Approach to Lymphocytosis

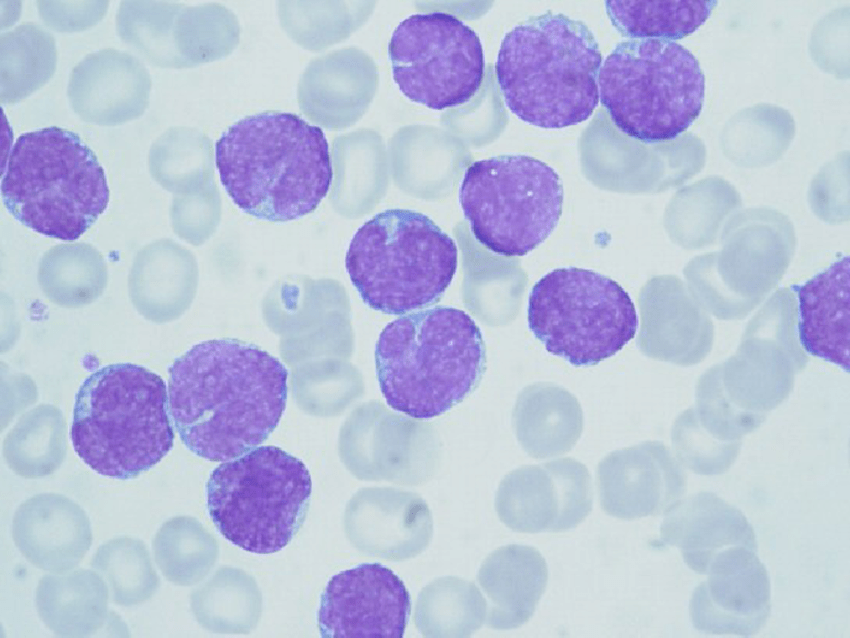

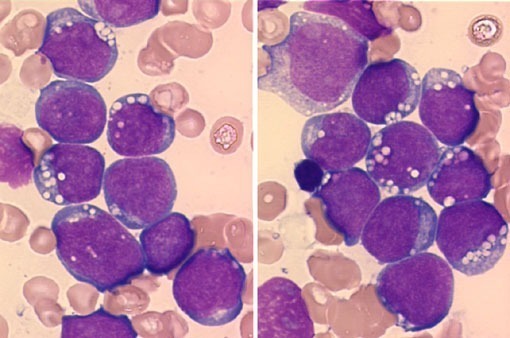

Peripheral blood smear showing a monomorphic population of mantle cell lymphoma cells with irregularly cleaved nuclei, condensed chromatin, and scant cytoplasm, consistent with a neoplastic lymphocytosis.

An effective approach to lymphocytosis is essential for accurate diagnosis and timely management in hematology. Lymphocytosis, defined as an increased lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood, can be reactive to infection, inflammatory states, or stress, but it may also signal underlying hematologic malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or other lymphoproliferative disorders. A structured evaluation helps clinicians differentiate between benign, self-limiting causes and conditions that require further investigation or referral.

Diagnostic Approach to Lymphocytosis:

Lymphocytes are white blood cells that serve primarily as the body’s adaptive immune system and provide humoral or cell-mediated immunity against a variety of bacterial, viral, or other pathogens. They are comprised mainly of T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells, and the body typically maintains the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in a range of fewer than 4,000 lymphocytes per uL. Elevation of the lymphocyte count above this level is most commonly due to a reactive lymphocytosis, the body’s normal response to an acute infection or inflammatory condition.

You can have a higher than normal lymphocyte count but have few, if any, symptoms. It usually occurs after an illness and is harmless and temporary. But it might represent something more serious, such as blood cancer or a chronic infection.

Your doctor might perform other tests to determine if your lymphocyte count is a cause for concern.

If your doctor determines that your lymphocyte count is high, the test result might be evidence of one of the following conditions:

- Infection (bacterial, viral, other)

- Cancer of the blood or lymphatic system

- An autoimmune disorder causing ongoing (chronic) inflammation

Specific causes of lymphocytosis include:

