Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

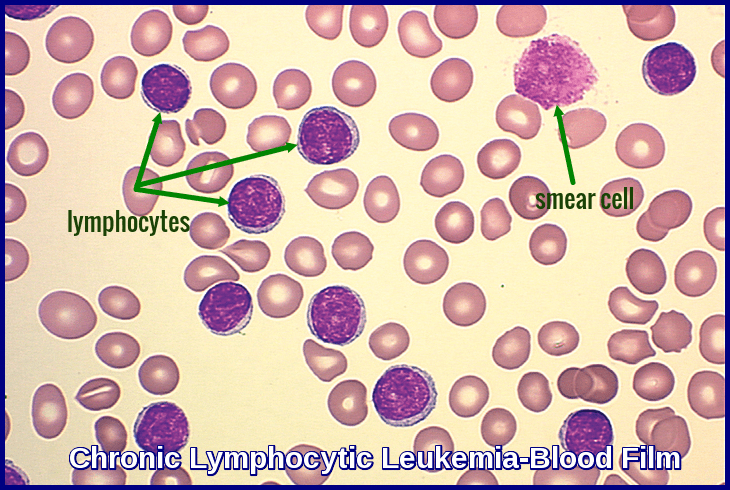

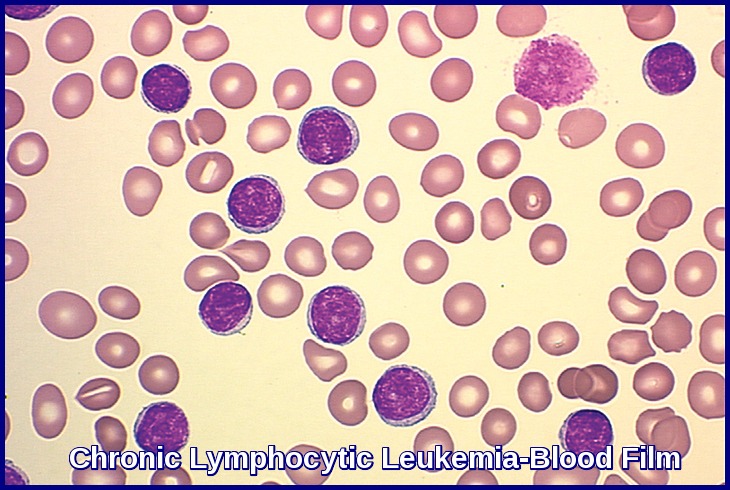

Peripheral blood smear demonstrating the typical features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including small mature lymphocytes and smudge cells.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is a low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative malignancy characterized by the accumulation of small, mature lymphocytes in the blood, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and spleen. It represents the most common form of leukemia in adults across the Western world and often presents with lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy, or incidental findings on routine blood tests. CLL is classified under ICD-10 code C91.1.

Clinical Features:

CLL occurs mainly in the elderly; 75% of cases are diagnosed in patients > 60 years. CLL is twice as common in men. Although the cause is unknown, some cases appear to have a hereditary component. The disease is rare in Japan and China.

There is usually gradual onset of fatigue, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Infections are not infrequent and bleeding problems occur in the last stages of the disease.

On examination, there is usually lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Hepatomegaly is usually a late feature.

CLL is confirmed by examining the peripheral smear and bone marrow; the hallmark is sustained, absolute peripheral lymphocytosis (> 5000/μL) and increased lymphocytes (> 30%) in the bone marrow.

Pathophysiology:

In about 98% of cases, CD5+ B cells undergo malignant transformation, with lymphocytes initially accumulating in the bone marrow and then spreading to lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues, eventually inducing splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.

As CLL progresses, abnormal hematopoiesis results in anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and decreased immunoglobulin production.

Many patients develop hypogammaglobulinemia and impaired antibody response, perhaps related to increased T-suppressor cell activity.

Patients have increased susceptibility to autoimmune disease characterized by immune hemolytic anemia (usually Coombs test–positive) or immune thrombocytopenia and a modest increase in the risk of developing other cancers.

