Amyloidosis

Illustration showing systemic amyloidosis with amyloid protein deposition affecting multiple organs including the heart, kidneys, brain, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreas.

Amyloidosis refers to a group of rare but serious disorders characterized by the abnormal deposition of amyloid proteins in organs and tissues throughout the body. These insoluble misfolded proteins, produced in the bone marrow, accumulate in vital organs such as the heart, kidneys, liver, and nervous system, impairing their normal function. The ICD-10 code for amyloidosis is E85.9.

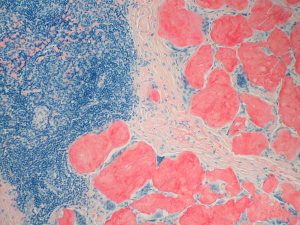

First described by Matthias Schleiden in 1834 and later named by Rudolph Virchow in 1854, amyloid was identified as a waxy, starch-like material that stains characteristically with Congo red dye, showing pink coloration under standard light and apple-green birefringence under polarized light.

Although all amyloid types appear similar under light microscopy, specialized laboratory tests such as immunohistochemistry, mass spectrometry, or genetic analysis are crucial for determining the amyloid subtype (e.g., AL, AA, or ATTR amyloidosis)—an essential step for accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and tailored therapy.

Congo red–stained histological section demonstrating amyloid deposition in lymph node tissue in systemic amyloidosis.

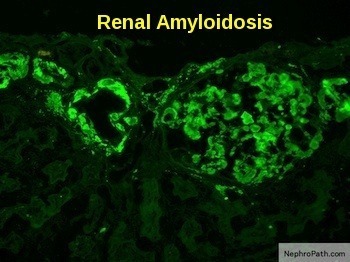

Renal amyloidosis showing apple-green birefringence of amyloid deposits under polarized light with positive lambda light-chain immunostaining in a glomerulus.

Amyloidosis can affect multiple organs, and the pattern of involvement varies depending on the type of amyloid protein involved. The disease most commonly targets the heart, kidneys, liver, spleen, nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract, where progressive amyloid deposition disrupts normal organ function. Without timely diagnosis and treatment, systemic amyloidosis can lead to life-threatening organ failure, particularly in cardiac and renal forms. Although there is no definitive cure for amyloidosis, modern therapies can reduce amyloid production, stabilize existing deposits, and alleviate symptoms, thereby improving organ function and quality of life. Early recognition and targeted management are essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with amyloidosis.

Types of Amyloidosis:

AL Amyloidosis (immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis):

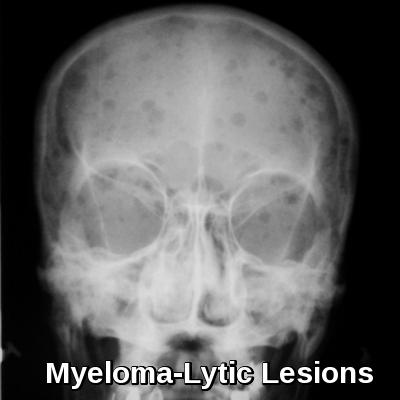

The most common type of amyloidosis and used to be called primary amyloidosis results when light chains are produced in excess by clonal or frankly malignant plasma cells. It occurs in 10-15% of patients with full-blown multiple myeloma but can also be seen when the affected patient has less than 10% bone marrow plasma cells, the quantity typically required to make a diagnosis of myeloma. Light-chain amyloidosis may also arise in association with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. It is a relatively rare disease with an incidence of 5.1-12.8 per million person-years and only 1,275-3,200 new cases being diagnosed in the United States annually. The male-to-female ratio is 3:2. Although healthy individuals have a preponderance of kappa free light chains (K/λ) = 2:1), the reverse is true in most patients with primary amyloidosis, as excess lambda light chains have a greater propensity to be amyloidogenic.

