Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia

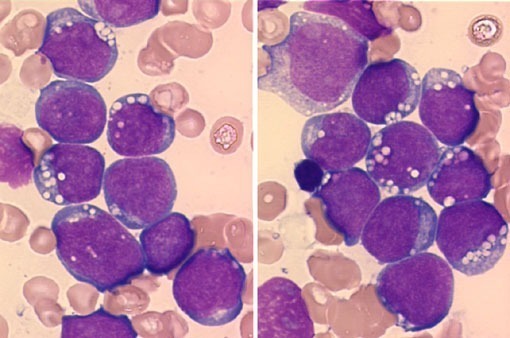

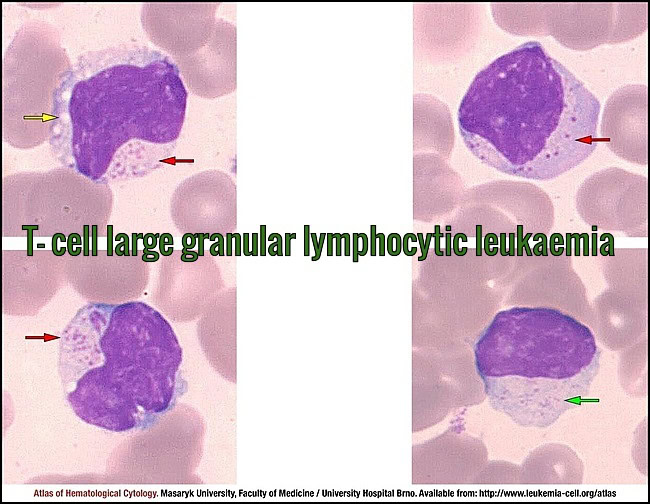

Large granular lymphocytic leukemia blood smear demonstrating a large granular lymphocyte with azurophilic granules.

Large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia is a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by a persistent (>6 months) increase in circulating large granular lymphocytes, typically associated with cytopenias, autoimmune features, and clonal T-cell or NK-cell proliferation.

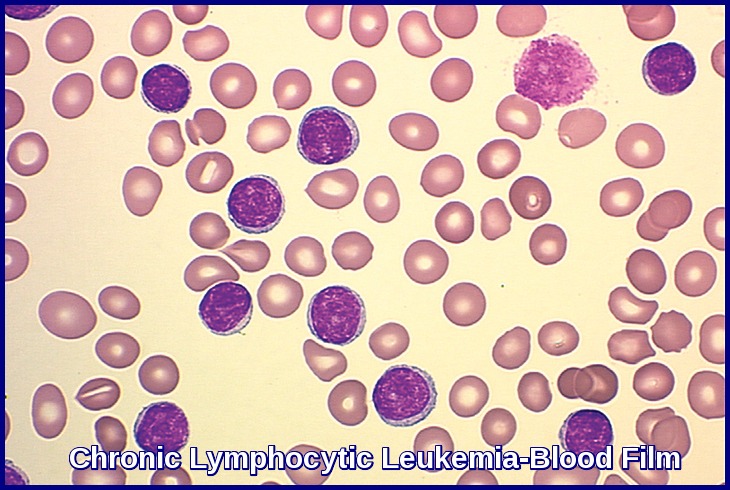

Large granular lymphocytic leukemia is an uncommon condition also described as CD8 lymphocytosis with neutropenia or T-lymphoproliferative disease. Peripheral blood lymphocytosis comprises cells with round or oval nuclei with moderately condensed chromatin and rare nucleoli, eccentrically placed in the abundant pale blue cytoplasm with azurophilic granules. The ICD-10 code for T-LGL is C91.50.

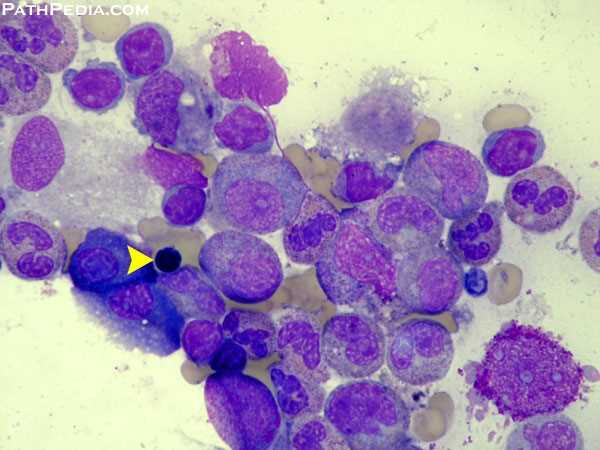

Peripheral blood smear (MGG, 1000×) showing large granular lymphocytes with oval to irregular nuclei, abundant slightly basophilic cytoplasm, and prominent azurophilic granules (red arrows). Coarse granulation is typical, while very fine microgranular variants may occur (green arrow). Occasional cytoplasmic vacuolisation is present (yellow arrow), consistent with T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Courtesy of the Atlas of Haematological Cytology, Masaryk University (leukemia-cell.org).