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

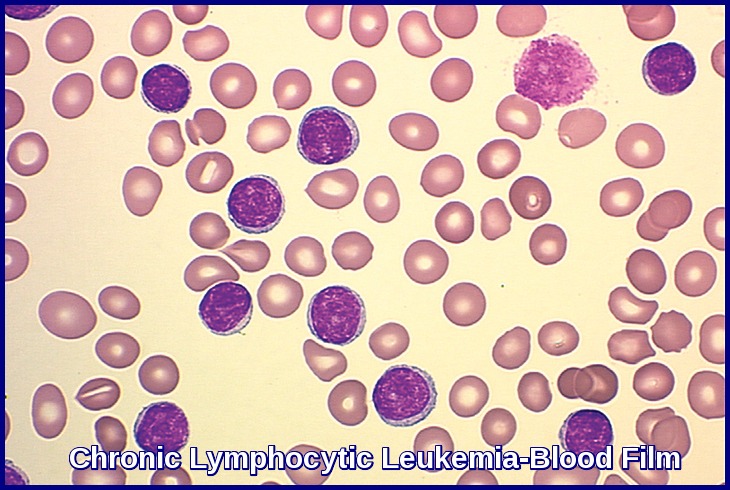

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Lymphoma

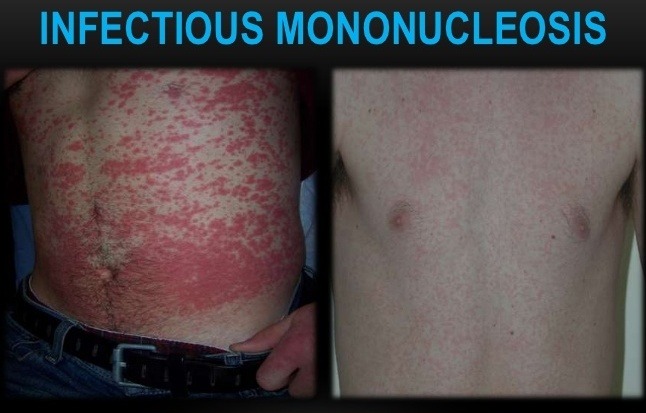

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- HIV/AIDS

- Other viral infections

- Syphilis

- Tuberculosis

- Whooping cough

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid)

Case:

A 71-year-old man with a history of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) last treated in 2007 with a rituximab and chlorambucil-based regimen presents with an increasing M protein of 4.1 g/dL (IgG κ). The laboratory findings were as follows: WBC, 7.4 × 109/L with 29 percent neutrophils, 66 percent lymphocytes, and 5 percent monocytes; RBC, 3.94 × 1012/L; hemoglobin, 11.0 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 83 fL; platelets, 91 × 109/L. The patient’s bone marrow was hypercellular (90%) with a marked lymphoid infiltrate present in nodular (paratrabecular and interstitial) and focal diffuse patterns involving 75 percent of bone marrow cellularity. Lymphocytes were small and round with condensed chromatin and occasional plasmacytoid lymphocytes were also observed. The karyotype of the bone marrow was 46,XY,add(9)(p24),der(11)del(11)(p13)del(11)(q23) in four cells with a sideline containing all of these abnormalities and +13 in two cells, and an unrelated clone showing 45,X,–Y in six cells, with 46,XY in seven cells. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) found a deletion of the 13q14.3 region and was negative for deletions of TP53, ATM, and LAMP1, and aneuploidy for chromosome 12.

Case response by Dr. Tracy I. George, MD, Professor of Pathology; Director of the Hematopathology Fellowship Program, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico:

Examining the Blood Smear

A slide review is appropriate in all patients with an unexplained lymphocytosis in order to confirm the automated cell counts or to perform a manual differential for leukocyte classification. In manually prepared blood smears, larger white blood cells tend to collect at the edges of the smear and in the feathered edge. Good practice for slide review requires assessments of all cell types (leukocytes, red blood cells [RBCs], and platelets) in both quantity and quality. It is not uncommon for fragile leukocytes such as in CLL, infectious mononucleosis, or acute leukemia to smudge on blood smears. In these situations, a few drops of albumin can be added to peripheral blood before preparing the blood smear. These “albumin smears” allow for proper identification of leukocytes and reduce the number of “smudge” or “basket” cells. However, the examination of RBCs and platelets should still be performed on the original blood smear because the albumin can affect platelet and erythrocyte morphology.

Peripheral blood smear in chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrating characteristic smudge cells due to lymphocyte fragility during smear preparation, along with small mature lymphocytes showing clumped chromatin.

Reactive Lymphocytosis

Separating a monomorphic lymphocytosis from a pleomorphic lymphocytosis can help distinguish a lymphoproliferative disorder from a reactive lymphocytosis, respectively. Most reactive lymphocytoses show a wide range of sizes and shapes in lymphocytes. The classic example of a pleomorphic lymphocytosis is infectious mononucleosis, where the lymphocytes range in size from small and round, to intermediate with abundant cytoplasm (reactive lymphocytes), to frank immunoblasts. It is this spectrum of morphology that points to a greater likelihood that a patient has a reactive lymphocytosis; younger age is also a helpful clue. The causes of a reactive lymphocytosis are extensive and include infections (viral, bacterial, and parasitic), autoimmune disease, vaccination, drug hypersensitivity, endocrine disorders, stress (trauma, cardiac, extreme exercise), smoking, and malignancy.