AA amyloidosis:

Previously known as secondary amyloidosis, this condition is the result of another chronic infectious or inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis. It mostly affects the kidneys, but it can also involve the digestive tract, liver, and heart. AA means the amyloid type A protein causes this type.

Dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA):

This is more common in older adults and people who have been on dialysis for more than 5 years. This form of amyloidosis is caused by deposits of beta-2 microglobulin that build up in the blood. Deposits can build up in many different tissues, but it most commonly affects bones, joints, and tendons.

Familial, or hereditary, amyloidosis:

This is a rare form passed down through families. It often affects the liver, nerves, heart, and kidneys. Many genetic defects are linked to a higher chance of amyloid disease. For example, an abnormal protein like transthyretin (TTR) can be the cause.

Age-related (senile) systemic amyloidosis:

This is caused by deposits of normal TTR in the heart and other tissues. It happens most commonly in older men.

Organ-specific amyloidosis:

This causes deposits of amyloid protein in single organs, including the skin (cutaneous amyloidosis). Though some types of amyloid deposits have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease, the brain is rarely affected by amyloidosis that happens throughout the body.

Amyloidosis symptoms and signs:

Amyloidosis presents in a variety of ways and can make diagnosis difficult. It is helpful to separate the presentation into two patterns: localized and systemic. Localized amyloidoses are confined to one site and are generally non-lethal. Skin is a common site of deposition and can manifest as asymptomatic plaques, fissures or nodules.

Clinical image of cutaneous amyloidosis showing localized hyperpigmented skin changes resulting from amyloid deposition in the dermis.

Systemic amyloidosis implies the involvement of visceral organ(s) or multiple tissues. Patients may present with symptoms limited to one organ or with multiorgan failure. The kidney is the most common organ involved in AL, AA and most forms of hereditary amyloidosis except ATTR. Proteinuria is present in 73% of the AL amyloidosis patients with 30% exhibiting nephrotic syndrome. Renal insufficiency is noted in nearly half of the patients which is usually associated with proteinuria. Renal involvement is nearly

universal (97%) in AA amyloidosis.

Clinical photograph demonstrating severe bilateral lower limb edema, a characteristic feature of nephrotic syndrome.

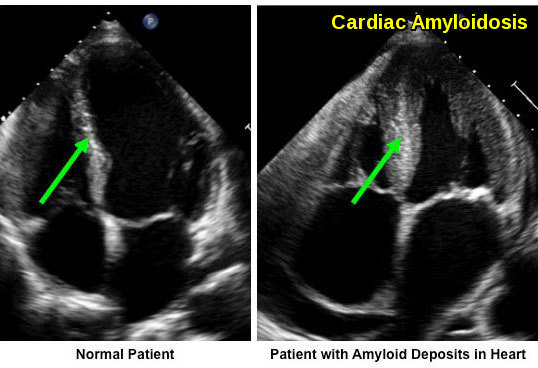

The heart is the next most common organ involved in AL amyloidosis with abnormal echocardiographic findings noted in 65% of patients. Presentation varies from asymptomatic to a subtle decreased in exercise capacity to fatigue, dyspnea and lower extremity edema to angina, syncope, ascites, and anasarca which are associated with more advanced disease. Overt heart failure can be seen in 24%. Low voltage on electrocardiogram (ECG) and concentric thickened ventricles on echocardiogram are classic signs of cardiac involvement by amyloidosis. Cardiac involvement, on the other hand, is rare in AA amyloidosis occurring in only 1% of patients.

Amyloid fibril deposition within the myocardium leads to increased ventricular wall thickness. The patient with cardiac amyloidosis shows marked myocardial thickening compared with the normal heart.

The nervous system is a prominent feature in some forms of amyloidosis and can involve the central, peripheral nerves or both. Peripheral nerve involvement can present with bilateral distal progressive paraesthesia or carpel tunnel syndrome. Autonomic nervous

system involvement is characterized by syncope, erectile dysfunction, gastroparesis, and diarrhea.