Large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia has been recognized by the World Health Organization classifications amongst mature T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms. There are 3 categories: chronic T-cell leukemia and NK-cell lymphocytosis, which are similarly indolent diseases characterized by cytopenias and autoimmune conditions as opposed to aggressive NK-cell LGL leukemia.

LGLs comprise 10 to 15 percent of normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. The absolute number of LGLs in the peripheral blood of normal subjects is 0.2-0.4×109/L.

LGLs arise from two major lineages. About 85 percent of normal LGLs have an NK cell phenotype, and only 15 percent are derived from T cells. The phenotypes of LGLs in LGL leukemia, however, are just the opposite:

CD3 positive T cell lineage.

CD3 negative NK cell lineage.

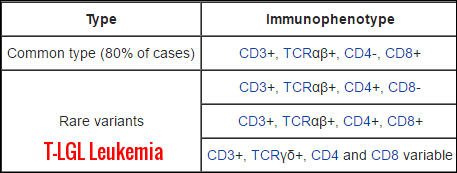

The postulated cells of origin of T-LGL leukemia are transformed CD8+ T-cell with clonal rearrangements of β chain T-cell receptor genes for the majority of cases and a CD8- T-cell with clonal rearrangements of γ chain T-cell receptor genes for a minority of cases.

While the exact cause of LGL leukemia is unknown, autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are diagnosed before the onset of LGL leukemia in about 20 percent of cases.

Chronic antigenic stimulation with exogenous antigens such as human T-cell lymphotrophic virus (HTLV) may be also responsible for inducing the activation and clonal expansion of effector CD8+ LGLs.

The median age at diagnosis is 60 years without gender predilection.

There are two major lineages, one being T-cell (indolent) and the other having a natural killer (NK) cell phenotype (more aggressive).

The disease was first described in 1985 as a clonal disorder involving tissue invasion of marrow, spleen, and liver.

Clinical presentation is dominated by recurrent infections associated with neutropenia, anemia, splenomegaly, and autoimmune diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

In 1989, the French-American-British classification identified LGL leukemia as a distinct entity among chronic T-lymphoid leukemias.

In 1993, the distinction was made between CD3+ T-cell and CD3− NK-cell lineage subtypes of LGL leukemia.

Furthermore, in 2008, a new provisional entity of chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells (also known as chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis) was created by World Health Organization to distinguish it from the much more aggressive form of NK-cell leukemia.

The frequency of T and NK LGL leukemia is not accurately determined and ranges from 2% to 5% of the chronic lymphoproliferative diseases in North America and up to 5% to 6% in Asia.

Clinical features:

This disease is known for an indolent clinical course and incidental discovery. The most common physical finding is moderate splenomegaly. B symptoms are seen in a third of cases, and recurrent infections due to the associated neutropenia are seen in almost half of cases.

Rheumatoid arthritis is commonly observed in patients with T-LGL, leading to a clinical presentation similar to Felty’s syndrome. Signs and symptoms of anemia are commonly found, due to the association between T-LGL and erythroid hypoplasia.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of T-cell LGL leukemia is based on the presence of an LGL lymphocytosis (typically 2-20×109/L), characteristic immunophenotype, and confirmation of clonality using T-cell receptor gene rearrangement (TCR-GR) studies. The gene for the β chain of the TCR is found to be rearranged more often than the γ chain of the TCR.

Reactive LGL lymphocytosis and persistent poly-clonal LGL lymphocytosis,due to viral infections,aging, and hematopoietic cell transplantation, should be considered prior to establishing a diagnosis of T-cell LGL leukemia.

Morphologically, LGLs are medium to large cells containing abundant cytoplasm, coarse azurophilic granules, and eccentric nuclei.

T-cell LGL leukemic cells typically coexpress CD3+CD8+CD57+ markers.

Aberrantly weaker expression of pan-T-cell markers such as CD5 and CD7 can also be helpful in differentiating malignant T-cell LGL populations from reactive expansions of LGLs.

Immunophenotype patterns of T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia, highlighting the common CD3+ TCRαβ+ CD8+ subtype and the rarer TCRγδ+ variants with variable CD4/CD8 expression.

A bone marrow biopsy/aspirate is not required for diagnosing the majority of T-cell LGL cases. However, in asymptomatic patients with absolute LGL counts that are <0.5 × 109/L, an evaluation of the marrow is essential.

Examination of the marrow will demonstrate clonal populations of LGLs in an interstitial pattern. Immunohistochemistry using anti-CD3 antibodies can be helpful in visualization and enumeration of the malignant T-cell population. The extent of marrow involvement is highly variable and does not correlate with the severity of symptoms or the degree of cytopenias.

The majority of T-cell LGL cases will manifest a normal karyotype. Fewer than 10% of cases will exhibit karyotypic abnormalities, which include trisomies of chromosomes 3, 8, and 14, deletions of chromosomes 6 and 5q, and inversions of 12p and 14q.

