Iron Deficiency Anemia

Fatigue and headaches are common symptoms of iron deficiency anemia, often caused by reduced oxygen delivery to tissues.

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common type of anemia, and it occurs when your body doesn’t have enough iron. Your body needs iron to make hemoglobin. When there isn’t enough iron in your bloodstream, the rest of your body can’t get the amount of oxygen it needs.

Iron is a mineral. Most of the iron in the body is found in the hemoglobin of red blood cells and in the myoglobin of muscle cells. Iron is needed for transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide. It also has other important roles in the body. In people with iron deficiency anemia, the red blood cells can’t carry enough oxygen to the body because they don’t have enough iron. People with this condition often feel very tired.

Iron helps red blood cells deliver oxygen from the lungs to cells all over the body. Once the oxygen is delivered, iron then helps red blood cells carry carbon dioxide waste back to the lungs to be exhaled. Iron also plays a role in many important chemical reactions in the body.

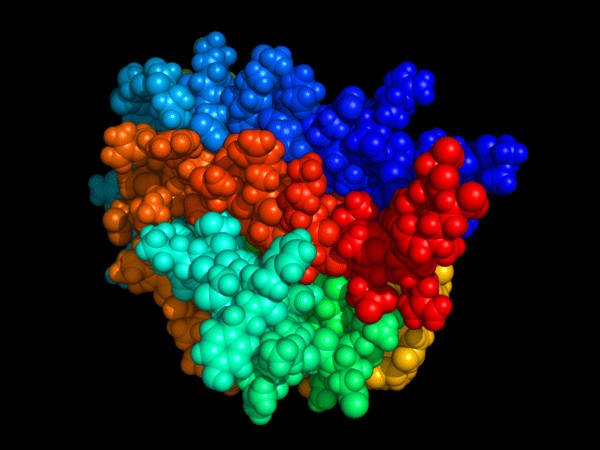

Ferritin:

What is the difference between ferritin and iron?

Ferritin is a good indicator of how much iron is stored within our body. For example, if a blood test reveals ferritin levels are low, this could be a sign of IDA. Approximately one-quarter of the total iron in the body is stored as ferritin. Ferritin has a vital function in the absorption, storage, and release of iron. It has a large iron core which can store up to 4000 iron atoms. These atoms are protected by the protein coat of the ferritin protein, called apoferritin. Most ferritin is found in the liver but it can also be present in the spleen, bone marrow, and the muscles.

Normal ferritin levels are between 13 and 150 µg/L, although this can change depending on the laboratory testing the sample.

It is important to note that ferritin levels can be raised in certain conditions, including:

- Inflammation

- Liver disease

- Malignancy

- Iron supplement therapy

- Significant tissue destruction

In these instances, the increased ferritin levels are not a reflection of the body’s iron stores.