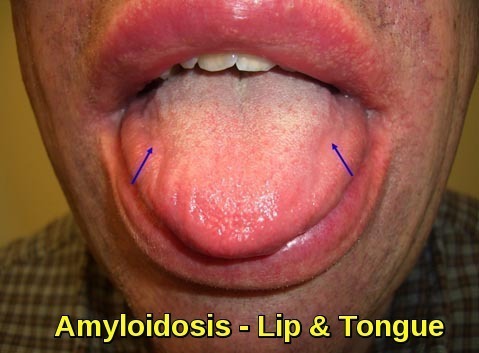

Gastrointestinal presentation is not common and usually present with macroglossia, nausea, vomiting, and pseudoobstruction which accounts for < 10% of AL amyloidosis cases. Hepatomegaly is present in 24% of AL amyloidosis patients but only 9% of AA

amyloidosis. Bruising is common and often occurs after minor trauma or procedure especially around the eyes.

Clinical image demonstrating macroglossia with lip involvement due to amyloid deposition, a characteristic feature of systemic amyloidosis.

Symptoms common to most types of amyloid include fatigue and weight loss which are reported by over half of the patients. Weight loss, however, is unreliable in patients with nephrotic syndrome since many will gain weight as their edema worsens.

In summary, symptoms in patients with amyloidosis result from abnormal functioning of the particular organs involved. There might be no symptoms until the disease is relatively advanced. The heart, kidneys, liver, bowels, skin, nerves, joints, and lungs can be affected. As a result, symptoms and signs are vague and can include fatigue, shortness of breath, weight loss, lack of appetite, numbness, tingling, carpal tunnel syndrome, weakness, hearing loss, enlarged tongue, bruising, and swelling of hands and feet. Amyloidosis in these organs leads to cardiomyopathy, heart failure, peripheral neuropathy, arthritis, malabsorption, diarrhea, and liver damage and failure. Amyloidosis affecting the kidney leads to “nephrotic syndrome” which is characterized by severe loss of protein in the urine and swelling of the extremities.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of amyloidosis is often delayed because the symptoms are so varied. Patients often get treated for heart or kidney failure for months before the underlying root of the problem is identified, typically by a biopsy.

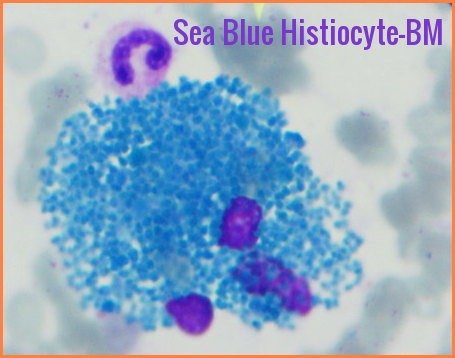

Blood and urine tests may reveal an abnormal immunoglobulin protein in the body in those patients with AL Amyloidosis, but the only way to diagnose amyloidosis for certain is to take a sample of tissue for analysis under a microscope. The tissue is often taken from the fat around the abdomen which can be done on an outpatient basis in patients suspected as having the condition. This fat aspiration test will show a confirmatory positive result in 80% of patients with amyloidosis. Alternatively, a biopsy of the organ that is not functioning properly such as the heart, kidney or nerve can more reliably identify the condition but can be more cumbersome to obtain. This method of identification is becoming more common in our experience and often leads to the diagnosis in patients not suspected of the condition beforehand. A biopsy of the bone marrow is another useful method of detection and is critical to perform in patients suspected as having AL amyloidosis since it can identify and quantify the bone marrow lymphocytes or plasma cells which typically live there and are causing the problem. All of the above samples are stained with a dye called Congo Red that reacts with amyloid which can then be identified under a microscope.

It is critical to characterize the nature of the amyloid protein that is present since each of the various types of amyloidosis (such as AL, ATTR, or AA) is treated quite differently. Mass spectroscopy is a special technique that can be used on tissue samples to reliably determine the type of protein present. Blood samples can be used to sequence the various genes such as transthyretin or fibrinogen to determine if a predisposing gene variant exists. For patients with AL Amyloidosis, the free light chain assay is extremely useful to monitor the response to treatment. Patients suspected of heart involvement can get a cardiac MRI which can typically demonstrate findings suggestive of amyloidosis in those patients afflicted.

Treatment of Amyloidosis:

Treatment of amyloidosis is given to improve symptoms and extend life. Treatment can limit further production of amyloid proteins and, in some instances, promote the breakdown of amyloid proteins in affected organs. The type of treatment required varies depending on the type of amyloidosis and the patient’s symptoms.

With secondary amyloid, the main goal of therapy is to treat the underlying condition — for example, taking an anti-inflammatory medication for rheumatoid arthritis or antibiotics for an infection.

In hereditary amyloid, liver transplantation has been the most effective therapy. The new liver does not produce the abnormal amyloid proteins and consequently, the disease improves. Investigational drugs are also being evaluated to try and prevent this type of amyloid protein from depositing in organs.

For primary amyloid, treatments include the same agents used to treat multiple myeloma, such as chemotherapy, corticosteroids, immunomodulatory drugs (lenalidomide or thalidomide) and/or bortezomib (Velcade). These treatments slow organ deterioration and some have been shown to prolong life, but none provide a cure.

Because primary amyloid is such a difficult disease to treat and survival is limited, researchers have begun to investigate the use of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation as a means of prolonging survival. The initial results with autologous stem cell transplantation are encouraging.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

Patients with primary amyloid undergo an extensive workup to evaluate organ function and the effects that amyloidosis has had on the body. Those with adequate heart, liver and lung function are encouraged to proceed to autologous stem cell transplantation.

High-dose melphalan chemotherapy is administered over one day. Then the patient’s own stem cells (bone marrow) are re-administered two to three days later. An additional three to four weeks are spent in the hospital awaiting recovery and growth of the bone marrow.

The hope is that this therapy will delay the progression of the disease, and in some cases, improve symptoms through the removal of the abnormal proteins from the organs. However, this therapy is not a cure, and amyloidosis will return in everyone. That said, we have had patients who have been successfully treated with stem cell transplantation and when their disease progressed, have been able to receive another stem cell transplant.

Several new investigational agents are being evaluated in the treatment of multiple myeloma, another plasma cell disorder. The hope is that some of these agents also may be effective in treating amyloidosis. For patients who are not candidates for stem cell transplantation, these agents may prove to be the best available treatment.

Patients with hereditary amyloid should be referred to a Liver Transplant Clinic for evaluation.

Summary:

Amyloidosis is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by extracellular deposition of misfolded amyloid fibrils in tissues and organs, leading to progressive organ dysfunction. These insoluble protein aggregates disrupt normal tissue architecture and function, with clinical manifestations determined by the type of amyloid protein and the organs involved. Major subtypes include AL (light-chain) amyloidosis, commonly associated with plasma cell dyscrasias; AA amyloidosis, secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions; ATTR amyloidosis, both hereditary and wild-type; dialysis-related amyloidosis; and localized organ-specific forms.

Systemic amyloidosis frequently affects the kidneys, heart, nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and soft tissues. Renal involvement often presents with proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome, while cardiac amyloidosis leads to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and characteristic imaging findings on echocardiography and cardiac MRI. Other hallmark features include peripheral and autonomic neuropathy, hepatosplenomegaly, macroglossia, cutaneous manifestations, and unexplained weight loss.

Diagnosis of amyloidosis relies on tissue biopsy demonstrating Congo red–positive amyloid deposits with apple-green birefringence under polarized light, followed by accurate amyloid typing using immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or mass spectrometry. Identifying the amyloid subtype is essential, as management and prognosis vary significantly between forms. Treatment strategies focus on controlling the underlying disease process, reducing amyloid production, and managing organ-specific complications.

Early recognition of amyloidosis is critical, as delayed diagnosis is common and is associated with poorer outcomes. A high index of suspicion is required in patients with multisystem involvement, unexplained cardiomyopathy, nephrotic syndrome, or plasma cell disorders. Advances in diagnostic techniques and targeted therapies have significantly improved outcomes, particularly when amyloidosis is diagnosed at an early stage.

Questions and Answers:

What is amyloidosis?

Amyloidosis is a group of disorders caused by extracellular deposition of misfolded amyloid proteins in tissues and organs, leading to progressive organ dysfunction.

What are amyloid proteins made of?

Amyloid proteins are abnormally folded fibrillar proteins derived from different precursor proteins, such as immunoglobulin light chains, serum amyloid A, or transthyretin.

What are the main types of amyloidosis?

The main types include AL (light-chain) amyloidosis, AA amyloidosis, ATTR amyloidosis (hereditary and wild-type), dialysis-related amyloidosis, and localized organ-specific amyloidosis.

Which organs are most commonly affected by amyloidosis?

Amyloidosis most commonly affects the kidneys, heart, peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal tract, liver, skin, and soft tissues.

How does amyloidosis affect the kidneys?

Renal amyloidosis causes amyloid deposition in the glomeruli, leading to proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, edema, and progressive decline in kidney function.

What are the cardiac manifestations of amyloidosis?

Cardiac amyloidosis results in restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, arrhythmias, and increased ventricular wall thickness due to myocardial infiltration.

Why does the heart wall appear thickened in cardiac amyloidosis?

The apparent wall thickening is caused by amyloid infiltration of the myocardium rather than true myocardial hypertrophy.

How is cardiac amyloidosis diagnosed on imaging?

Echocardiography shows increased wall thickness and diastolic dysfunction, while cardiac MRI demonstrates characteristic late gadolinium enhancement patterns.

What is late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac amyloidosis?

Late gadolinium enhancement reflects diffuse myocardial amyloid infiltration and typically shows circumferential subendocardial or septal enhancement patterns on cardiac MRI.

What is the significance of Congo red staining in amyloidosis?

Congo red staining confirms amyloid deposition by demonstrating apple-green birefringence under polarized light, which is diagnostic of amyloidosis.

What does apple-green birefringence indicate?

Apple-green birefringence under polarized light confirms the presence of amyloid fibrils within tissue samples.

Is lymph node involvement common in amyloidosis?

Lymph node involvement is uncommon and usually reflects systemic amyloidosis rather than a primary or diagnostic feature.

What is AL amyloidosis?

AL amyloidosis is caused by deposition of immunoglobulin light chains and is most commonly associated with plasma cell disorders such as multiple myeloma.

What is the role of light-chain staining in amyloidosis?

Light-chain immunostaining helps identify AL amyloidosis by demonstrating kappa or lambda light-chain restriction within amyloid deposits.

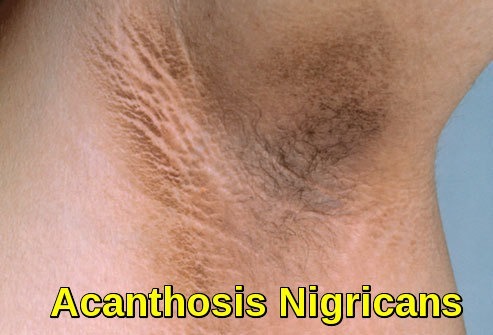

What are the skin manifestations of amyloidosis?

Cutaneous amyloidosis may present with hyperpigmented patches, papules, nodules, purpura, or waxy skin changes due to dermal amyloid deposition.

What is macroglossia and why does it occur in amyloidosis?

Macroglossia refers to tongue enlargement caused by amyloid deposition and is a characteristic feature of systemic AL amyloidosis.

Can amyloidosis cause nephrotic syndrome?

Yes, amyloidosis is a common cause of nephrotic syndrome due to heavy proteinuria from glomerular amyloid deposition.

How is amyloidosis definitively diagnosed?

Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy showing Congo red–positive amyloid deposits, followed by accurate amyloid typing.

Why is amyloid typing important?

Amyloid typing determines the specific amyloidosis subtype, which is essential for guiding treatment and predicting prognosis.

Is early diagnosis of amyloidosis important?

Early diagnosis is critical, as delayed recognition is common and is associated with advanced organ damage and poorer outcomes.

References:

Baker KR, Rice L. The amyloidoses: clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 2012;8(3):3–7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3487569/

Leung N, Nasr SH, Sethi S. How I diagnose amyloidosis. Blood. 2012;120(13):2451–2462.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/120/13/2451/30560/How-I-diagnose-amyloidosis

Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(6):583–596. doi:10.1056/NEJMra023144

Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and investigation of AL amyloidosis. British Journal of Haematology. 2015;168(2):207–218.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjh.13156

Mayo Clinic Staff. Amyloidosis – Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/amyloidosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353178

Kyle RA. Amyloidosis: a convoluted story. British Journal of Haematology. 2001;114(3):529–538.

Lachmann HJ, Booth DR, Booth SE, et al. Misdiagnosis of hereditary amyloidosis as AL (primary) amyloidosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(23):1786–1791. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013354

Comenzo RL. How I treat amyloidosis. Blood. 2009;114(15):3147–3157. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-209072

Falk RH, Comenzo RL, Skinner M. The systemic amyloidoses. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(13):898–909. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709253371306

Dubrey SW, Cha K, Andersen J, et al. Clinical features of immunoglobulin light-chain (AL) amyloidosis with heart involvement. QJM. 1998;91(2):141–157.

Stanford Health Care. Amyloidosis – Overview and treatment.

https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/blood-heart-circulation/amyloidosis.html

Shiel WC Jr. Amyloidosis. MedicineNet.

https://www.medicinenet.com/amyloidosis/article.htm

WebMD Editorial Team. Amyloidosis: Symptoms, causes, treatment, and prognosis.

https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/amyloidosis

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Diagnosis of amyloidosis.

https://www.cedars-sinai.org/programs/cancer/we-treat/multiple-myeloma-and-amyloidosis/conditions/diagnosis.html

UCSF Health. Treatment of amyloidosis.

https://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/amyloidosis/

Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Overview of amyloidosis.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/hematology-and-oncology/amyloidosis/overview-of-amyloidosis

StatPearls Publishing. Amyloidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482308/

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). Amyloidosis.

https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/amyloidosis/

Keywords:

amyloidosis, systemic amyloidosis, amyloidosis symptoms, amyloidosis causes, amyloidosis diagnosis, amyloidosis treatment, amyloidosis types, AL amyloidosis, AA amyloidosis, ATTR amyloidosis, hereditary amyloidosis, wild type ATTR amyloidosis, light chain amyloidosis, transthyretin amyloidosis, cardiac amyloidosis, renal amyloidosis, cutaneous amyloidosis, gastrointestinal amyloidosis, hepatic amyloidosis, amyloidosis heart, amyloidosis kidneys, amyloidosis nerves, amyloidosis skin, nephrotic syndrome amyloidosis, amyloidosis macroglossia, amyloidosis biopsy, Congo red staining amyloidosis, apple green birefringence amyloidosis, amyloid fibrils, amyloid protein deposition, amyloidosis echocardiography findings, cardiac amyloidosis MRI, late gadolinium enhancement amyloidosis, amyloidosis restrictive cardiomyopathy, amyloidosis heart failure, amyloidosis diagnosis criteria, amyloidosis diagnostic tests, amyloidosis prognosis, amyloidosis life expectancy, amyloidosis management, amyloidosis complications, amyloidosis early diagnosis, amyloidosis hematology overview, amyloidosis specialist, Ask Hematologist amyloidosis, Dr Moustafa Abdou hematology

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now