Peripheral blood smear showing atypical (reactive) lymphocytes with abundant basophilic cytoplasm, irregular cell borders scalloping around adjacent red cells, and enlarged nuclei, characteristic of infectious mononucleosis.

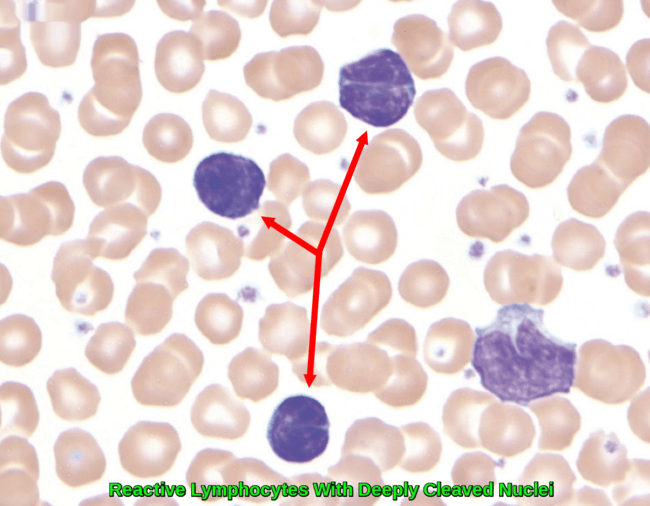

While most of these reactive lymphocytoses are pleomorphic, a few important exceptions are worth mentioning. The first is Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough. The lymphocytes of B. pertussis are small and deeply clefted with mature chromatin.

Peripheral blood smear from a child with Bordetella pertussis infection showing three small reactive lymphocytes with deeply cleaved nuclei and scant cytoplasm, in contrast to a monocyte in the lower right-hand corner. Reprinted with permission from I Pereira, TI George, and DA Arber.

As this is commonly seen in the pediatric and pregnant populations, the clinical correlation will readily separate this from lymphomas, which can show similar morphologic features (e.g. follicular lymphoma or Sézary syndrome).

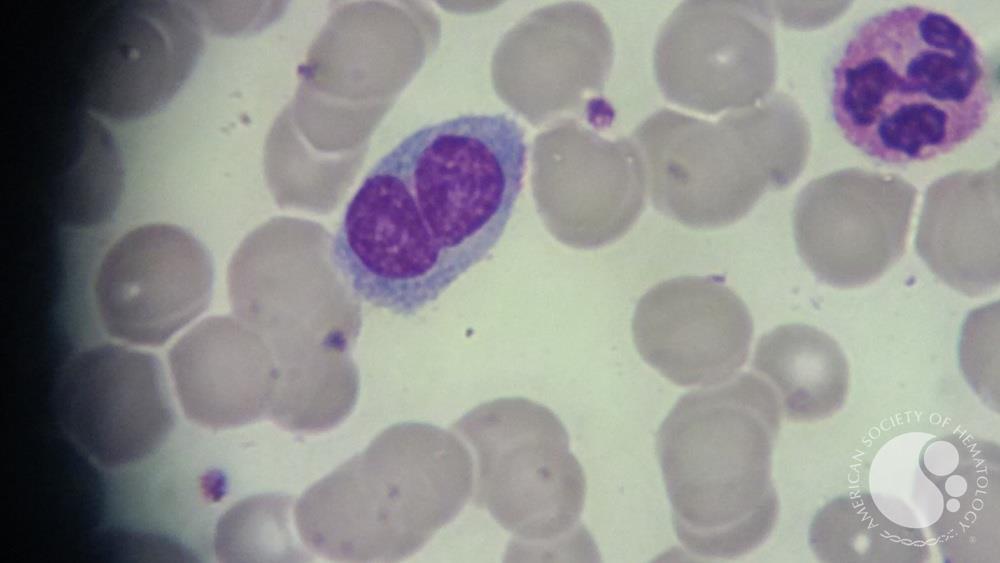

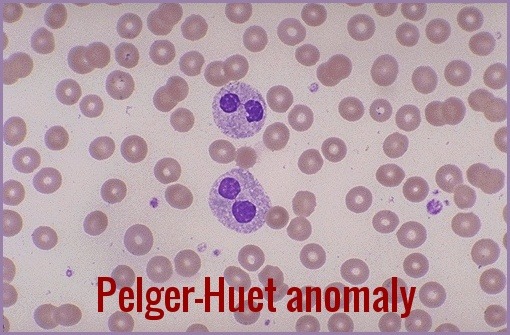

The second exception is polyclonal B-lymphocytosis, which typically shows lymphocytes with distinct nuclear clefts but will demonstrate a spectrum of morphologic changes including nuclear lobation and binucleate forms. This uncommon disorder is found in young to middle-aged female smokers with a high association with human leukocyte antigen DR7, and several genetic abnormalities have also been documented.

Peripheral blood smear showing a binucleated lymphocyte with abundant pale cytoplasm, a characteristic feature of polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, with surrounding red cells and a segmented neutrophil in the background.

The final exception is a large granular lymphocytosis. Increased numbers of large granular lymphocytes (reactive lymphocytes with scattered azurophilic granules) are commonly seen with viral infections, malignancy, after bone marrow transplantation, and following chemotherapy. These populations of large granular lymphocytes will wax and wane.

Peripheral blood smear showing a large granular lymphocyte characterized by abundant pale cytoplasm containing azurophilic granules and an eccentrically placed nucleus, a typical finding in large granular lymphocyte proliferations and reactive states.

However, the persistence of a large granular lymphocytosis with accompanying neutropenia and variable anemia should raise suspicion for large granular lymphocytic leukemia. This is typically T cell in origin, though a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of natural killer cells is also well described. Flow cytometry is recommended in these cases, followed by either T-cell clonality or KIR analysis, if involving T cells or natural killer cells, respectively.

Neoplastic Lymphocytosis

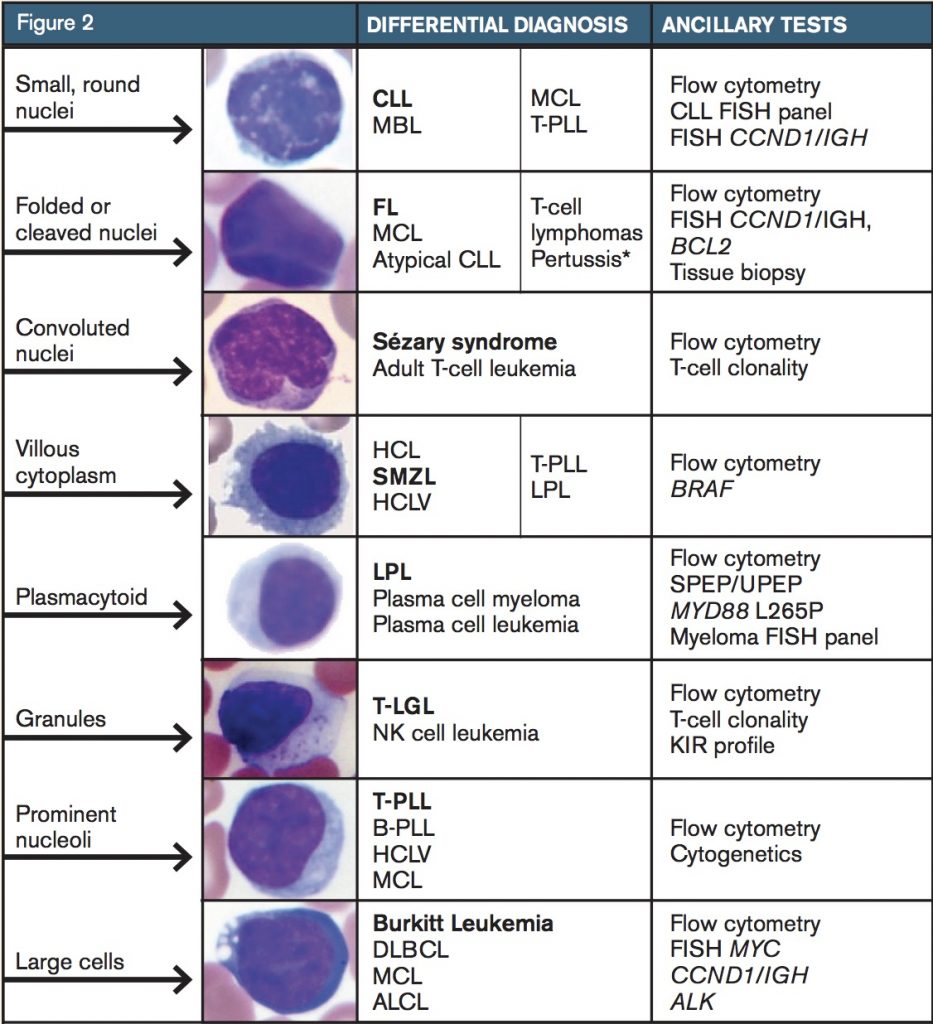

Lymphoma cells tend to be monomorphic in appearance. While a blood smear may contain a subset of lymphoma cells, these cells will resemble one another and stand out against a background of normal bland lymphocytes. While CLL is the most common leukemia in adults in the western world and is frequently seen in peripheral blood (or its monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis counterpart), peripheral blood involvement by bone marrow lymphoma is found in up to 30 percent of subjects in some studies. Lymphoma cells will show a wide variety of morphologic appearance, and this appearance raises a differential diagnosis as shown in Figure 2.

Composite figure illustrating key morphologic patterns of lymphocytes on peripheral blood smear—including small round nuclei, cleaved or folded nuclei, convoluted nuclei, villous cytoplasm, plasmacytoid features, cytoplasmic granules, prominent nucleoli, and large cell morphology—with corresponding differential diagnoses and recommended ancillary investigations such as flow cytometry, FISH, and molecular studies.

Further identification of the type of lymphoproliferative disorder typically proceeds with flow cytometry. While each laboratory has its own cocktail of antibodies used for flow cytometry, consensus guidelines have been published. While the results from flow cytometry narrow down one’s differential diagnosis to a shortlist, additional genetic or other ancillary studies are typically needed for confirmation, such as FISH for CCND1/IGH to evaluate for mantle cell lymphoma. Additionally, bone marrow biopsy or biopsy of another involved site is necessary for a final diagnosis.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis targeting deletion of chromosome 7q reveals complex chromosomal rearrangements in myeloid leukemia cell lines, highlighting the role of FISH in detecting cytogenetic abnormalities beyond isolated deletions.

A common question is when should flow cytometry be performed? Some studies have looked at this question in adults. In one study, the authors retrospectively reviewed flow cytometry results of 71 patients 50 years of age and older with an absolute lymphocyte count of 4 × 109/L or greater that had been called suspicious for a lymphoproliferative disorder after smear review by a pathologist. Using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, they found that an absolute lymphocyte count greater than 6.7 × 109/L for patients 50 to 67 years of age, and 4 × 109/L or greater for patients older than 67 years had a 95 percent sensitivity and 76 percent specificity for predicting an abnormal flow cytometry phenotype. A more recent retrospective single-center study examined 71 adults with newly detected lymphocytosis greater than 5 × 109/L in a consecutive three-month period and found that 6.8 × 109/L was the best cut-off value for predicting a lymphoproliferative disorder with ROC analysis (sensitivity 90%, specificity 59%). In my own practice, other triggers for flow cytometry include a persistent unexplained lymphocytosis or a morphology that does not correlate with the diagnosis.

Patient Follow-up

Review of the patient’s original diagnostic material confirmed that the atypical CLL diagnosis was given based on immunophenotypic expression of FMC7, in addition to the usual phenotype for CLL (CD20+, CD5+, CD23+). Morphology in the current blood and bone marrow showed lymphocytes and plasmacytoid cells and not the usual small round lymphocytes with coarsely clumped chromatin (“soccer balls”) of CLL; the plasmacytoid cells were not readily identified on the earlier bone marrow smears. The performed flow cytometry on the patient’s bone marrow identified a κ light chain–restricted B-cell population that expressed CD19, CD20, CD10, and CD23, and lacked expression of CD5 and CD200. Additionally, a κ light chain–restricted plasma cell population was identified.

Comparison of immunophenotypic markers in reactive lymphoid infiltrates versus chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), highlighting the differential expression of CD3, CD5, CD20, CD23, and CD43 that aids in distinguishing benign reactive processes from neoplastic CLL infiltration.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on the bone marrow clot section. Cyclin D1 and SOX-11 were negative in the B-cells, excluding the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma; SOX11 is a newer marker for mantle cell lymphoma that has been found to be expressed even in mantle cell lymphomas that lack overexpression of cyclin D1. LEF1 was negative, providing no support for a diagnosis of CLL. Markers of follicle center cell origin, BCL6 and LM02, were also negative, providing no support for a lymphoma of follicle center cell origin.

The cytogenetic karyotype, while abnormal, was not specific for any particular B-cell lymphoma; the lack of t(11;14) and t(14;18) argued against both mantle cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. Molecular testing for MYD88 L265P mutation was performed and was negative. DNA polymerase chain reaction analysis for immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) was performed on the 2007 bone marrow and on the current 2015 bone marrow. A clone was detected in both samples that was identical in amplicon size.

This case was presented at a multidisciplinary tumor board conference. While the immunophenotype of the lymphocytes switched from CD5 to CD10 expression, the IGH data supported that the same neoplastic clone was present in both the 2007 and current bone marrow. Thus, a low-grade B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation was found, raising a differential diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, versus a marginal zone lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation. While the lack of a MYD88 L265P mutation argues against lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, my colleagues have found this to be 96 percent sensitive for a diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma in a study of 317 cases of low-grade B-cell lymphomas. A diagnosis of atypical CLL seemed less likely, as the lymphocytes lacked LEF1 expression – a marker identified based on gene expression profiling data that has been described as nearly 100 percent sensitive and specific for CLL. The lymphocytes also lacked expression of CD200 by flow cytometry, another marker overexpressed in CLL as well as lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, though few cases of the latter were tested. While the patient lacked splenomegaly, a diagnosis of marginal zone lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation was considered. The patient is scheduled to receive ibrutinib.

Questions and Answers:

Q: What is lymphocytosis and when should it raise concern?

A: Lymphocytosis refers to an elevated absolute lymphocyte count, generally above ~4 ×10⁹/L in adults. While frequently reactive due to infections or stress, persistent elevations or significantly high counts (for example >6.7 ×10⁹/L in older adults) should prompt evaluation for a possible lymphoproliferative disorder.

Q: What are the most common reactive causes of lymphocytosis?

A: Common reactive causes include viral infections such as EBV and CMV, certain bacterial infections like pertussis, autoimmune disorders, endocrine abnormalities, medications, smoking, and physiological stress responses including trauma or recent surgery.

Q: How can clinicians differentiate reactive from malignant lymphocytosis?

A: Distinguishing features include variability versus uniformity on blood smear morphology, presence or absence of a clear reactive trigger, duration of the lymphocytosis, and whether flow cytometry demonstrates a polyclonal or monoclonal lymphocyte population.

Q: What is the role of flow cytometry in evaluating unexplained lymphocytosis?

A: Flow cytometry is essential when lymphocytosis is persistent, unexplained, or above recognized cut-offs. It identifies monoclonal B-cell, T-cell, or NK-cell populations and helps diagnose conditions such as CLL, MBL, T-cell LPDs, and NK-cell proliferations.

Q: What initial investigations should be performed when lymphocytosis is detected?

A: The first steps include a full blood count with manual differential, a peripheral smear to assess morphology and validate automated counts, clinical context review, and—when indicated—immunophenotyping to determine clonality.

Q: When should a patient with lymphocytosis be referred to hematology?

A: Referral is recommended when lymphocytosis persists without explanation, morphology or immunophenotype appears suspicious, lymphocyte counts exceed established risk thresholds, or the patient has associated clinical features such as cytopenias, lymphadenopathy, or organomegaly.

Q: What uncommon causes of lymphocytosis should be considered?

A: Important but less common causes include large granular lymphocyte leukemia, persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, and certain lymphomas with peripheral blood involvement. These entities often present with characteristic clinical or morphological features requiring specialist input.

Q: What lymphocyte count thresholds are considered high risk for malignancy?

A: While no absolute cutoff guarantees malignancy, lymphocyte counts persistently above 10 ×10⁹/L, rapidly rising counts, or extreme lymphocytosis (>30–50 ×10⁹/L) are strongly suggestive of an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder and warrant urgent hematology assessment.

Q: Does lymphocytosis always require bone marrow examination?

A: No. Most cases can be adequately evaluated using peripheral blood morphology and flow cytometry. Bone marrow examination is reserved for cases with diagnostic uncertainty, unexplained cytopenias, suspected marrow infiltration, or when required for staging or prognostic assessment.

Q: How long can reactive lymphocytosis persist after infection?

A: Reactive lymphocytosis may persist for several weeks following acute infection, particularly after EBV or CMV. Persistence beyond 3 months without a clear cause should prompt reassessment and consideration of clonal lymphocytosis.

Q: What is monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) and how is it related to CLL?

A: MBL is defined by the presence of a small monoclonal B-cell population in the blood with lymphocyte counts below the diagnostic threshold for CLL and no clinical features of malignancy. It is a precursor condition with a low annual risk of progression to CLL.

Q: Can lymphocytosis be caused by smoking?

A: Yes. Chronic smoking is a recognized cause of persistent mild lymphocytosis and is particularly associated with persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, most often seen in middle-aged female smokers.

Q: What blood film features are particularly suggestive of malignant lymphocytosis?

A: Features raising concern include a monomorphic lymphocyte population, cleaved or convoluted nuclei, prominent nucleoli, cytoplasmic villi, granules suggestive of LGL disorders, or circulating blast-like cells, especially when persistent.

Q: Is lymphocytosis common in children and does it differ from adults?

A: Lymphocytosis is more common and often physiological in children, particularly in early childhood. In adults, especially older patients, persistent lymphocytosis is more likely to reflect an underlying clonal process and requires careful evaluation.

Q: What ancillary tests may be required beyond flow cytometry?

A: Depending on findings, additional tests may include FISH for recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities (e.g. del(13q), t(11;14)), molecular studies (e.g. MYD88, BRAF), viral serology, imaging for lymphadenopathy or organomegaly, and serum protein electrophoresis.

Q: Can lymphocytosis occur with normal total white cell count?

A: Yes. Relative lymphocytosis can occur when the absolute lymphocyte count is normal but lymphocytes comprise a higher proportion of leukocytes, often due to neutropenia or recovery from marrow suppression.

References:

George, T. I. Diagnostic Approach to Lymphocytosis. American Society of Hematology – The Hematologist. Available at: https://www.hematology.org/thehematologist/ask/4507.aspx

Lazarchick, J. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Thrombocytopenia. ASH Image Bank. Available at: http://imagebank.hematology.org/image/1359/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-thrombocytopenia–2

Mayo Clinic Staff. Lymphocytosis (High Lymphocyte Count) – Causes. Mayo Clinic. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/symptoms/lymphocytosis/basics/causes/sym-20050660

Brown, J. R.; Davids, M. S. Approach to Lymphocytosis. Cancer Therapy Advisor. Available at: https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/hematology/approach-to-lymphocytosis-2/

Mossafa, H.; Tapia, S.; Flandrin, G.; et al. Chromosomal Instability and ATR Amplification in Patients with Persistent Polyclonal B-Cell Lymphocytosis (PPBL). Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2004;45:1401–1406.

George, T. I. Malignant or Benign Leukocytosis. Hematology – American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2012;2012:475–484.

Dhodapkar, M. V.; Li, C. Y.; Lust, J. A.; et al. Clinical Spectrum of Clonal Proliferations of T-Large Granular Lymphocytes: A T-Cell Clonopathy of Undetermined Significance. Blood. 1994;84:1620–1627.

Arber, D. A.; George, T. I. Bone Marrow Biopsy Involvement by Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Frequency, Patterns, Blood Involvement, and Discordance in 450 Cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2005;29:1549–1557.

Chabot-Richards, D. S.; George, T. I. Leukocytosis: A Review. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 2014;36:279–288.

Béné, M. C.; Nebe, T.; Bettelheim, P.; et al. Immunophenotyping of Acute Leukemia and Lymphoproliferative Disorders: Consensus Recommendations of the European LeukemiaNet Work Package 10. Leukemia. 2011;25:567–574.

Andrews, J. M.; Cruser, D. L.; Myers, J. B.; et al. Use of Blood Smear Morphology, Age, and Absolute Lymphocyte Count as Predictors of Abnormal Lymphocytosis Diagnosed by Flow Cytometry. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2008;49:1731–1737.

Sun, P.; Kowalski, E. M.; Cheng, C. K.; et al. Predictive Significance of Absolute Lymphocyte Count and Morphology in Newly Detected Adult Peripheral Blood Lymphocytosis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2014;67:1062–1066.

Soldini, D.; Valera, A.; Solé, C.; et al. SOX11 Expression in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Evaluation Using Novel Monoclonal Antibodies. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2014;38:86–93.

Insuasti-Beltran, G.; Gale, J. M.; Wilson, C. S.; et al. MYD88 L265P Mutation in the Classification of Low-Grade B-Cell Lymphomas. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2015;139:1035–1041.

Tandon, B.; Peterson, L.; Gao, J.; et al. Nuclear Overexpression of LEF1 Identifies CLL/SLL Among Small B-Cell Lymphomas. Modern Pathology. 2011;24:1433–1443.

Challagundla, P.; Medeiros, L. J.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; et al. Differential CD200 Expression in B-Cell Neoplasms Assists in Diagnosis and Subclassification. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2014;142:837–844.

Maslak, P.; McKenzie, S. Infectious Mononucleosis – ASH Image Bank. American Society of Hematology. https://imagebank.hematology.org/image/1867/infectious-mononucleosis–1

Kamel, Y. M.; et al. FISH Assays for del(7q) Reveal Complex Cytogenetic Rearrangements in Myeloid Leukemia Cell Lines. 2014. (Retained for relevance to lymphocytosis-related cytogenetics.)

Creative Bioarray. Multicolor FISH (mFISH) Analysis – Overview of Cytogenetic Applications. https://www.creative-bioarray.com/services/multicolor-fish-m-fish-analysis.htm

Keywords:

approach to lymphocytosis, evaluation of lymphocytosis, causes of lymphocytosis, absolute lymphocyte count significance, high lymphocyte count in adults, high lymphocyte count in children, persistent lymphocytosis causes, reactive lymphocytosis, malignant lymphocytosis, lymphocytosis differential diagnosis, lymphocytosis work-up, lymphocytosis diagnostic algorithm, lymphocytosis hematology investigation, lymphocytosis blood film review, lymphocytosis morphology findings, flow cytometry for lymphocytosis, lymphoproliferative disorders evaluation, monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia early signs, lymphocytosis referral criteria, when to refer lymphocytosis, lymphocytosis management guidelines, viral infection lymphocytosis, EBV lymphocytosis features, CMV lymphocytosis features, pertussis lymphocytosis, autoimmune causes of lymphocytosis, smoking-related lymphocytosis, stress-induced lymphocytosis, lymphocytosis red flags, lymphocytosis prognosis indicators, abnormal lymphocyte morphology, lymphocytosis smear interpretation, lymphocytosis threshold for flow cytometry, approach to high ALC, Ask Hematologist, Dr Moustafa Abdou

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now

Thanks, sir .very interesting information

Hi Reda,

Thanks for your comment.

BW,

Hey BW,

My original comment was flagged as spam so I’ll be more concise in this next one. Would you find 5% Large granular lymphocytes significant in a patient receiving treatment for essential thrombocythemia? NRBCs and elevated IGs were also noted, RBC count decreased, PLT count is normal w/ large platelets noted.

Hi Troy,

Thank you for your comment.

No, 5% LGLs in the peripheral blood is normal.

LGLs comprise 10 to 15 percent of normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The absolute number of LGLs in the peripheral blood of normal subjects is 0.2-0.4×109/L.

BW,

If someone was post splenectomy 9 years and currently has chronic absolute lymphocytosis of 4956-5000+ range and 59% lymphocytes for past year is this indicative of a malignancy or is this normal for post splenectomy state?

Hi Jessica,

Thanks for your comment.

Mild lymphocytosis could be reactive but if persistent I would suggest blood flow cytometry to out rule possible underlying chronic lymphoproliferative disorder?Monoclonal B Lymphocytosis/CLL.

BW,

Hi, thanks for your answers.

Please tell me how calculate segmented neutrophils precent and what normal range

Hi Bahman,

Thanks for your comment.

Neutrophils are counted as part of the Complete Blood Count (CBC).

If you have the absolute neutrophil count e.g. 2.5 and your total white cell count is 5.0 then your neutrophil percentage is 50%, and so on.

Normal range is:

Segmented neutrophils 2,500-6,000 40-60%

BW,

Hi There,

What does this mean: An abnormal population of lymphoid cells (50% of total cellular events) positive for CD5, CD19, CD20 and CD23, negative for CD10 and FMC7, showing dim kappa light chain specificity is present. T-cells are antigenically normal.

Hi Betty,

Thank you for your comment.

If this is your blood flow cytometry report it would fit with a lymphoproliferative disorder e.g. CLL.

You should discuss it with your hematologist.

BW,

Have just received 9 pages of blood tests results. Until I read your well thought out and clearly written article I didn’t have a clue how to start absorbing the information.

Thank you for taking the time to simplify the complexities of blood cells.

Suzanne November 17, 2022

Hi Suzanne,

Many thanks for your comment.

Pleased that you found this article helpful.

BW,

Hi there,

My lymphocyte count has continuously come back between 4.5-4.9 xE9/L for the past two years. All other cell counts are within normal range therfore doctor does not want to recommend me to hematologist (I’ve seen 2!) is this normal?

Hi Erika,

Thank you for reaching out to me at AskHematologist.com.

If you are not a smoker and do not suffer from a persistent infection or autoimmune disorder, and are not on steroids, you should consider doing a blood flow cytometry to rule out possible Monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL).

Best regards,

Dr M Abdou

Thank you so much for your interesting,clear article..Is there a count limit for extreme reactive lymphocytosis(lymphocyte leukomoid reaction)?

Hi Sabry,

Thank you for reaching out.

There isn’t a specific count limit for extreme reactive lymphocytosis, which can occur in response to an infection, inflammation, or certain medications. However, if the lymphocyte count is exceptionally high or persists for more than a few weeks, I would recommend conducting a blood film and a blood flow cytometry to rule out malignancy.

Best regards,

Dr. M Abdou

Much obliged 🙏🙏🙏