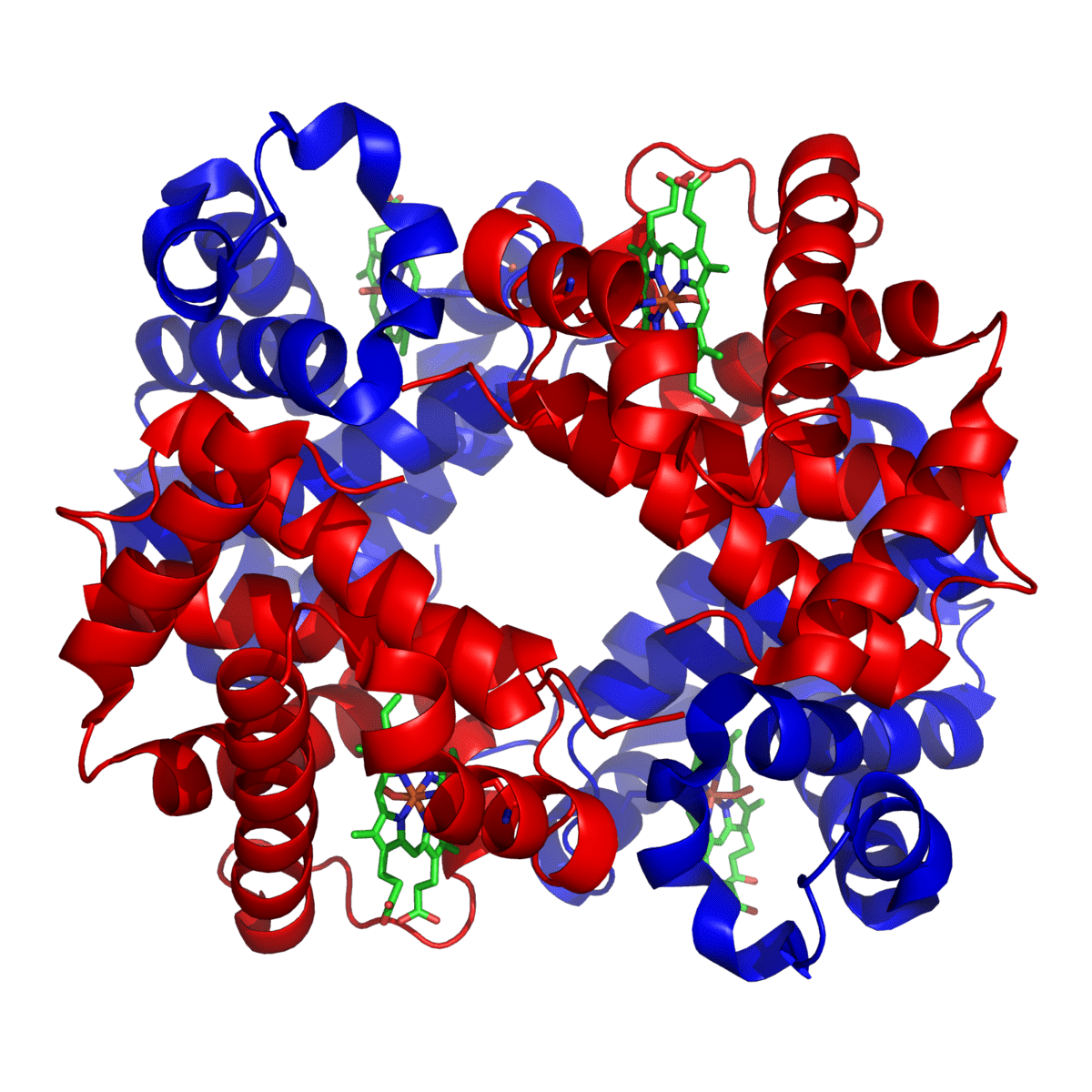

Transferrin and Iron-binding Capacity:

Transferrin is the main protein in the blood that binds to iron and transports it throughout the body. A transferrin test directly measures the level in the blood. Alternatively, transferrin may be measured indirectly (or converted by calculation) so that its level is expressed as the amount of iron it is capable of binding. This is called the total iron-binding capacity (TIBC).

Incidence of iron deficiency anemia:

Over 10% of Western urban populations are iron deficient though not all are anemic. In many other parts of the world, the incidence is still higher. Iron deficiency anemia is particularly common in women of childbearing age.

Causes:

1- Poor diet:

Foods rich in iron include:

- Red meat.

- Beef liver.

- Poultry.

- Seafood.

- Beans.

- Dark green leafy vegetables, such as spinach.

- Dried fruit, such as raisins and apricots.

- Iron-fortified cereals, bread, and pasta.

2- Malabsorption of iron:

- Following stomach surgery (rapid transit).

- Lack of stomach HCL acid (achlorhydria): stomach acidity is required for the absorption of iron.

- Coeliac disease.

3- Blood loss:

This may be due to heavy periods or bleeding from the bowel or urinary system.

Clinical Features:

- General features of anemia: tiredness, shortness of breath on effort, dizziness, and headaches.

- Angular stomatitis and atrophic glossitis.

- Brittle spoon-shaped nails (koilonychia).

- Brittle sparse hair.

- Pruritis vulvae (itching around female private parts).

- Rarely a posterior cricoid web may develop (Plummer-Vinson syndrome).

Angular stomatitis and glossitis are classic mucocutaneous signs of iron deficiency anemia, reflecting impaired epithelial repair and reduced iron stores.

Atrophic glossitis with a smooth, inflamed tongue is a characteristic mucosal manifestation of iron deficiency anemia due to impaired epithelial regeneration.

Koilonychia, or spoon-shaped nails, is a classic clinical sign associated with chronic iron deficiency anemia and impaired keratin synthesis.

Advanced spooning and thinning of the nail plate, characteristic of koilonychia seen in chronic iron deficiency anemia.

Investigations:

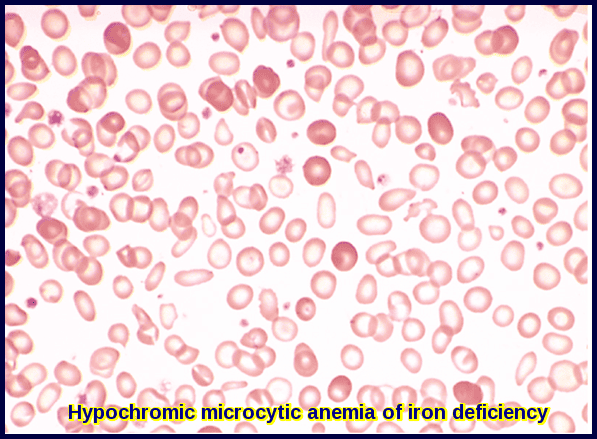

FBC (Full Blood Count) and Blood Film:

- Microcytosis (small red cells – MCV <78fl) appears first and progresses as anemia develops.

- Hypochromia (red cells contain less hemoglobin).

- Anisocytosis (variation in red cell size).

- Poikilocytosis (variation in red cell shape).

- Pencil cells are characteristic.

- White cell count and platelet count are usually normal, however, platelet count may rise if the cause of the iron deficiency is blood loss.

Peripheral blood film showing hypochromic microcytic red cells with marked anisopoikilocytosis, a classic morphological pattern of iron deficiency anemia.

Blood smear demonstrating hypochromic microcytic red cells with characteristic pencil cells, a hallmark morphological feature in iron deficiency anemia.

Biochemistry:

- Serum iron is low (normal range: 10-30 umol/L).

- Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) is high normal or raised (normal range: 40-70 umol/L).

- The % Iron Saturation (Transferrin Saturation) is usually <10% (serum iron/TIBC).

- Serum Ferritin is reduced (usually < 10 ug/dL), although it may be misleadingly higher if there is a coexistent inflammation, infection or malignancy.

Treatment:

Once iron deficiency is confirmed, it is essential to determine the underlying cause through detailed history-taking, targeted physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic investigations. Evaluation may include upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (OGD and colonoscopy) to identify occult GI blood loss, peptic disease, or coeliac disease, as well as pelvic ultrasound in women with menorrhagia to assess for uterine fibroids or other gynecological sources of bleeding.

Simply replacing iron is never sufficient; establishing the cause of iron deficiency is critical to prevent recurrence and detect potentially serious pathology. In older adults, iron deficiency anemia can be an early warning sign of colorectal cancer, and prompt gastrointestinal evaluation is vital to avoid delays in diagnosis.

Oral iron:

Oral iron is given to correct the anemia and then replete the body stores (3-6 months).

Iron is best absorbed on an empty stomach (usually if taken 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals). If stomach upset occurs, you may take it with food.

Ferrous sulfate 200mg three times daily is cheap and effective though the dose must be reduced in patients who experience side-effects!

Ferrous fumarate capsules (Galfer) 210 mg once or twice daily is also effective.

Oral iron may cause Gastrointestinal disturbances e.g. constipation, diarrhea, stomach discomfort, and feeling sick. Some patients are intolerant of oral iron and parenteral iron may be considered if the anemia is severe.

For patients who have difficulty tolerating oral iron supplements, administer smaller, more frequent doses; start with a lower dose and increase slowly to the target dose; try a different form or preparation, or take with or after meals or at bedtime.

Iron-drug interactions of clinical significance may occur in many patients and involve a large number of therapies. Concurrent ingestion of iron causes marked decreases in the bioavailability of a number of drugs e.g. tetracycline, tetracycline derivatives (doxycycline, methacycline, and oxytetracycline), penicillamine, methyldopa, levodopa, carbidopa, and ciprofloxacin. The major mechanism of these drug interactions is the formation of iron-drug complexes (chelation or binding of iron by the involved drug). A large number of other important and commonly used drugs such as thyroxine, captopril, and folic acid have been demonstrated to form stable complexes with iron.

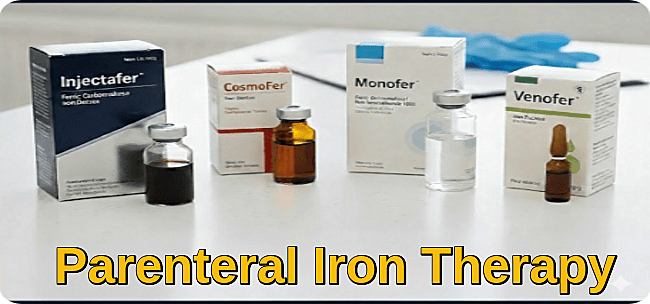

Parenteral iron:

This should only be used if oral iron cannot be tolerated or if negative iron balance persists.

There are many available preparations that can be given as an intravenous iron infusion in the hospital like Injectafer, CosmoFer, Monofer, and Venofer. Parenteral iron should only be administered under strict medical supervision.

Summary:

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common form of anemia worldwide and results from insufficient iron to support effective hemoglobin synthesis. It typically presents with fatigue, dizziness, headaches, exertional dyspnea, brittle hair, atrophic glossitis, angular stomatitis, and nail changes such as koilonychia. The condition arises from chronic blood loss, poor dietary intake, increased physiological demand, or malabsorption disorders including coeliac disease and post-gastrectomy states. Diagnosis is confirmed through microcytic hypochromic red cell indices, characteristic blood film features such as pencil cells and marked anisopoikilocytosis, and iron studies showing low serum ferritin, reduced transferrin saturation, and elevated TIBC. Management focuses on identifying and treating the underlying cause, alongside iron replacement therapy—usually oral iron, with intravenous formulations reserved for intolerance, malabsorption, or severe deficiency. Early recognition and appropriate treatment restore hemoglobin levels, replenish iron stores, and prevent long-term complications.

Questions and Answers:

What are the most common symptoms of iron deficiency anemia?

Iron deficiency anemia commonly presents with fatigue, dizziness, headaches, shortness of breath on exertion, cold intolerance, brittle hair, pale skin, dark under-eye circles, atrophic glossitis, angular stomatitis, and nail changes such as koilonychia. These symptoms result from reduced hemoglobin and impaired tissue oxygenation.

What causes iron deficiency anemia in adults?

In adults, iron deficiency anemia is most often due to chronic blood loss, particularly from heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer disease, colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or coeliac disease. Poor dietary intake, pregnancy, and malabsorption after gastric surgery are additional causes.

How is iron deficiency anemia diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on a microcytic hypochromic anemia on full blood count, a characteristic blood film showing pencil cells and anisopoikilocytosis, and iron studies demonstrating low ferritin, low transferrin saturation, and an elevated TIBC. Additional investigations, such as endoscopy or coeliac screening, may be required to identify the underlying cause.

What are pencil cells and why do they occur in iron deficiency anemia?

Pencil cells are elongated, hypochromic red blood cells commonly seen in iron deficiency anemia. They form due to defective hemoglobin synthesis and abnormal membrane stability caused by iron depletion, resulting in distorted red cell morphology on the blood smear.

Why is it important to investigate the cause of iron deficiency anemia?

Identifying the underlying cause is essential because iron deficiency anemia may indicate significant pathology, including gastrointestinal bleeding or colorectal cancer, particularly in older adults. Simply replacing iron is insufficient; the source of iron loss must be determined to prevent recurrence and ensure early detection of serious disease.

Can iron deficiency anemia be a sign of cancer?

Yes. In individuals over 50, iron deficiency anemia may be the first presenting sign of colorectal cancer. Unexplained iron deficiency always warrants thorough gastrointestinal evaluation, including OGD and colonoscopy, even in the absence of overt GI symptoms.

How is iron deficiency anemia treated?

Treatment includes correcting the underlying cause and replenishing iron stores. Oral iron therapy is first-line, usually with ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, or ferrous gluconate. Intravenous iron is used when oral iron is not tolerated, ineffective, or when rapid correction is required.

How long does it take to recover from iron deficiency anemia?

Hemoglobin levels typically begin to improve within 2–3 weeks of initiating treatment, but complete correction of anemia and restoration of iron stores may take 2–3 months. Treatment should continue for at least 3 months after hemoglobin normalises to fully replenish iron reserves.

What foods help improve iron deficiency anemia?

Iron-rich foods include red meat, liver, poultry, fish, legumes, leafy green vegetables, fortified cereals, nuts, and seeds. Vitamin C enhances iron absorption, whereas tea, coffee, and calcium-rich foods can inhibit absorption.

Can iron deficiency anemia cause hair loss and brittle nails?

Yes. Iron deficiency can impair keratin production, leading to hair thinning, brittle hair, spoon-shaped nails (koilonychia), and slow nail growth. Correcting iron levels often results in gradual improvement.

References:

Hillman R.S., Ault K.A., Rinder H.M., et al. (2011). Iron-Deficiency Anemia. In: Hillman R.S., Ault K.A., Rinder H.M., eds. Hematology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed., pp. 53–64. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Means R.T. Jr. (2012). Red Blood Cell Function and Disorders of Iron Metabolism. In: Nabel E.G., ed. ACP Medicine, Section 15, Chapter 21. BC Decker, Hamilton, Ontario.

Polk R.E., Healy D.P., Sahai J., et al. (1989). Effect of Ferrous Sulfate and Multivitamins with Zinc on Absorption of Ciprofloxacin in Normal Volunteers. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 33(11):1841–1844.

Camaschella C. (2015). Iron-Deficiency Anemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 372:1832–1843. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1401038.

Cleveland Clinic. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & Treatment. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17738-iron-deficiency-anemia

National Institutes of Health (NIH). Office of Dietary Supplements – Iron Fact Sheet. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/

American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Gastrointestinal Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Anemia. Available at: https://gastro.org

British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). Guidelines for the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Adults. Available at: https://www.bsg.org.uk

Keywords:

iron deficiency anemia, iron deficiency anaemia, IDA, low iron, low ferritin, ferritin test, transferrin saturation, microcytic hypochromic anemia, high RDW low MCV, anisopoikilocytosis, pencil cells, koilonychia, angular stomatitis, atrophic glossitis, iron deficiency anemia symptoms, iron deficiency anemia diagnosis, iron deficiency anemia treatment, oral iron therapy, oral iron supplements, IV iron therapy, intravenous iron indications, parenteral iron therapy, iron deficiency anemia guidelines, iron deficiency anemia management, iron deficiency anemia causes, gastrointestinal bleeding, menorrhagia iron deficiency, iron deficiency anemia colon cancer, iron deficiency anemia bowel cancer, iron deficiency anemia elderly, iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy, iron deficiency anemia in CKD, iron deficiency anemia in children, iron deficiency anemia diet, iron deficiency anemia foods, iron deficiency anemia lab results, ferritin low causes, iron absorption, iron deficiency malabsorption, coeliac disease iron deficiency, iron deficiency after gastric surgery, iron deficiency anemia cure, iron deficiency self management

This blog is a good read and the most fascinating thing is the way the topic is explained. I am going to recommend it to my peers and family.

Hi Manipal,

Thank you for your comment.

Pleased that you found this article helpful.

BW

Sir, Can you please tell which stain you used to stain the cells and also the type of microscope used and the magnification under which it was observed?