In 2 to 3% of cases, the clonal expansion is T cell in type, and even this group has a subtype (eg, large granular lymphocytes with cytopenias).

In addition, other chronic leukemic patterns have been categorized under CLL:

- Prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL).

- Leukemic phase of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Sézary syndrome).

- Hairy cell leukemia.

- Lymphoma progressing to leukemia (ie, leukemic changes that occur in advanced stages of malignant lymphoma).

Differentiation of these subtypes from typical CLL is usually made by using light microscopy and phenotyping.

Investigations:

There is usually a mild normocytic anemia. This becomes more marked as the disease progresses or if there is associated autoimmune hemolytic anemia (5-10%).

The granulocyte count and platelet count only to fall late in the disease.

Most cases of CLL are B-cell neoplasms, however, rare cases of CLL are T-cell neoplasms.

In patients with CLL, the full blood count (FBC) with differential shows absolute lymphocytosis, with more than 5000 B-lymphocytes/µL. Lymphocytosis must persist for longer than 3 months. Clonality must be confirmed by flow cytometry. The presence of a cytopenia caused by clonal bone marrow involvement establishes the diagnosis of CLL regardless of the peripheral B-lymphocyte count.

Patients with fewer than 5000 B-lymphocytes/µL with lymphadenopathy and without cytopenias more likely have small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), although this diagnosis should be confirmed by lymph node biopsy.

Patients with a clonal B-cell population less than 5000/µL without lymphadenopathy or organomegaly, cytopenia, or other disease-related symptoms have monoclonal B-lymphocytosis (MBL). MBL will progress to CLL at a rate of 1-2% per year.

Microscopic examination of the peripheral blood smear is indicated to confirm lymphocytosis. It usually shows small lymphocytes predominating and the presence of smudge (smear) cells, which are artifacts from lymphocytes damaged during the slide preparation.

Large atypical cells, cleaved cells, and prolymphocytes are also often seen on the peripheral smear and may account for up to 55% of peripheral lymphocytes. If this percentage is exceeded, prolymphocytic leukemia (B-cell PLL) is a more likely diagnosis.

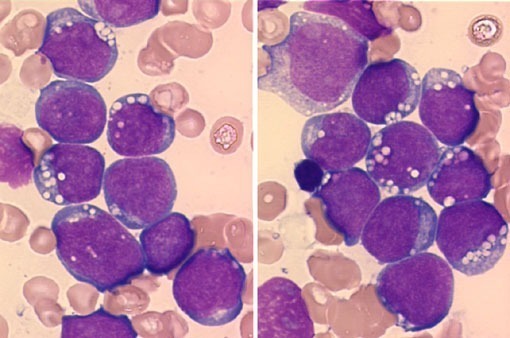

Peripheral blood smear demonstrating classic features of prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL), including large prolymphocytes with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli.

Peripheral blood flow cytometry is the most valuable test to confirm a diagnosis of CLL. It confirms the presence of circulating clonal B-lymphocytes expressing CD5 (normally expressed on T cells), CD19, CD20, CD23, and an absence of CD10 and FMC-7 staining. The cells express light-chain restricted monoclonal Ig, usually IgM ± IgD.

Flow cytometry scoring system used in the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), demonstrating the characteristic immunophenotype with weak sIg, positive CD5 and CD23, weak CD79b/CD22, and negative FMC7 expression.

Immunophenotyping is essential for the diagnosis of CLL. The scoring proposed in the modified Matutes score has been the basis of diagnosis for the past 15 years and is defined by strong expression of CD5 and CD23, low or absent expression of CD79b, sIgM, and FMC7.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy with flow cytometry are not required in all cases of CLL, but it may be necessary in selected cases to establish the diagnosis and to assess other complicating features such as anemia and thrombocytopenia. For example, bone marrow examination may be necessary to distinguish between thrombocytopenia of peripheral destruction (in the spleen) and that due to marrow infiltration.

Consider a lymph node biopsy if lymph nodes begin to enlarge rapidly in a patient with known CLL, to assess the possibility of transformation to a high-grade lymphoma. When such transformation is accompanied by fever, weight loss, and pain, it is termed Richter syndrome.