Treatment:

The management of asymptomatic patients with this disorder is careful observation.

The indications for treating patients with T-cell LGL leukemia are the development of recurrent infections, severe neutropenia, symptomatic anemia or thrombocytopenia, symptomatic splenomegaly, and the presence of B-symptoms.

The improvement of symptoms secondary to therapy may occur despite the failure to normalize neutrophil counts. Similarly, the failure to eradicate the malignant leukemic clone with therapy does not prevent improvements in underlying cytopenias.

Low-dose methotrexate at 10 mg/m2 per week has been effective in inducing responses. Approximately 50% of patients with T-cell LGL leukemia who are treated with single-agent methotrexate develop a complete response; however, patients may require indefinite treatment to maintain sustained responses.

Cyclophosphamide at 50 to 100 mg daily or cyclosporine A at 5 to 10 mg/kg daily are also effective therapeutic alternatives to methotrexate. Treatment should be continued for at least 4 months prior to altering the therapeutic regimen for lack of response.

Monotherapy with corticosteroids has activity in treating this disorder, but response duration seems to be less than with methotrexate, cyclosporine A, or cyclophosphamide alone. However, resolution of B symptoms and hematologic improvements may be more rapid if corticosteroids are used in combination with methotrexate or cyclophosphamide during the first month of therapy. Due to adverse side effects, prolonged administration (>1 month) of high-dose corticosteroids is not usually recommended. Prophylactic use of antibiotics can be beneficial, especially in patients with severe neutropenia, with concurrent corticosteroid treatment.

Osuji et al reported the expression of CD52 on all abnormal cells in patients with T-cell LGL leukemia and NK-cell leukemia using flow cytometry. Anecdotal reports describe the successful use of alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 humanized monoclonal antibody (Campath®), in the therapy of refractory T-cell LGL leukemia. Currently, a single phase II study sponsored by the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute is evaluating the efficacy and safety of alemtuzumab for the first-line treatment of T-cell LGL leukemia. Alemtuzumab at 10 mg per day is administered intravenously for 10 days. Response rates will be assessed at 3 months.

Durable responses have been anecdotally reported with the use of second-line therapies such as fludarabine, chlorodeoxyadenosine, and deoxycoformycin.

Prognosis:

The 5-year survival has been noted as 89% in at least one study from France of 201 patients with T-LGL leukemia.

Summary:

Large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia is a chronic clonal disorder of cytotoxic T cells or NK cells characterized by persistent lymphocytosis, cytopenias—especially neutropenia—autoimmune manifestations, and distinctive morphologic and immunophenotypic features. Diagnosis integrates clinical presentation, peripheral smear morphology showing large granular lymphocytes with azurophilic granules, flow cytometry confirming CD3+, TCRαβ+, CD8+ (or TCRγδ+ in rare variants), and molecular testing for STAT3 or STAT5b mutations. Management focuses on treating symptomatic cytopenias or autoimmune disease using low-dose immunosuppression such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or cyclosporine. Prognosis is generally indolent, with long-term disease control achievable in most patients.

Questions and Answers:

What is large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia?

LGL leukemia is a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder caused by clonal expansion of cytotoxic T cells or NK cells, presenting with persistent lymphocytosis, cytopenias, and autoimmune features.

What are the typical symptoms of LGL leukemia?

Patients often experience fatigue, recurrent infections from neutropenia, anemia-related symptoms, splenomegaly, and autoimmune manifestations such as rheumatoid arthritis.

How is LGL leukemia diagnosed?

Diagnosis relies on persistent LGL expansion for >6 months, blood smear morphology, flow cytometry immunophenotyping, T-cell clonality testing, and detection of STAT3 or STAT5b mutations.

What immunophenotype is seen in T-cell LGL leukemia?

The common subtype is CD3+, TCRαβ+, CD8+, while rare variants show TCRγδ+ expression with variable CD4/CD8 levels.

What is the difference between T-LGL leukemia and NK-LGL leukemia?

T-LGL leukemia is CD3+ and clonal, whereas NK-LGL leukemia is CD3− and typically diagnosed through NK-cell markers such as CD16 and CD56, with different mutation profiles and clinical behavior.

Is STAT3 mutation important in LGL leukemia?

Yes. STAT3 mutations occur in nearly half of T-LGL leukemia cases and support diagnosis while correlating with neutropenia and other immune-mediated features.

How is LGL leukemia treated?

Treatment is indicated for symptomatic cytopenias or autoimmune disease and typically includes low-dose methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, or corticosteroids.

Can LGL leukemia be cured?

There is no definitive cure, but most patients achieve durable disease control with immunosuppressive therapy and have a favorable long-term prognosis.

Is LGL leukemia associated with autoimmune diseases?

Yes. About one-third of patients have autoimmune disorders, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis linked to chronic immune activation and clonal T-cell proliferation.

When should treatment be started for LGL leukemia?

Therapy is initiated for severe neutropenia, recurrent infections, symptomatic anemia, transfusion dependence, or active autoimmune disease requiring control.

References: