal cells via CD13 or CD66a; and/or (2) induce autoantibodies and immune complexes to damage these cells. In addition, lung damage in SARS patients may also play a role in inducing thrombocytopenia by (1) increasing the consumption of platelets/megakaryocytes; and/or (2) reducing the production of platelets in the lungs. Since the most common hematological changes in SARS patients were lymphopenia and immunodeficiency, it is postulated that hematopoietic growth factors such as G-CSF, by mobilizing endogenous blood stem cells and endogenous cytokines, could become a hematological treatment for SARS patients, which may enhance the immune system against these viruses.

Detection of Virus in Human Blood or Blood Cells:

A recent study by researchers in Cairo, Egypt, and published on the preprint server medRxiv was designed to test for the presence of the virus in human blood or any blood cells, which could allow the virus to hide from the immune system or to be trafficked to other organs. It is especially relevant given some (doubtful) reports that the virus could infect lymphocytes.

Other scientists have claimed that the virus perhaps attacks hemoglobin, or that it is to be found in the blood of infected patients, or the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), as is the case with other infectious viruses like hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HIV.

The current study, therefore, used computational analysis on three genome sequences from PBMCs from active COVID-19 patients, three from healthy donor PBMCs, and two from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) from patients. They found that traces and large amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA were found in PBMCs and BAL, respectively.

The results showed that the BAL and PBMC samples were widely separated, as expected, while the PBMCs from healthy and patient samples were slightly separated for the most part. Viral RNA was present in all the BALF sequences at 2.15% of the total reads (median). The PBMC of one patient also showed two reads that matched the SAR-CoV-2 protein and surface glycoprotein.

Though the amount of viral RNA is small, it is undoubtedly that of the SARS-CoV-2. One of the reads encodes a polyprotein, which takes part in viral transcription and replication, and which is the largest of the coronavirus proteins. Another encoded the spike protein, which is responsible for the viral entry into human cells that carry the ACE2 molecule receptor.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Peripheral blood film showing reactive (atypical) lymphocytes, a recognized hematological finding in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection

Coronavirus and Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

Frequently Asked Questions

How do we diagnose PE if we cannot perform CTPA or V/Q lung scan because the patient must remain in isolation (e.g. due to risk of virus aerosolization, lack of PPE) or is too unstable?

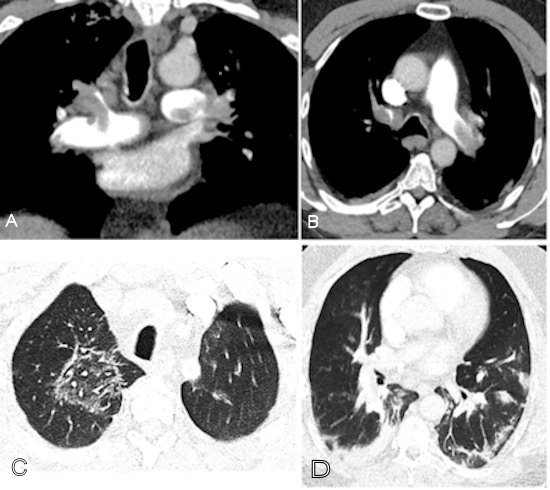

When objective imaging is not feasible to confirm or refute a diagnosis of PE, clinicians must rely on clinical assessment based on history, physical findings, and other tests. Very limited observational data suggest that up to 15-39% of patients with COVID-19 infection who require mechanical ventilation have acute PE/DVT. The likelihood of PE is moderate to high in those with signs or symptoms of DVT, unexplained hypotension or tachycardia, unexplained worsening respiratory status, or traditional risk factors for thrombosis (e.g., history of thrombosis, cancer, hormonal therapy). If feasible, consider doing bilateral compression ultrasonography (CUS) of the legs, echocardiography, or point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS). These tests can confirm thrombosis if proximal DVT is documented on CUS or if a clot-in-transit is visualized in the main pulmonary arteries on echocardiography or POCUS, but they cannot rule out thrombosis if a clot is not detected.

Data suggested an increased PE prevalence in COVID-19 patients attending ED with an elevated D-dimer, and patients with levels >5000 ng/ml might benefit from CTPA to exclude concomitant PE.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) in a COVID-19–positive patient with markedly elevated D-dimer (>10,000) demonstrating extensive bilateral pulmonary emboli and characteristic lung involvement. (A) Coronal CTPA shows emboli involving the left main pulmonary artery, distal right main pulmonary artery, right upper lobe pulmonary artery, and proximal segmental branches. (B) Axial CTPA image demonstrates emboli in the left main and right upper lobe pulmonary arteries extending into bilateral anterior segmental arteries. (C) Right upper lobe ground-glass opacity with a reversed halo sign consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia. (D) Basilar consolidation compatible with COVID-19 lung involvement. Image courtesy of RSNA

Does a normal D-dimer level effectively rule out PE/DVT?

Yes. The value of D-dimer testing is the ability to rule out PE/DVT when the level is normal. Although the false-negative rate of D-dimer testing (i.e., PE/DVT is present but the result is normal) is unknown in this population, low rates of 1 – 2% using highly sensitive D-dimer assays have been reported in other high-risk populations. Therefore, a normal D-dimer level provides reasonable confidence that PE/DVT is not present and anticoagulation should continue at a prophylactic dose rather than empiric therapeutic dosing. In addition, radiological imaging is not necessary when the D-dimer level is normal in the context of low pre-test probability.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Diagram illustrating the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways leading to D-dimer formation. Endothelial injury activates the coagulation cascade, resulting in thrombin generation, fibrin formation, and subsequent plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis producing D-dimer, a key biomarker of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy

N.B.

- Normally plasma is negative for D-dimer.

- Qualitative: It is negative

- Quantitative : < 250 ng/mL or < 250 µg/L ( SI unit)

- Critical value >40 mg/L (40 µg/mL).

Increased D-dimer levels are seen in:

Primary and secondary fibrinolysis:

-

- DIC

- Thrombolytic therapy.

- Deep vein thrombosis.

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Arterial thromboembolism.

- myocardial infarction.

- Vaso-occlusive crises of sickle cell anemia.

- Infection.

- Renal Failure.

- pregnancy ( Especially postpartum period).

- Malignancy.

- Surgery.

False-Positive D-Dimer Test:

- This is seen in heparin therapy.

- The Rheumatoid factor can give false high values of FDP.

- This test is positive in patients after surgery or trauma.

- The false-positive test is seen in estrogen therapy and pregnancy.

If D-dimer levels change from normal to abnormal or rapidly increase on serial monitoring, is this indicative of PE/DVT?

An elevated D-dimer level does not confirm a diagnosis of PE/DVT in a patient with COVID-19 because the elevated D-dimer may result from many other causes. If possible, CTPA and/or bilateral CUS should be performed to investigate for PE/DVT. It is important to determine if there are any new clinical findings that indicate acute PE/DVT and if there are other causes of high D-dimer levels, such as secondary infection, myocardial infarction, renal failure, or coagulopathy. Published data have shown that the majority of patients with progressive, severe COVID-19 infection with acute lung injury/ARDS have very high D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, supportive of a hypercoagulable state from cytokine storm syndrome.

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Chest radiograph demonstrating rapidly progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in a 70-year-old female patient admitted with acute respiratory failure, fever, and dyspnoea. The patient was tachypnoeic with marked hypoxaemia (SpO₂ 85%, PaO₂/FiO₂ <250) and lymphopenia, reflecting severe COVID-19 disease

What are the risks and benefits of empiric therapeutic anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients?

COVID-19 infection is associated with high morbidity and mortality largely due to respiratory failure, with microvascular pulmonary thrombosis perhaps playing an important pathophysiological role. Having undiagnosed or untreated PE may worsen patient outcomes. Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin/LMWH may offer benefit and anti-viral mechanisms have been demonstrated for factor Xa inhibitors in animal studies. Consequently, the use of empiric therapeutic anticoagulation in certain COVID patients who do not have PE/DVT has been advocated. However, this remains controversial because the true incidence of PE/DVT in patients receiving pharmacological thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain and data to show improved outcomes with therapeutic anticoagulation are lacking. Current clinical trials addressing this question are underway. The risk of major bleeding is also heightened in those with risk factors for bleeding, such as older age, liver or renal impairment, and previous history of bleeding. Objective imaging to confirm a diagnosis of PE/DVT should, if possible, be done prior to starting therapeutic anticoagulation.

Are there any clinical scenarios in which empiric therapeutic anticoagulation would be considered in COVID-19 patients?

In cases where there are no contraindications for therapeutic anticoagulation and there is no possibility of performing imaging studies to diagnose PE or DVT, empiric anticoagulation has been proposed in the following scenarios:

- Intubated patients who develop sudden clinical and laboratory findings highly consistent with PE, such as desaturation, tachycardia, increased CVP or PA wedge pressure, or evidence of right heart strain on echocardiogram, especially when CXR and/or markers of inflammation are stable or improving.

- Patients with physical findings consistent with thrombosis, such as superficial thrombophlebitis, peripheral ischemia or cyanosis, thrombosis of dialysis filters, tubing or catheters, or retiform purpura (branching lesions caused by thrombosis in the dermal and subcutaneous vasculature).

- Patients with respiratory failure, particularly when D-dimer and/or fibrinogen levels are very high, in whom PE or microvascular thrombosis is highly suspected and other causes are not identified (e.g., ARDS, fluid overload).

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Bilateral retiform purpura involving both legs, representing a dermatological manifestation of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy and cutaneous microvascular thrombosis

If a patient is empirically started on anticoagulation for suspected PE, how long should they be anticoagulated? What if a later investigation shows no evidence of PE?

All patients with COVID-19 who are started on empiric therapeutic anticoagulation for presumed or documented PE should be given a minimum course of 3 months of the therapeutic regimen (provided the patient tolerates treatment without serious bleeding). Thrombus resolution can occur within a few days of effective anticoagulation, so negative results from delayed testing should not be interpreted as implying PE or DVT was not previously present. At 3 months, therapeutic anticoagulation can stop, provided the patient has recovered from COVID-19 and has no ongoing risk factors for thrombosis or other indications for anticoagulation (e.g. atrial fibrillation).

Protective Effect of Aspirin on Coronavirus Patients (PEAC):

COVID-19 has a high infection rate and mortality, and serious complications such as heart injury cannot be ignored. Cardiac dysfunction occurred in COVID-19 patients, but the law and mechanism of cardiac dysfunction remain unclear. The occurrence of progressive inflammatory factor storm and coagulation dysfunction in severe and fatal cases of novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) points out a new direction for reducing the incidence of severe and critically ill patients, shortening the length of duration in severe and critically ill patients and reducing the incidence of complications of cardiovascular diseases. Aspirin has the triple effects of inhibiting virus replication, anticoagulant, and anti-inflammatory, but it has not received attention in the treatment and prevention of NCP. Although Aspirin is not commonly used in the guidelines for the treatment of NCP, it was widely used in the treatment and prevention of a variety of human diseases after its first synthesis in 1898. Subsequently, aspirin has been confirmed to have an antiviral effect on multiple levels. Moreover, one study has confirmed that aspirin can inhibit virus replication by inhibiting prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in macrophages and upregulation of type I interferon production. Subsequently, pharmacological studies have found that aspirin is an anti-inflammatory and analgesic drug by inhibiting cox-oxidase (COX). Under certain conditions, the platelet is the main contributor of an innate immune response, studies have found that in the lung injury model in dynamic neutrophil and platelet aggregation.

In summary, the early use of aspirin (100mg a day) in covid-19 patients, which has the effects of inhibiting virus replication, anti-platelet aggregation, anti-inflammatory, and anti-lung injury, is expected to reduce the incidence of severe and critical patients, shorten the length of hospital duration and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular complications.

Dexamethasone in patients with severe Coronavirus:

Patients with severe COVID-19 can develop a systemic inflammatory response that can lead to lung injury and multisystem organ dysfunction. It has been proposed that the potent anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids might prevent or mitigate these deleterious effects. The Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, showed that the mortality rate was lower among patients who were randomized to receive dexamethasone than among those who received the standard of care. This benefit was observed in patients who required supplemental oxygen at enrollment. No benefit of dexamethasone was seen in patients who did not require supplemental oxygen at enrollment.

On the basis of the preliminary report from the RECOVERY trial, the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommends using dexamethasone 6 mg per day for up to 10 days or until hospital discharge, whichever comes first, for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients who are mechanically ventilated (AI) and in hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen but who are not mechanically ventilated (BI).

The Panel recommends against using dexamethasone for the treatment of COVID-19 in patients who do not require supplemental oxygen (AI).

If dexamethasone is not available, the Panel recommends using alternative glucocorticoids such as prednisone, methylprednisolone, or hydrocortisone (AIII).

Covid vaccines and blood clots:

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Commonly used COVID-19 vaccines, including mRNA and adenoviral vector vaccines, which play a central role in preventing severe disease and reducing COVID-19–related hematological and thrombotic complications

COVID-19 vaccines are medicines that prevent disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 by triggering an immune response.

Safe and effective vaccines for COVID-19 are needed because they protect individuals from becoming ill. This is particularly important for healthcare professionals and vulnerable populations such as older people, and those with underlying medical problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis, with devastating health, social and economic impacts. COVID-19 can cause severe disease and death. It has unknown long-term consequences in people of all ages, including in otherwise healthy people.

The European Commission confirmed it had granted conditional marketing authorization for the COVID-19 Vaccine BioNTech and Pfizer, the COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna, the COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca, and the COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen.

Misinformation about Covid vaccine risks and concerns over rare blood clots have had many searching the web for answers.

Public Health Wales: “Following reports of an extremely rare and specific blood clot after vaccination with the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) confirmed that this type of blood clot with low platelets are a possible side effect of the vaccine. However, they continue to advise that the benefits of vaccination with the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine continue to outweigh the risks of Covid-19 for the vast majority of adults.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended a pause in the use of the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen (J&J) COVID-19 vaccine while they investigated reports of a small number of women in the U.S. who developed a rare and severe type of blood clot within the two weeks following receipt of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Jo Jerrome, chief executive of Thrombosis UK: “Having a previous thrombosis or thrombophilia (sticky blood) is not a risk factor for developing the rare post-Covid-19 vaccine thrombosis and thrombocytopenia.”

Summary:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a systemic illness with profound effects on the blood and coagulation systems. Beyond respiratory involvement, SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a wide spectrum of hematological abnormalities, including lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer levels, and COVID-19–associated coagulopathy. Severe disease is characterized by endothelial injury, immune dysregulation, and a hypercoagulable state that predisposes to venous and arterial thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, microvascular thrombosis, and dermatological manifestations such as retiform purpura. Imaging findings, including CT pulmonary angiography and chest radiography, often correlate with laboratory markers of severity and adverse outcomes. Peripheral blood film abnormalities, ARDS, ICU admission, and markedly elevated D-dimer levels serve as important prognostic indicators. COVID-19 vaccination plays a crucial role in preventing severe disease and reducing hematological and thrombotic complications, with serious vaccine-related blood disorders remaining rare. Understanding the interaction between COVID-19 and the hematologic system is essential for early risk stratification, appropriate anticoagulation strategies, and optimal patient management.

Questions and Answers:

How does COVID-19 affect the blood and hematological system?

COVID-19 affects the blood through immune dysregulation, endothelial injury, and activation of coagulation pathways, leading to lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer levels, and a hypercoagulable state that increases the risk of thrombosis.

Why is D-dimer markedly elevated in patients with severe COVID-19?

D-dimer is elevated in COVID-19 due to increased fibrin formation and breakdown caused by widespread activation of coagulation and secondary fibrinolysis, reflecting ongoing thrombin generation rather than isolated clot breakdown.

What is COVID-19–associated coagulopathy?

COVID-19–associated coagulopathy is a prothrombotic condition characterized by elevated D-dimer, fibrinogen abnormalities, endothelial dysfunction, and a high risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism, distinct from classic disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Can COVID-19 cause pulmonary embolism?

Yes, COVID-19 significantly increases the risk of pulmonary embolism due to inflammation-driven hypercoagulability, endothelial injury, and stasis, particularly in hospitalized and critically ill patients with markedly elevated D-dimer levels.

What hematological abnormalities are seen on peripheral blood film in COVID-19?

Peripheral blood films in COVID-19 may show lymphopenia with reactive or atypical lymphocytes, reflecting immune activation, along with occasional platelet abnormalities in severe disease.

What is the significance of lymphopenia in COVID-19?

Lymphopenia is a common and important prognostic marker in COVID-19, associated with severe disease, progression to ARDS, ICU admission, and increased mortality.

How is acute respiratory distress syndrome related to hematological changes in COVID-19?

ARDS in COVID-19 is closely linked to systemic inflammation, immune-mediated lung injury, endothelial damage, and microvascular thrombosis, often occurring alongside lymphopenia and elevated coagulation markers.

What are the cutaneous signs of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy?

Cutaneous manifestations such as retiform purpura reflect underlying microvascular thrombosis and thrombotic vasculopathy, indicating severe COVID-19–related endothelial and coagulation dysfunction.

Does COVID-19 vaccination affect blood clotting?

COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduces the risk of severe infection and COVID-19–related coagulopathy, while serious vaccine-associated hematological complications are rare compared with the thrombotic risk of natural infection.

Why is anticoagulation important in hospitalized COVID-19 patients?

Anticoagulation is crucial in hospitalized COVID-19 patients to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism and microvascular thrombosis, guided by disease severity, D-dimer levels, and overall bleeding risk.

References:

Liji Thomas, MD. Does COVID-19 infect peripheral blood cells? News-Medical.

https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200519/Does-COVID-19-infect-peripheral-blood-cells.aspx

Moustafa A, Aziz RK. Traces of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the blood of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv preprint. 2020.

doi:10.1101/2020.05.10.20097055

Sally Robertson, BSc. Blood cell damage in COVID-19 may compromise oxygen transport. News-Medical.

https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200701/Blood-cell-damage-in-COVID-19-may-compromise-oxygen-transport.aspx

Spitalnik S, et al. Evidence for structural protein damage and membrane lipid remodeling in red blood cells from COVID-19 patients. bioRxiv. 2020.

doi:10.1101/2020.06.29.20142703

Yang M, Hon KL, Li K, Fok TF, Li CK. The effect of SARS coronavirus on the blood system: clinical findings and pathophysiologic hypotheses. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2003;11(3):217–221.

Chong VCL, Guan KG, Lim EB, Fan BE, Chan SSW, Ong KH, Kuperan P. Reactive lymphocytes in patients with COVID-19. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 2020.

doi:10.1111/ijlh.13307

Lee A, de Sancho M, Pai M, Huisman M, Moll S, Ageno W. COVID-19 and pulmonary embolism: frequently asked questions. American Society of Hematology.

https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-pulmonary-embolism

Kate Madden Yee. Almost 40% of CTPA exams find pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients. AuntMinnie.

https://www.auntminnie.com/index.aspx?sec=sup&sub=cto&pag=dis&ItemID=129487

Labpedia.net. D-dimer test (fragment D-dimer).

https://www.labpedia.net/d-dimer-test-fragment-d-dimer/

Lorente E. COVID-19: rapidly progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Radiopaedia.

https://radiopaedia.org/cases/covid-19-rapidly-progressive-acute-respiratory-distress-syndrome-ards

Bosch-Amate X, Giavedoni P, Podlipnik S, et al. Retiform purpura as a dermatological sign of COVID-19 coagulopathy. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2020;34(10):e548–e550.

doi:10.1111/jdv.16689

World Health Organization (WHO). Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation reports.

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov

ClinicalTrials.gov. Protective effect of aspirin on COVID-19 patients (PEAC). NCT04365309.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04365309

RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020.

PMID: 32678530

Catherine Evans. COVID vaccines and blood clots: your questions answered. BBC News.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-56764182

Maragakis L, Kelen G. Is the COVID-19 vaccine safe? Johns Hopkins Medicine.

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/is-the-covid19-vaccine-safe

Perera A, Chowdary P, Johnson J, et al. A ten-fold or greater increase in D-dimer predicts pulmonary embolism in COVID-19. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology. 2021;12:20406207211048364.

doi:10.1177/20406207211048364

National Institutes of Health (NIH). COVID-19 treatment guidelines: antithrombotic therapy.

https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antithrombotic-therapy

StatPearls Publishing. Coagulopathy in COVID-19. StatPearls.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570601/

Keywords:

coronavirus and blood, COVID-19 hematology, SARS-CoV-2 blood effects, hematologic complications of COVID-19, COVID-19 and thrombosis, COVID-19 associated coagulopathy, COVID-19 coagulation disorders, D-dimer COVID-19, elevated D-dimer coronavirus, pulmonary embolism COVID-19, COVID-19 hypercoagulable state, COVID-19 clotting disorders, red blood cell damage COVID-19, platelet abnormalities COVID-19, reactive lymphocytes COVID-19, lymphopenia coronavirus, leukopenia COVID-19, anemia in COVID-19, thromboinflammation SARS-CoV-2, microvascular thrombosis COVID-19, COVID-19 fibrinogen levels, cytokine storm and coagulopathy, endothelial dysfunction COVID-19, vascular injury SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 ARDS hematology, COVID-19 ICU complications, COVID-19 dermatological thrombosis, retiform purpura COVID-19, COVID-19 anticoagulation guidelines, thromboprophylaxis COVID-19, therapeutic anticoagulation COVID-19, aspirin in COVID-19, antithrombotic therapy COVID-19, COVID-19 pulmonary embolism imaging, COVID-19 CTPA findings, COVID-19 blood smear findings, COVID-19 vaccination and blood clots, VITT thrombosis, COVID-19 hematology review, hematology research COVID-19, Ask Hematologist COVID-19, Dr Moustafa Abdou hematology