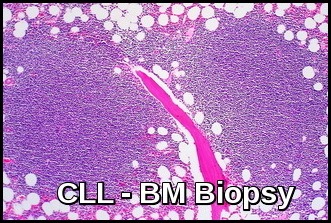

The bone marrow is infiltrated by small lymphocytes.

Bone marrow biopsy demonstrating diffuse lymphoid infiltration by small mature lymphocytes, a classic histopathologic feature of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

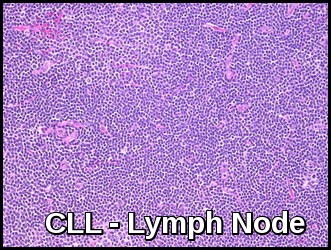

Biopsy of affected lymph nodes shows a diffuse infiltration with small lymphocytes.

Lymph node biopsy demonstrating diffuse architectural effacement and proliferation of small mature lymphocytes with pseudofollicles, consistent with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

hypogammaglobulinemia occurs in one-third; ‘M’ bands (usually IgM) are found in approximately 5%.

Consider obtaining serum quantitative immunoglobulin levels in patients developing repeated infections, because monthly intravenous immunoglobulin administration in patients with low levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (<0.5 gm) may be beneficial in reducing the frequency of infectious episodes.

A positive direct Coombs test (DCT) occurs in 25% of cases (usually without hemolysis) at some stage during the disease.

CLL Molecular Studies & Cytogenetics:

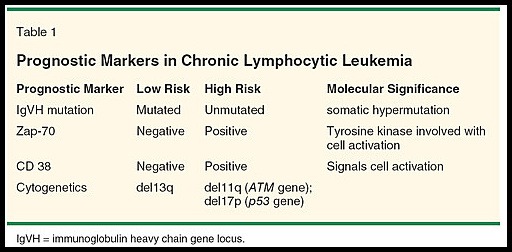

Summary of major prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), highlighting IgVH mutation status, ZAP-70 and CD38 expression, and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities including del11q and del17p.

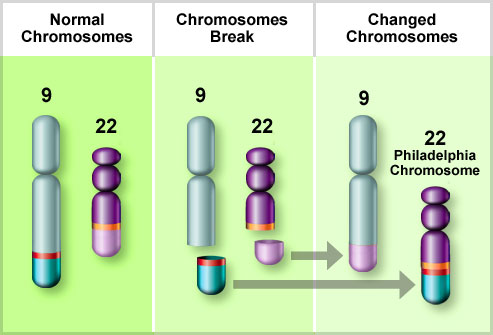

Genetic diagnostics of hematological malignancies has evolved dramatically over the years, from chromosomal banding analysis to next-generation sequencing (NGS), with a corresponding increased capacity to detect clinically relevant prognostic and predictive biomarkers. In diagnostics of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)-based analysis is used to detect recurrent chromosomal aberrations (del(11q), del(13q), del(17p) and trisomy 12) as well as targeted sequencing (IgVH and TP53 mutational status) for risk-stratifying purposes.

Chromosomal evaluation using FISH can identify certain chromosomal abnormalities of CLL with prognostic significance.

Patients with a deletion in the short arm of chromosome 17 [del(17p)/p53 gene] tend to have a worse prognosis, as well as resistance to therapy with alkylating agents and purine analogues.

Patients with deletions in the long arm of chromosome 11 [del(11q)/ATM gene] also have a worse prognosis and bulky lymphadenopathy at presentation.

The poor prognosis seen with del(17p) and del (11q) are independent of the patient’s stage at presentation. Patients with these abnormalities may benefit from treatment with the monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab.

IgVH status has shown potential as a prognostic marker for CLL as well. ZAP-70 and CD38 expression tend to correlate with unmutated IgVH and a poorer prognosis; however, these associations are not absolute.

These analyses are performed before start of any line of treatment and assist in clinical decision-making including selection of targeted therapy (BTK and BCL2 inhibitors).

None of the poor prognostic markers has been validated as an indication to initiate treatment in asymptomatic patients.

Practical Approach:

In most cases of CLL with sufficient disease burden in the blood, peripheral blood sampling is sufficient and preferable for molecular and cytogenetic analyses.

If peripheral disease is sparse, a bone marrow aspirate is a perfectly acceptable sample for:

- TP53 mutation analysis

- FISH studies

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels — if broader mutational profiling is required (e.g., NOTCH1, SF3B1, BIRC3) > blood or marrow aspirate can be used.

Trephine biopsy samples may be used for some analyses, but molecular sensitivity is lower due to fixation artefacts.

Staging:

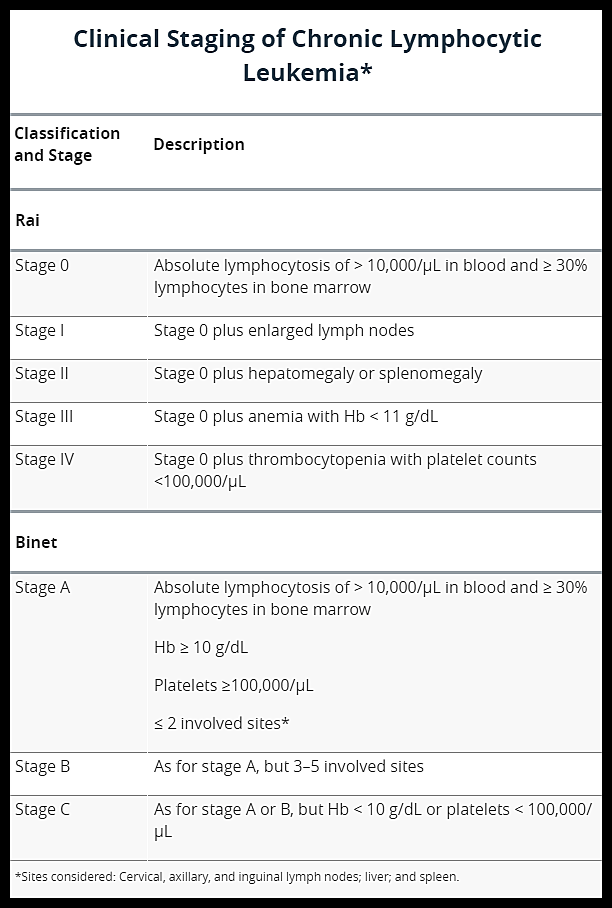

Two staging systems are in common use for CLL: the modified Rai staging in the United States and the Binet staging in Europe. Neither is completely satisfactory, and both have often been modified.

Clinical staging systems for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), showing the Rai (stages 0–IV) and Binet (stages A–C) classifications based on lymphocyte count, nodal involvement, organomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.

Differential Diagnosis:

The differential diagnosis of CLL includes several other entities, such as hairy cell leukemia, which is moderately positive for surface membrane immunoglobulins of multiple heavy-chain classes and is typically negative for CD5 and CD21.

Prolymphocytic leukemia has a typical phenotype that is positive for CD19, CD20, and surface membrane immunoglobulin; one-half will be negative for CD5.

Large granular lymphocytic leukemia has a natural killer (NK) cell phenotype (CD2, CD16, and CD56) or a T-cell immunophenotype (CD2, CD3, and CD8).

The pattern of positivity for CD19, CD20, and the T-cell antigen CD5 is shared only by mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); these cells generally do not express CD23.

Treatment:

- Symptom amelioration.

- Supportive care.

- Specific therapy.

Patients with CLL do not need to be treated with chemotherapy until they become symptomatic or display evidence of rapid progression of disease, as characterized by the following:

- Weight loss of more than 10% over 6 months.

- Extreme fatigue.

- Fever related to leukemia for longer than 2 weeks.

- Night sweats for longer than 1 month.

- Progressive marrow failure (anemia or thrombocytopenia).

- Autoimmune anemia or thrombocytopenia not responding to steroids.

- Progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly.

- Massive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy.

- Progressive lymphocytosis, as defined by an increase of > 50% in 2 months or a doubling time of less than 6 months.

Supportive care includes:

- Transfusion of packed RBCs or erythropoietin injections for anemia.

- Platelet transfusions for bleeding associated with thrombocytopenia.

- Antimicrobials for bacterial, fungal, or viral infections.

Because neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia limit bacterial killing, antibiotic therapy should be bactericidal. Therapeutic infusions of γ-globulin should be considered in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia and repeated or refractory infections or for prophylaxis when ≥ 2 severe infections occur within six months.

Specific therapy includes:

- Chemotherapy.

- Corticosteroids.

- Monoclonal antibody therapy.

- Radiation therapy.

These modalities may alleviate symptoms and prolong survival. Overtreatment is more dangerous than undertreatment.

Chemotherapy:

Alkylating drugs, especially chlorambucil, alone or with corticosteroids, have long been the usual therapy for B-cell CLL. However, fludarabine is more effective. Combination chemotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) more often induces complete remissions. It also lengthens remission duration and prolongs survival.

A phase III trial comparing bendamustine to chlorambucil in treatment-naive patients who were not deemed candidates for more aggressive regimens like FCR showed no improvement in overall survival but did show a complete response (21% vs 10%) and progression-free survival (21 months vs 9 months) favoring bendamustine without compromising the quality of life.

A bendamustine/rituximab combination has had some renewed interest. In a German phase II study of 72 pretreated patients, the overall response rate was 59%, and PFS was almost 15 months.

Patients with prolymphocytic leukemia and lymphoma leukemia usually require multidrug chemotherapy e.g. rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and often respond only partially.

Interferon alfa, deoxycoformycin, and 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine) are highly effective for hairy cell leukemia.

Corticosteroids:

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia are indications for corticosteroids.

Prednisone 1 mg/kg po once/day may occasionally result in striking, rapid improvement in patients with advanced CLL, although the response is often brief. The metabolic complications and increasing rate and severity of infections warrant caution in its prolonged use.

Prednisone used with fludarabine increases the risk of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and Listeria infections and requires PCP prophylaxis with oral septrin or pentamidine inhalation.

Monoclonal antibody therapy:

Rituximab is the first monoclonal antibody used in the successful treatment of lymphoid cancers. In previously untreated patients, the response rate is 75%, with 20% of patients achieving complete remission.

Alemtuzumab (MabCampath) has a 33% response rate in previously treated patients refractory to fludarabine and a 75 to 80% response rate in previously untreated patients. More problems with immunosuppression occur with alemtuzumab than with rituximab.

Rituximab has been combined with fludarabine and with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; these combinations have markedly improved the complete remission rate in both previously treated and untreated patients.

Alemtuzumab is now being combined with rituximab and with chemotherapy to treat minimal residual disease (MCR) and has effectively cleared bone marrow infiltration. Reactivation of cytomegalovirus and other opportunistic infections has occurred with alemtuzumab. Reactivation of hepatitis B infection may occur with rituximab.

Obinutuzumab (Gazyva) is a newer CD20-directed cytolytic monoclonal antibody that targets the same CLL cell surface protein as rituximab. The combination of obinutuzumab and chlorambucil was recently found to be superior to rituximab in prolonging progression-free survival and achieving a complete response to treatment. In combination with bendamustine, obinutuzumab can be used for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) who have had prior therapy with a rituximab-containing regimen.

Obinutuzumab (Gazyva) is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody used in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), often combined with targeted agents or chemotherapy.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors:

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that plays a central role in the signal transduction of the B-cell antigen receptor and other cell surface receptors, both in normal and malignant B lymphocytes. B-cell antigen receptor signaling is activated in secondary lymphatic organs and drives the proliferation of malignant B-cells, including CLL cells. During the last 10 years, BTK inhibitors (BTKi) are increasingly replacing chemotherapy-based regimens, especially in patients with CLL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). BTKi are particularly active in patients with CLL and MCL, but also received approval for Waldenström macroglobulinemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Current clinical practice is continuous long-term administration of BTKi, which can be complicated by adverse effects or the development of drug resistance. Alternatives to long-term use of BTKi are being developed, such as combination therapies, permitting limited duration therapy. Second-generation BTKi are under development, which differ from ibrutinib, the first-in-class BTKi, in their specificity for BTK, and therefore may differentiate themselves from ibrutinib in terms of adverse effects or efficacy.

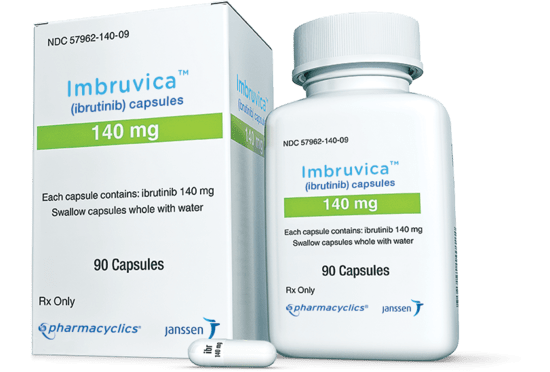

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) is a novel, oral inhibitor of BTK. Ibrutinib appears to be highly active in CLL, particularly in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutations, and has induced durable remissions in some patients with relapsed or refractory CLL. Its role as a single agent or as part of combination chemotherapy is evolving. Ibrutinib is also active in relapsed or refractory MCL and Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Ibrutinib monotherapy and idelalisib in combination with rituximab induce responses in the majority of patients in whom chemoimmunotherapy has failed, and these patients have improved outcomes.

Imbruvica (ibrutinib) 140 mg capsules, an oral BTK inhibitor widely used in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma, and other B-cell disorders.

Ibrutinib is indicated for CLL/SLL as a monotherapy or in combination with rituximab or obinutuzumab, or with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) combination at a dose of 420 mg PO daily until unacceptable toxicity or disease progression. Ibrutinib is also indicated in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least 1 previous therapy at a dose of 560 mg PO daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Acalabrutinib (Calquence) is a novel second-generation BTK inhibitor and has shown promising safety and efficacy profiles in patients with relapsed CLL and pretreated MCL. Recently, acalabrutinib was approved by the FDA for the treatment of adult patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who received at least one prior therapy. However, clinical trials on a direct comparison between ibrutinib and acalabrutinib and on combination treatment options with other agents such as CD20 antibodies are warranted.

Calquence (acalabrutinib) 100 mg capsules, a highly selective second-generation BTK inhibitor approved for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other B-cell malignancies.

The way that both acalabrutinib and ibrutinib work is by irreversibly binding to and destroying the cancerous B lymphocytes. Acalabrutinib’s increased selectivity means that the risk of off-target cells, or noncancerous cells, is much lower than in ibrutinib, which thus results in a lower risk of adverse effects. Acalabrutinib is indicated for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) at a dose of 100 mg PO q12hr until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Zanubrutinib (BRUKINSA), a next-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, is approved in the UK for selected patients with treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). According to NICE, zanubrutinib is recommended as a first-line option only for adults with untreated CLL who have a 17p deletion or TP53 mutation, or for those without these abnormalities but who are unsuitable for FCR or bendamustine-rituximab chemo-immunotherapy. This positions zanubrutinib as an important targeted therapy for high-risk or chemo-ineligible patients.

Brukinsa (zanubrutinib) 80 mg capsules, a selective BTK inhibitor approved for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including first-line use in patients with 17p deletion, TP53 mutation, or those unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Idelalisib (Zydelig 150mg tablets) is indicated in combination with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab or ofatumumab) for the treatment of adult patients with CLL who have received at least one prior therapy, or as first-line treatment in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in patients who are not eligible for any other therapies.

BCL-2 inhibitors:

In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted breakthrough therapy designation to venetoclax (Venclexta) for subjects with CLL who have relapsed or have been refractory to previous treatment and have the 17p deletion genetic mutation. Venetoclax is a highly selective inhibitor of BCL2, which was shown to have substantial anti-tumor activity in patients with relapsed CLL, including those with poor prognostic features. Responses appeared to be more durable among those who had a complete response than among those with a partial response. Gradual dose escalation appeared to minimize the risk of tumor lysis syndrome, the major toxicity associated with venetoclax. Targeted treatment with venetoclax–obinutuzumab has been shown to be effective in previously untreated patients with CLL and coexisting conditions and resulted in a significantly higher percentage of patients with PFS than standard treatment with chlorambucil–obinutuzumab.

In Ireland, since December 2018, venetoclax has been reimbursed for the treatment of CLL in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in adult patients who are unsuitable for or have failed a B-cell receptor pathway inhibitor; and in the absence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in adult patients who have failed both chemoimmunotherapy and a B-cell receptor pathway inhibitor. Since 2020 it has been reimbursed in combination with rituximab for the treatment of adult patients with CLL who have received at least one prior therapy; and, as of March 2022, in combination with obinutuzumab for the treatment of adult patients with previously untreated CLL.

The combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia as compared with chemoimmunotherapy. Measurable residual disease (MRD) directed ibrutinib–venetoclax improved progression-free survival compared with fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab (FCR), and results for overall survival also favored ibrutinib–venetoclax.

Monoclonal antibodies are generally well tolerated, although they may cause allergic reactions and significant immunosuppression. This favorable toxicity profile allows these agents to be combined with conventional chemotherapy, often with excellent clinical efficacy.

Radiation therapy:

Local irradiation for palliation may be given to areas of lymphadenopathy or for liver and spleen involvement that does not respond to chemotherapy. Total body irradiation in small doses is occasionally successful in temporarily ameliorating symptoms.

CAR T-cell therapy:

In chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a patient’s own genetically modified T-cells are engineered to express receptors that latch on to a specific cell surface protein, connecting them to cancer cells to be destroyed.

CAR T-cell therapy has already achieved remarkable remissions in some difficult-to-treat patients with B-cell malignancies. Although the clinical experience in CLL patients is limited, the proportion of remissions reached in this disease is clearly the lowest in the spectrum of B-cell tumors.

Currently, CAR T-cell therapy is US FDA approved as the standard of care for:

- Some forms of aggressive, relapsed, or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, transformed follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma.

- Relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma.

- Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.

- Relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

There are also many clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapy for other types of blood cancer and solid tumors.

CAR-T therapy is available in more than 15 EU countries, has been publicly available in England through the NHS since 2018, and has very recently made its way to Ireland.

In the United States the increasing number of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, innovative, and potentially effective commercial cancer therapies pose a significant financial burden on public and private payers. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells are prototypical of this challenge. In 2017 and 2018, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, Novartis) and axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta, Kite) were approved by the FDA for use after showing groundbreaking results in relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies. In 2020 and 2021, four further submissions to the FDA are expected for CAR T-cell therapies for indolent and aggressive B-cell malignancies and plasma cell myeloma. Yet, with marketed prices of over $350,000 per infusion for the two FDA-approved therapies and similar price tags expected for the coming products, serious concerns are raised over value and affordability.

Prognosis:

The median survival of patients with B-cell CLL or its complications is about 7 to 10 yr. Patients in Rai stage 0 to II at diagnosis may survive for 5 to 20 yr without treatment. Patients in Rai stage III or IV are more likely to die within 3 to 4 yr of diagnosis. Progression to bone marrow failure is usually associated with short survival. Patients with CLL are more likely to develop secondary cancer, especially skin cancer.

Questions and Answers:

What is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)?

CLL is a slow-growing B-cell lymphoproliferative malignancy characterized by the accumulation of small mature lymphocytes in the blood, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues. It is the most common leukemia in adults in Western countries.

What are the early symptoms of CLL?

Many patients have no symptoms at diagnosis. When symptoms occur, they may include fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, recurrent infections, lymphadenopathy, or abdominal fullness due to splenomegaly.

How is CLL diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on persistent lymphocytosis (≥5 × 10⁹/L clonal B-lymphocytes for ≥3 months), classic flow cytometry immunophenotype (CD5+, CD23+, weak sIg), blood film findings such as smudge cells, and prognostic testing (FISH for del17p, del11q, trisomy 12; TP53 mutation; IGHV status).

What are the stages of CLL?

CLL is staged using the Rai (0–IV) or Binet (A–C) systems, based on lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Staging helps estimate prognosis and guide follow-up intensity.

What are the current treatment options for CLL?

First-line therapy increasingly relies on targeted agents such as BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib for eligible patients) and venetoclax-based combinations. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., obinutuzumab) may be used alone or in combination, while chemo-immunotherapy remains suitable only for selected patients.

Can CLL be cured?

Currently, CLL is considered incurable with conventional therapy, but many patients live normal or near-normal lifespans. Curative potential exists only with allogeneic stem cell transplantation, reserved for select high-risk cases.

References:

Mir, M.A. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Medscape. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/199313

Badoux, X.C., Keating, M.J., Wang, X., et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemo-immunotherapy is highly effective in relapsed CLL. Blood. 2011.

Hallek, M., Cheson, B.D., Catovsky, D., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: iwCLL update of the NCI-WG 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446-5456.

Abbott, B.L. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Oncologist. 2006;11(1):21-30.

Zwiebel, J.A., Cheson, B.D. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: staging and prognostic factors. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(1):42-59.

Hillmen, P., Skotnicki, A.B., Robak, T., et al. Alemtuzumab vs chlorambucil as first-line therapy for CLL. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5616-5623.

Fischer, K., Cramer, P., Busch, R., et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab for relapsed/refractory CLL: a GCLLSG phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3559-3566.

Furman, R.R., Sharman, J.P., et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed CLL. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:997-1007.

Fiorenza, S., Ritchie, D.S., Ramsey, S.D., et al. Value and affordability of CAR-T cell therapy in the U.S. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:1706-1715.

Kriegsmann, K., Kriegsmann, M., Witzens-Harig, M. Acalabrutinib: A second-generation BTK inhibitor. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018;212:285-294.

Mollstedt, J., Mansouri, L., Rosenquist, R. Precision diagnostics in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: past, present and future. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1146486.

Munir, T., Cairns, D.A., Bloor, A., Allsup, D., et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy guided by measurable residual disease. N Engl J Med. 2024.

NICE. Zanubrutinib for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Technology Appraisal TA931. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2023.

International Workshop on CLL (iwCLL) 2018 – Updated diagnostic and treatment criteria for CLL. Blood. (High-authority modern guideline).

Obinutuzumab (Gazyva). Chemotherapy Drug Information. Chemocare. Available at: http://chemocare.com/chemotherapy/drug-info/obinutuzumab.aspx

Keywords:

chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia symptoms, chronic lymphocytic leukemia diagnosis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia tests, chronic lymphocytic leukemia blood film, CLL smudge cells, CLL lymph node biopsy, CLL bone marrow biopsy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia flow cytometry, CLL immunophenotyping, CLL staging, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stages, Rai staging CLL, Binet staging CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 0, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 0 life expectancy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 1, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 2, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 3, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 4, chronic lymphocytic leukemia stage 4 life expectancy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia prognosis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia survival rate, chronic lymphocytic leukemia life expectancy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment, chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment options, CLL targeted therapy, CLL BTK inhibitors, ibrutinib for CLL, acalabrutinib for CLL, zanubrutinib for CLL, CLL obinutuzumab, CLL bendamustine rituximab, CLL chemoimmunotherapy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia new treatments, chronic lymphocytic leukemia novel agents, CLL PI3K inhibitors, CLL CAR T-cell therapy, CLL measurable residual disease, MRD-guided therapy CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia cytogenetics, CLL 17p deletion, CLL TP53 mutation, CLL del13q, CLL high-risk disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia ICD-10, CLL ICD 10 code C91.1, chronic lymphocytic leukemia small lymphocytic lymphoma, CLL SLL, CLL complications, CLL infection risk, CLL immunodeficiency, Ask Hematologist, Dr Moustafa Abdou, Dr Abdou Ask Hematologist, AskHematologist.com CLL

Request Online Consultation With Dr M Abdou

Fee: US$100

Secure payment via PayPal (credit and debit cards accepted)

Pay Now